THE TRAGIC STORY OF HORACE WELLS

(1815 – 1848)

A Vermont native and son of affluent parents, Wells began studying dentistry in Boston in 1834. After a two-year apprenticeship (the first dental school did not open until 1840), he opened a practice in Hartford, Connecticut in 1836. By 1841 he had married, had a child, and built up a busy practice filled with respectable members of society, including the governor of Connecticut. In 1836, he wrote to his sister that his profits were “from about five to twenty dollars a day.” He was known as a dentist of ability, and invented and constructed many of his instruments. He also took on apprentices, one of whom was William T.G. Morton. In 1843 Morton joined Wells in the practice while Wells continued to instruct Morton.

In 1799, the English chemist Sir Humphry Davy had decided to experiment on himself by inhaling nitrous oxide. He learned first-hand the euphoria and dis-inhibition it caused and called it “laughing gas”. Forty-five years later, in 1844, Wells witnessed a demonstration by G. Q. Colton billed as “A Grand Exhibition of the Effects Produced by Inhaling Nitrous Oxide, Exhilarating, or Laughing Gas.” During the demonstration, a local apothecary shop clerk became so intoxicated by nitrous oxide that he did not react when he struck his legs against a wooden bench while jumping around, and was unable to recall his actions while under the influence.

The next day, Wells conceived the idea that a tooth might be extracted without pain if the patient was under the influence of nitrous oxide. Troubled by a decayed molar, he courageously conducted the trial on himself. Colton administered the gas to Wells, and an associate performed the extraction. According to Colton’s later account, “Wells clapped his hands and exclaimed, ‘It is the greatest discovery ever made. I did not feel so much as the prick of a pin.” Wells then proceeded to extract teeth from some fifteen patients over the following days.

Wells traveled to Boston, Massachusetts, in a fateful attempt to convince the medical and dental profession of the efficacy of nitrous oxide. Wells and Morton’s practice had dissolved in October 1844 (Wells thought Morton unqualified), but they remained on friendly terms. Morton was enrolled in Harvard Medical School at the time, and agreed to help Wells introduce his ideas, although Morton was skeptical about the use of nitrous oxide. While in Boston, Morton introduced Wells to several prominent physicians at Harvard, and it was decided that the demonstration was to take place following a lecture to the medical students by the eminent physician, John Collins Warren.

The date and place of Wells’ demonstration has historically been reported as occurring on January 20, 1845, in the surgical amphitheater of Massachusetts General Hospital. A recent, and more thorough, review of his activities in Boston during that time suggests that it happened around the end of January 1845, in a public hall on Washington Street, Boston. After a patient waiting for an amputation backed out, a medical student volunteered to have a tooth extracted under the gas. What followed has been the subject of some debate, and raises the possibility that the story that has been perpetuated over the years might not be entirely accurate.

Wells stated that his demonstration was conducted in the presence of a large number of students and several physicians, but no physicians who witnessed Wells’ demonstration have been identified. Apart from four descriptions by Wells and one by Morton, there are seven statements by five former medical students who were present when Wells addressed the medical students after Warren’s lecture. Descriptions of the patient’s response to the extraction of his tooth are fairly consistent. According to Wells, the patient experienced some pain, but later stated that the pain was “not as much as usually attends the operation.” Wells attributed the failure of complete insensibility to the fact that he had withdrawn the bag too soon. Some observers considered it a “humbug affair.” A similar description was provided by one of the students who witnessed the affair: “A tooth was extracted from one person, who halloed somewhat during the operation, but on his return to consciousness, said he felt no pain whatever.” Another student thought the patient did not appear to experience any pain, but some of the students believed it was an “imposition.” Wells’ friend and former partner, William T.G. Morton, was more dismissive: “Dr. Wells administered the gas, and extracted a tooth, but the patient screamed from pain, and the spectators laughed and hissed.”

However varied the reports, Wells evidently did not consider it the overwhelming success he had hoped for. Had he recognized the demonstration as a “partial success” (his own description), he might have performed a number of trials of nitrous oxide for painful procedures while he was in Boston – but he gave up after one unconvincing attempt and returned to Hartford the following day. He left, as Morton wrote, “…in great disgust, or disappointment.”

Two weeks later, in February 1845, Wells advertised his home for rent. By April, his dental practice in Hartford was declining and he practiced only sporadically until November 1845. He became ill shortly after the failed demonstration with non-specific symptoms that evaded diagnosis.

Following the public notice of Morton’s successful demonstration of surgery under anesthesia in October 1846, Wells, on December 7, 1846 , addressed a letter to the editor of the Hartford Daily Courant, outlining his experiments and experience with anesthesia and stating that he had met with Morton and Jackson while in Boston “both of whom admitted it to be entirely new to them. Dr. Jackson expressed much surprise that severe operations could be performed without pain, and these are the individuals who claim to be the inventors.” Wells’ letter also states he had preferred nitrous oxide over sulphuric ether for his experiments as being a potentially less harmful substance.

(it doesn’t really seem such a crazy idea today)

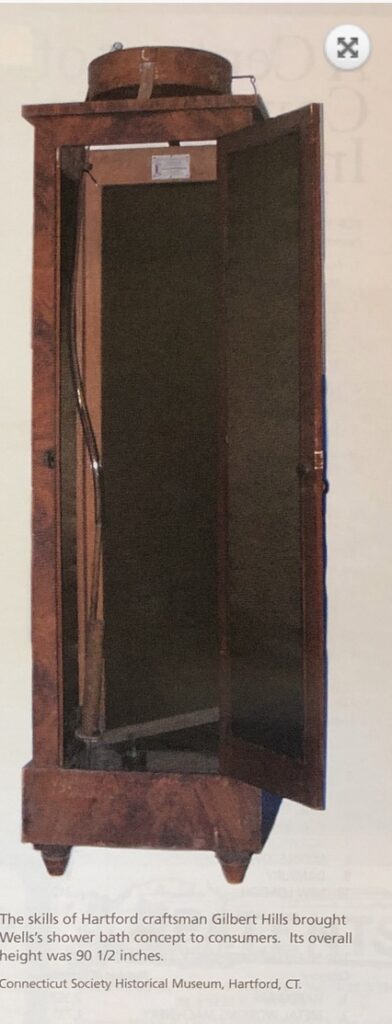

Wells continued to seek public and official recognition, largely unsuccessfully, for the discovery of anesthesia. He patented a shower bath in 1846 (see above) and tried to market it. He also planned to sail to Paris to purchase paintings to resell in the United States. When he traveled to Paris in early 1847, he petitioned the Academie Royale de Medicine and the “Parisian Medical Society” for recognition in the discovery of anesthesia.

Wells moved to New York City in January 1848, leaving his wife and young son behind in Hartford. He lived alone in Lower Manhattan and began self-experimenting with ether and chloroform, and became addicted to chloroform. The effects of sniffing chloroform and ether were unknown. In January 1848, in New York City, he rushed into the street and threw sulfuric acid over the clothing of two prostitutes while he was under the influence of chloroform. He was arrested (possibly on January 21, his 33rd birthday), and committed to New York’s notorious prison known as “The Tombs.” As the influence of the drug waned, his mind started to clear and he realized what he had done. He asked the guards to escort him to his house to pick up his shaving kit. He committed suicide in his cell on January 24, slitting his left femoral artery with a razor after inhaling an analgesic dose of chloroform.

Wells’ chloroform-assisted suicide occurred a few days before the death of 15 year old Hannah Greener of Newcastle in the United Kingdom, regarded as the first death under chloroform anesthesia. Hannah died on January 28, 1848, after receiving a chloroform anesthetic for the removal of a toenail. She was a healthy 15-yr-old girl who had successfully undergone an anesthetic with diethyl ether several months before for the removal of another toenail. Hers was the first death attributed to the new and wondrous blessing of anesthesia for surgical pain relief. Various authors have ascribed her death to an anesthetic overdose, aspiration of the water and brandy used in attempts to resuscitate her, or some combination of secondary complications that will never be determined.

In a sad twist of fate, Wells died unaware that a few weeks earlier the “Parisian Medical Society” had recognized him as the inventor of anesthesia, and made him an honorary member. Christopher Starr Brewster, an American dentist living in Paris, France, wrote to Wells on January 12, 1848 with this news, but no record of this award or the diploma have been found. Wells’ exhilaration in his discovery lasted approximately 6 weeks, and the next 3 years were characterized by numerous misfortunes and failures that ended with his untimely death.

He is buried at Cedar Hill Cemetery in Hartford, Connecticut.