PAIN CONTROL IN THE “OLDEN DAYS“

Ever since civilization began, no one having any type of surgical or dental procedure wants to feel pain. In classical antiquity, the Greek Galen Dioscorides attributed anesthetic faculties to poles made of mandragon and wine. In later times, some even experimented with hypnotism. In China and India they used marijuana and hashish, while opium was widely used in different parts of the world, as was alcohol. In South America, ancient groups of Peruvian Indians chewed coke and drank alcohol with fermented corn. Despite everything, the pain relief was far from satisfactory, so surgeons and dentists worked as quickly as they could; in fact, they were described according to their agility. Many patients chose to live with tumors, or rotting teeth rather than undergo surgery or a tooth extraction. In the early 19th century there was an enabling environment for the development of anesthesia. On the one hand, chemistry, biology and physiology offered new findings every day. On the other hand, doctors and surgeons of the new generations were more sensitive to the suffering of the sick.

Although ether was discovered in 1275 by a Spanish chemist, it wasn’t until 1841 that the anesthetic property of ether was put to work. In 1839, Dr. Crawford Williamson Long was a new graduate the University of Pennsylvania medical school. While there, he had witnessed (and participated in) “ether frolics”, public gatherings of those who would take ether for amusement, and noted the lack of pain felt by those getting injured at these events. Long became intrigued with its possible use in surgery. After graduation, he returned to his hometown of Jefferson, Georgia. During an “ether party”, he became acquainted with a local student named James Venable. Venable confessed that he wanted two small tumors on his neck removed, but kept postponing the procedure from fear of pain. On March 30, 1842 Long, using ethyl ether as an anesthetic, successfully removed one of the two tumors. Venable felt no pain from the procedure and paid two dollars for the tumor extraction. This was the first surgical operation performed on an anesthetized patient.

Long used his technique successfully in other patients but, delayed in publicizing his experiences due to the few opportunities he had had to employ ether anesthesia in his practice and a belief that, following the second Venable operation, the anesthetic state would not last long enough to be used in capital procedures. Seven years later, in December 1849, he published his results in the Southern Medical and Surgical Journal. The article included the authentication of the account by Venable, two witnesses to the procedure, and a mention of another operation performed under ether anesthesia on July 3, 1843.

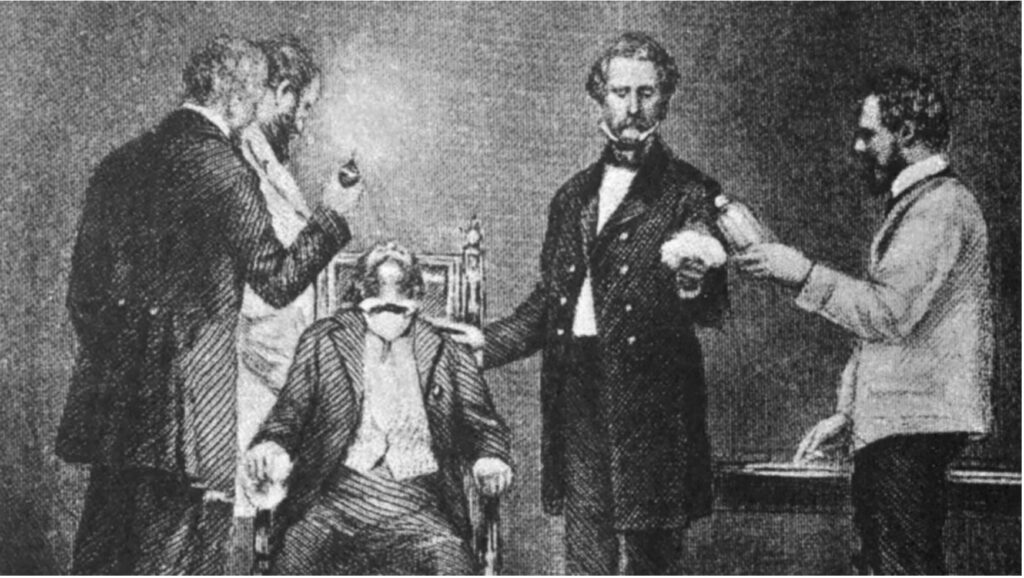

Unfortunately for Long, his delay in publishing was costly – it came too late. Three years previously, on October 16, 1846, another physician had already successfully demonstrated the use of ether as an anesthetic. And so it was that the name commonly attached to the first general anesthetic is that of the self-trained dental surgeon, William T.G. Morton.

Almost 180 years later, Morton’s name is still synonymous with ether, but there were still two other contenders who predated him. Each had experimented with the use of general anesthesia: the dentist Horace Wells, and chemist Charles T. Jackson. Morton had been a student of both men, and capitalized on Wells’ failures and Jackson’s successes to claim the crown. The main players in the Great Ether Controversy were Morton and Jackson, but the end result would exact a tragic toll on all three.