KING GEORGE II DIES ON THE TOILET FROM A DISSECTION – AND GETS DISSECTED

As has been described numerous times, on the morning of October 25, 1760, the King arose from bed, had a cup of hot chocolate, and went alone to his privy for a bowel movement. His valet heard a loud crash and found him unresponsive on the floor, his only sign of trauma being a cut on his face presumably related to his fall. The house surgeon, Mr. Andrews, was immediately brought in and as might be expected, was unable to revive the King despite multiple attempts at bloodletting. As it was apparent that the King had died, and as was the custom, an autopsy was ordered to rule out any nefarious cause of death. To this end, Dr. Nicholls was directed to perform the autopsy and embalming the following day.

While Osler’s quote “There is no disease more conducive to clinical humility than aneurysms of the aorta” is well documented and often included in treatises on aortic disease, perhaps the second most common reference is the notation that King George II died of an acute aortic dissection. The origin of this association derives from the official autopsy performed by Dr. Frank Nicholls, and while Dr. Nicholls describes the postmortem findings in detail, the attribution of the cause of death may have been incorrect.

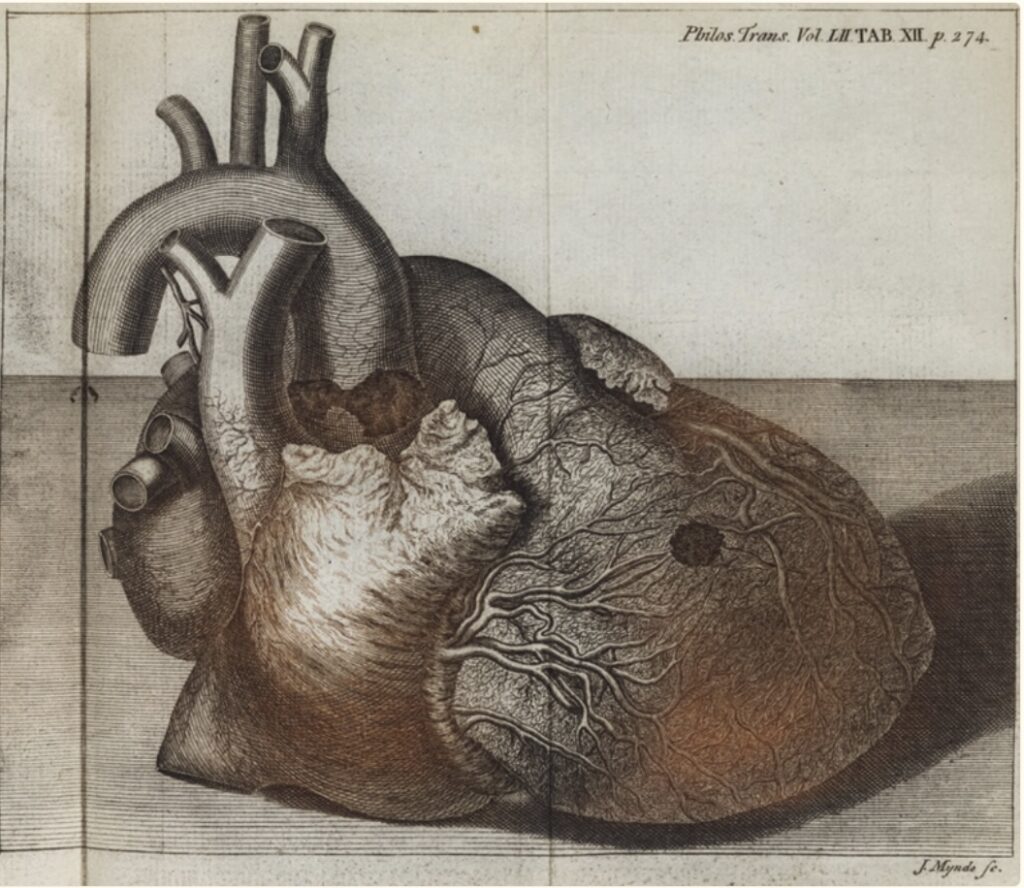

The abdomen was opened first, with no abnormalities noted with the exception “… some hydatides (or watery bladders) were found between the substance of each kidney, and its internal coat.” Upon opening the chest, hemopericardium was discovered, the blood coagulated, “… nearly sufficient to fill a pint cup … upon removing this blood, a round orifice appeared in the middle of the upper side of the right ventricle of the heart, large enough to admit the extremity of the little finger” Dr. Nicholls also noticed that while intact, the aorta, pulmonary artery, and right ventricle were “… stretched beyond their natural state.” Dr. Nicholls rightly surmised that the proximal cause of death was cardiac tamponade and that the King “… must, therefore, have dropped down, and died instantaneously.” Upon opening the aorta, an approximately 4-cm long “transverse fissure on its inner side” was identified, “through which some blood had recently passed.”

description of the autopsy findings of King George II.

As opposed to the lore that King George II died of aortic dissection that ruptured into the pericardial sac, Dr. Nicholls clearly described right ventricular rupture with aortic dissection “… as the immediate cause of … bursting.” Importantly, Dr. Nicholls did not note the aorta to have ruptured, the right ventricle ruptured. While acknowledging that the King did have a Stanford Type A aortic dissection, from the autopsy report, the possibility arises that his demise was due to coronary artery disease.

King George II had been having cardiac symptoms for some time with Dr. Nicholls noting in his report that “… his Majesty had, for some years, complained of frequent distresses and sinkings about the region of the heart … his pulse was, of late years, observed to fall very much upon bleeding.” Angina would not be described by Heberden until 1768 (and published in 1772) and the relationship of angina to coronary artery disease would have to wait another 140 years. Thus, this etiology was not available to Dr. Nicholls to aid in his diagnosis. Postinfarction myocardial rupture is well described albeit less common in the present era due to early intervention and is even less common on the right side of the heart. The presence and etiology of coronary artery disease in King George II is unknown and may have been secondary to atherosclerotic disease or may have been due to the chronic dissection itself. While acute ischemia secondary to aortic dissection is typically due to occlusion or disruption of the ostia of the coronaries, dissection of one or both coronaries can lead to chronic ischemia. One bit of evidence to support the coronary artery disease hypothesis is the illustration by Dr. Nicholls which suggests the perforation to have occurred in a watershed zone on the free wall of the right ventricle.

Were it not for Dr. Frank Nicholls’ precise and detailed autopsy notes from 264 years ago, it would have been impossible to revisit the the cause of death of King George II in the light of our current understanding of pathophysiology. (Documentation, documentation, documentation….!)

Much of the above was taken verbatim from the article “Revisiting the Death and Autopsy of King George II”, by Yota Suzuki, MD and Abe DeAnda, Jr., MD. Aorta (Stamford), 2021 Oct; 9(5): 196–198.