A SUPERB COLLECTION OF MEDICAL AND HISTORICAL ITEMS

BELONGING TO CIVIL WAR PHYSICIAN BLENCOWE EARDLEY FRYER, M.D. (1837 – 1911)

RARE APOTHECARY-STYLE MEDICINE CHEST c. 1855

MADE BY NATHAN STARKEY OF PHILADELPHIA

USED BY DR. FRYER DURING AND AFTER THE CIVIL WAR

SEVEN MILITARY COMMISSIONS UP TO THE RANK OF RETIRED COLONEL,

SIGNED BY FIVE PRESIDENTS, INCLUDING ABRAHAM LINCOLN

FRYER’S MEDICINE CHEST – MADE BY NATHAN STARKEY OF PHILADELPHIA

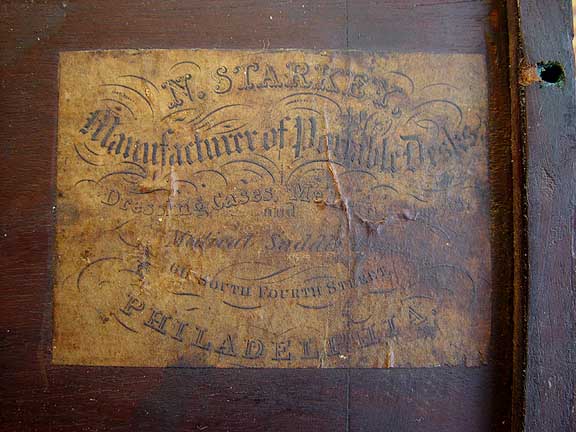

This medicine chest has a partial makers label, indicating it was made by Nathan Starkey of Philadelphia, thought to be the only maker of quality medicine chests in the United States. Fortunately, the label is intact enough to reveal Starkey’s address on Fourth Street in Philadelphia. According to Edmonson, he was active from 1831 – 1865; however, he was only at the 66 Fourth Street address from 1843- 1855.

There are probably less than ten of these chests still in existence.

The quality of the chest is superb. It is made of solid mahogany, and the top handle and door escutcheons are inset with brass, although one of the escutcheons is unfortunately missing. All of the items were purchased from a descendant of Fryer, and the chest retains many of its original contents: medicine bottles (with original contents), a set of apothecary scales, several sets of apothecary weights, individual medications/powders, a small container of blank paper envelopes (for prescriptions) , and three blank prescription papers from the U.S. Army Post Hospital at Fort Leavenworth, Kansas, dating from the 1870’s. The chest was evidently loaned for display at one time in the past, judging from the typed display card and the inventory markings on each item.

NATHAN STARKEY, MASTER CABINETMAKER 1807 – 1864

Nathan Starkey was born in Burlington county, New Jersey in 1807. His apprenticeship years are a mystery, but he was obviously a very talented craftsman. Edmonson shows him active beginning in 1831, when he was living in Philadelphia and manufacturing “Portable Desks, Dressing cases, Medicine Chests, & Ladies Work Boxes.” He moved to no less than seven different Philadelphia addresses from 1831 and 1865.

On his website antiquescientifica.com, the renowned collector and dealer Alex Peck states:

“To my knowledge, Starkey is the only identified maker of quality medicine chests in the United States.”

Examples of Starkey’s work are extant, but scarce. In 1955, six examples of his portable desks were recorded; a subsequent survey done in 2005 turned up two more known examples: one was in private hands, the other had belonged to Andrew Jackson’s private secretary and was reputed to have been used during treaty negotiations with Mexico – however its whereabouts was unknown.

My own limited research has uncovered three other examples of Starkey-labelled medicine chests, all identical to the one shown here. In the October 2005 edition of the magazine Antiques, Eleanor H. Gustafson writes:

“Stylistically, the earliest example of Starkey’s work illustrated here is the portable medicine chest of about 1845… which retains many of its original bottles as well as the original mortar, pestle, scale, and weights. It has two locks, so that it could be locked on the inside as well as on the outside. A release on the inside unlocks a sliding panel to a secret compartment, where poisons would have been stored…”

Clearly, that is an excellent description of the chest shown here, sans mortar and pestle.

She closes the article with this comment:

“Although Starkey worked in relative obscurity as compared to many of his Philadelphia contemporaries, the few remaining objects by him exemplify not only his craftsmanship but his design expertise. His long tenure in the city’s trade was a testament to his craft as well as his ability to use contrasting woods, inlays, fancy accessories, and ingenious construction techniques to meet ever-changing fashion and taste for more than thirty years.”

DR. BLENCOWE EARDLEY FRYER

Blencowe Eardley Fryer was born in Somerset, England on October 26, 1837. His father died at an early age, and when he was 7 years of age, his widowed mother and five siblings emigrated to the U.S. and settled in Philadelphia. He received his medical degree at the University of Pennsylvania in 1859, and for nearly two years he was resident physician and surgeon of the Episcopal Hospital, in Philadelphia. On May 28, 1861, he was commissioned an Assistant Surgeon in the U.S. Army, with the rank of First Lieutenant. From that date until 1887, he remained in the service of the Army, and successively passed through the ranks to Lieutenant-Colonel in 1891, achieving the rank of colonel upon his retirement from the Army in 1901.

During the Civil War, he did general field and hospital duty as a surgeon until 1863, when he was made Surgeon-in-charge of Brown Hospital in Louisville, Kentucky, that being one of the largest institutions of its kind during the war. He remained at this post until the end of the war. He received brevet commissions, Captain and Major, March 1865, for faithful and meritorious services during the war. After the close of the war, he was six months Acting Medical Director of the Ohio, with headquarters at Detroit Michigan. On May 28, 1866, he was commissioned Assistant Surgeon, with the rank of Major. In August,1867, he was assigned to the position of Post Surgeon, at Fort Harker, Kansas, remaining there until May, 1872. After one year in New Mexico, he was appointed a member of the Army Medical Examining Board, with headquarters in New York City, where he remained until 1877, when he was assigned to duty at Fort Leavenworth. He made a special study of diseases of the eye and ear, having as preceptor Prof. H. Knapp, formerly of Heidelburg, Germany, then New York, one of the most skillful oculists and aurists in the world. Dr. Fryer assumed the chair of Professor of Diseases of the Eye and Ear, in the Kansas City Medical College. He served as President of the Kansas State Medical Society in 1881.

Dr. Fryer had extensive experience during the Civil War – he contributed no less than 14 case studies to the Medical and Surgical History of the War of the Rebellion. An example of one is this, shortly after the Battle of Bull Run:

CASE 1044.–“A Sergeant of Rickett’s Battery walked from the field to the hospital after having been struck by a round shot, en ricochet, on the arm, fracturing the humerus in three places and producing great contusion without breaking the skin. The case is interesting from two facts–the great injury to the bone without laceration of the surrounding soft parts, and from the fact that disorganization of the tissues did not take place in this, as it nearly always does in all parallel cases. The result of the treatment of this man was doubtful, and the question of amputation was raised by the other medical officers of the hospital, but I strenuously opposed it, and had the satisfaction of seeing this useful soldier recover and return to duty with no other deformity than a slight shortening, and with a perfect use of the arm. The treatment in this case was to lay the arm on a pillow; cold water until all swelling had subsided, after which I ordered a plaster of Paris splint.” He also made contributions to the Army Medical Museum, although the circumstances surrounding his contribution would be considered unethical by today’s standards, as is evident from the following story…

While Dr. Fryer was the Post Surgeon at Fort Harker, he was involved in a local tragedy that occurred in late January or in very early February 1869 – known as the Mulberry Creek Massacre ( Ellsworth County, Kansas ). There are a few versions of this tragic story. Apparently a group of about twenty Pawnees were returning home to their Reservation in Nebraska. A few of these men had served recently as U.S. Army scouts and had discharge papers in hand. Their presence alarmed local settlers, who summoned the cavalry. Though the Pawnees argued they were ex-Army scouts and tried to show their papers, a gunfight broke out near Mulberry Creek. Seven Pawnee were killed instantly ( by U.S. Army soldiers and a few settlers ) and five more were wounded and left to die on the hard winter ground. One Pawnee was taken prisoner. Pawnee Chiefs were infuriated by the murders but did not retaliate. The Pawnee Chiefs applied to civil and military authorities to rectify the situation but the pleas fell on deaf ears.

Shortly after the massacre, Dr. Fryer dispatched a civilian to the massacre site to collect the skulls of the dead Pawnee. After he had found and decapitated one corpse, a blizzard set in, and the Pawnee survivors stopped him from collecting the others skulls. But two weeks later, the weather moderated and Fryer resumed his search, locating the bodies of five Pawnees. Acting upon orders from the Surgeon General’s Office in Washington, D. C., Fryer removed their heads for scientific research. After boiling the heads and preparing them for study, he sent the five additional crania to the Army Medical Museum for further analysis. The Pawnee skulls became part of a shipment of 26 sent to the Museum, including skulls from the Cheyenne, Caddo, Wichita, and Osage tribes. Not until 1995 were the skulls returned to the Pawnee tribe and buried with full military honors at Genoa City Cemetery in Nebraska.

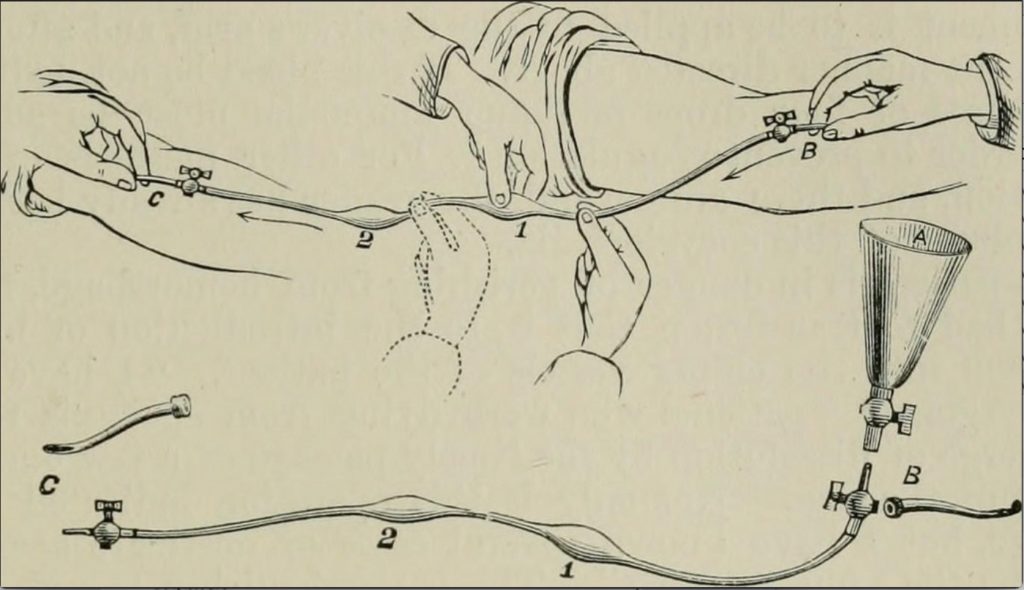

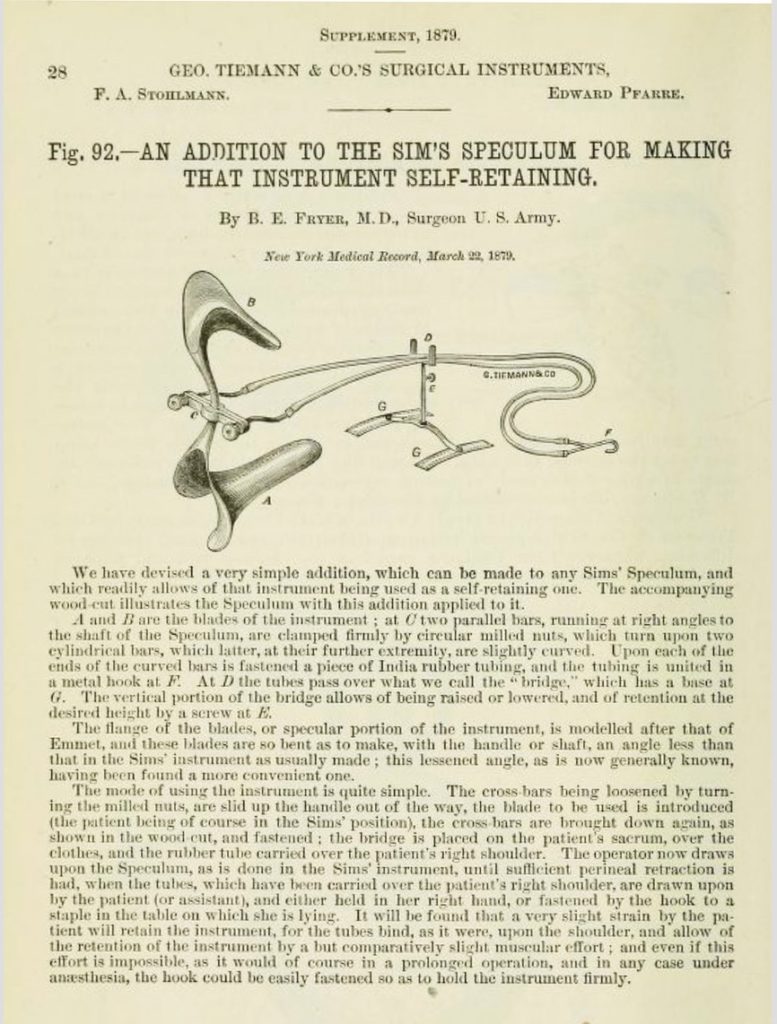

Fryer also designed a modified transfusion apparatus, as well as a modified Sims speculum. Both of these items were sold by George Tiemann of New York in his 1879 catalog:

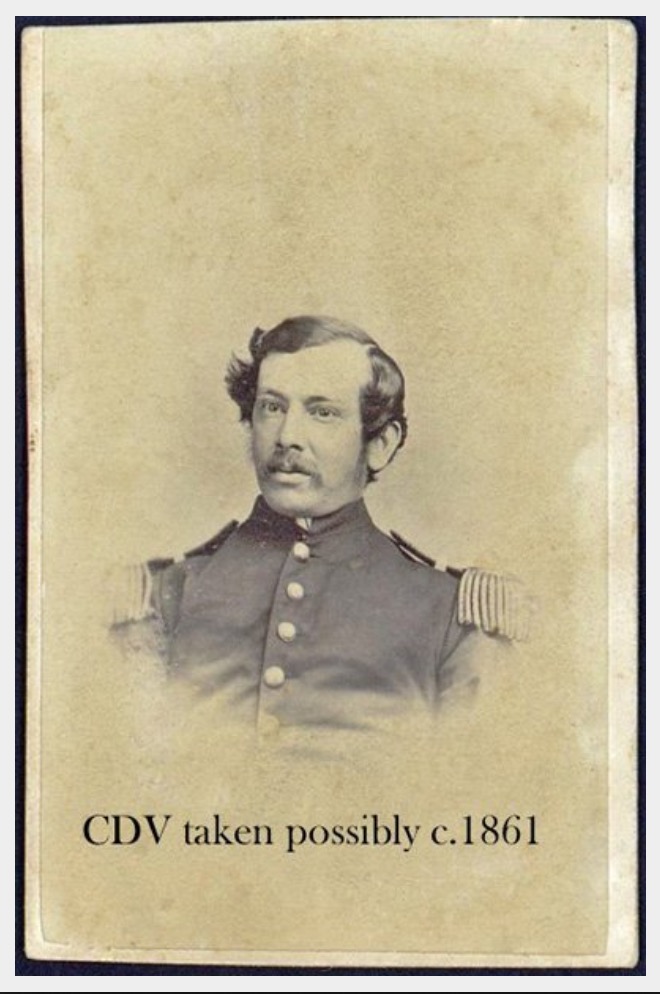

PHOTOS OF DR. FRYER

DR. FRYER’S SEVEN MILITARY COMMISSIONS, ONE SIGNED BY ABRAHAM LINCOLN

The commissions span the years 1861 to 1910. They begin with his commission as an Assistant Surgeon in 1861, bearing the faded (but certainly legible) signature of President Abraham Lincoln. This is followed by two commissions signed by (then-Vice President) Andrew Johnson (signatures are rubber-stamped, not actually handwritten), one in 1866 appointing him a Major, and one in 1868 appointing him Surgeon – the signatures on both appear to be stamped. In 1904, President Benjamin Harrison signed a commission appointing him “Assistant Medical Purveyor with the rank of Lieutenant Colonel”. President Theodore Roosevelt signed a commission in 1904, appointing him a “retired Colonel” and in 1910, President William Howard Taft followed suit, appointing him a “Colonel on the retired list of the Army.”

All except Lincoln’s bear the official War Office seal.