VERY RARE HOSPITAL MENU DATED CHRISTMAS 1864

FOR MC CLELLAN U.S. ARMY GENERAL HOSPITAL IN PHILADELPHIA

MC CLELLAN ARMY GENERAL HOSPITAL

There surely cannot be many of these in existence – a menu for the Christmas dinner held in 1864 at Mc Clellan U.S. Army Hospital in Philadelphia. No doubt, someone at the dinner kept this as a souvenir of the evening’s festivities, perhaps to share with family back home what the holiday fare was for the evening.

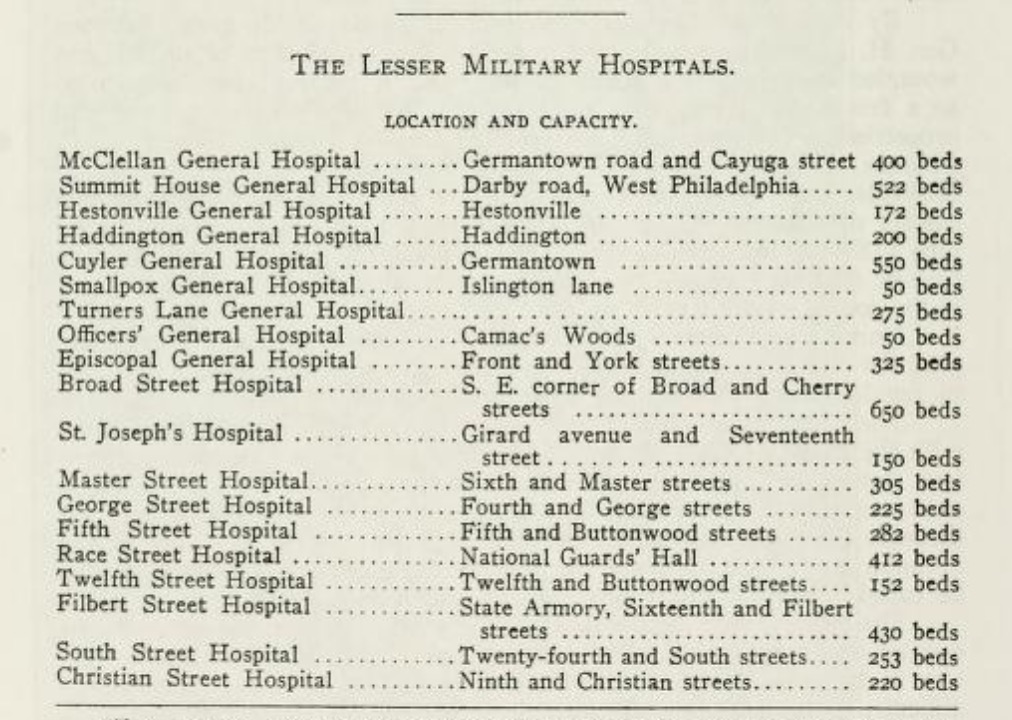

Mc Clellan Army General Hospital was a 400 bed hospital established in February 1863 at Germantown Avenue and Cayuga Street, in an area of North Philadelphia known as “Nicetown”. The town name of Nicetown was named for a family of early settlers with the last name of “Neiss,” which got shortened and Americanized to “Nice.” Originally, the area consisted mostly of rural farmland, which served as a passage between Germantown and Philadelphia. By 1854, the area had moved within the Philadelphia city limits.

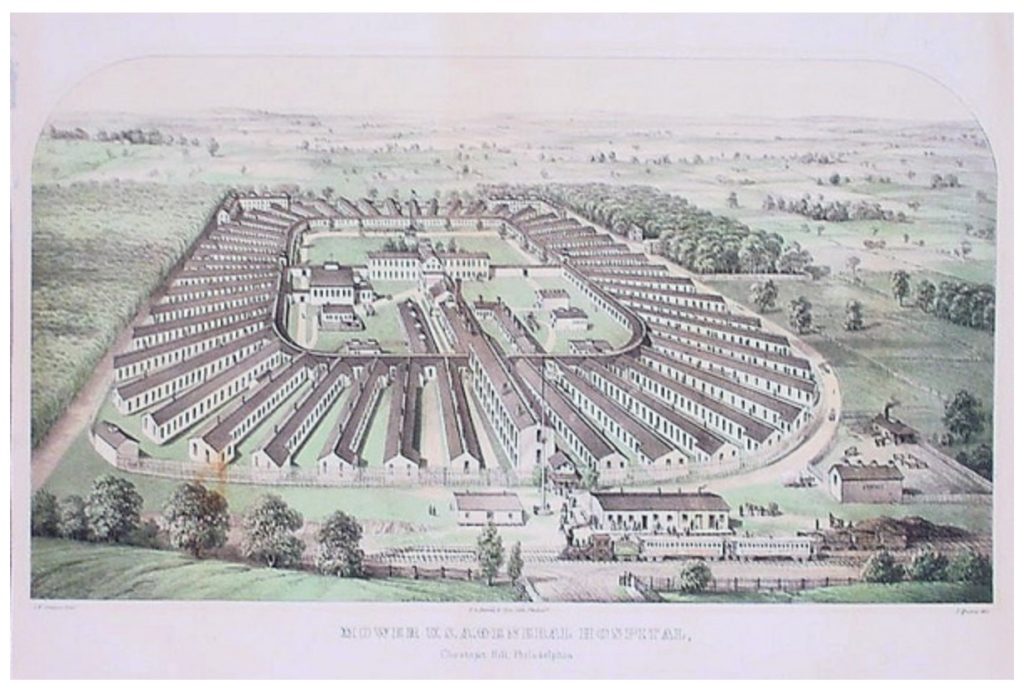

Mc Clellan was the last general hospital established in Philadelphia during the war. It was arranged upon the general plan of the Mower (or Chestnut Hill) Hospital, another Philadelphia general hospital, which was completed in January 1863. The blueprint was that of an elliptical corridor, from which 18 wards radiated, the office building being in the center:

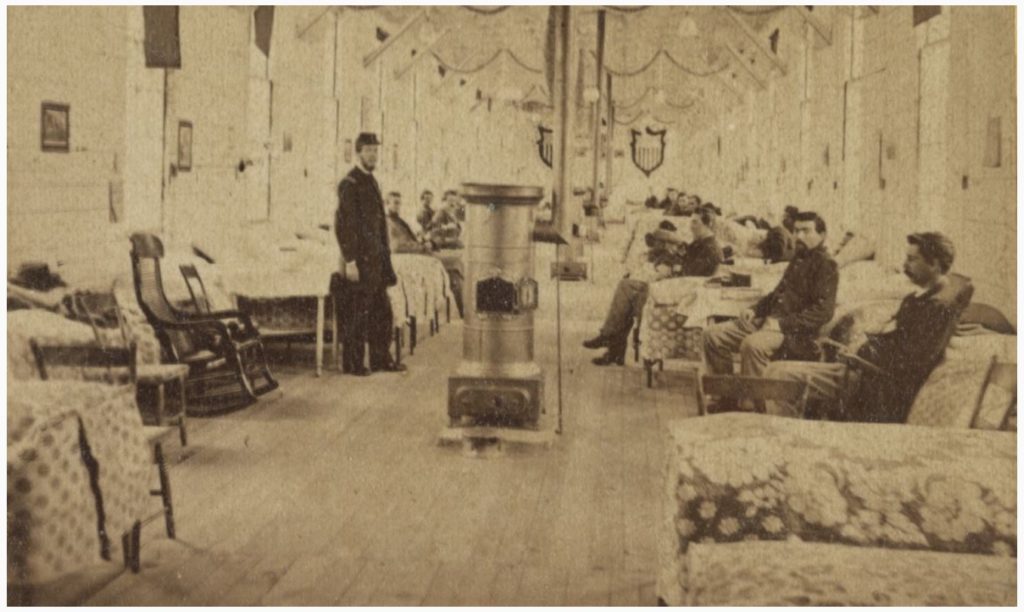

This well-known stereographic image was made of Ward 14 at Mc Clellan General Hospital circa 1863. It is attributed to John Moran, who worked at M.S. Hagaman’s photographic studio on Arch Street in Philadelphia. It depicts two rows of recovering soldiers seated next to their beds line both sides of the ward. The decorations are abundant – streamers, flags, lace bedspreads, flowers, framed pictures, and patriotic statements of affirmation are painted on the walls. Note the row of heaters down the middle of the floor, and the large windows on the right side to ensure adequate ventilation and light.

In his book “Philadelphia in the Civil War” (published in 1913), Frank H. Taylor states that the officials most associated with the “Mc Clellan” were: Surgeon in Charge, Lewis Taylor; executive officer and A.A. Surgeon J. P. Murphy; asst. executive officer Capt. T.C. Kendall of the Invalid Corps; asst. surgeons Isaac Morris, Jr., Levi Curtis, H.C. Primrose, W.L. Wells, H.B. Buehler and Richard A. Cleeman.

PHILADELPHIA HOSPITALS IN THE CIVIL WAR

We are often reminded that during the Civil War, more soldiers died of disease than wounds. While this may be true for the overall number, it did not hold true for certain states. In his book “Philadelphia in the Civil War” (published in 1913), Frank H. Taylor) states the following:

“Pennsylvania was one of four of the loyal states among whose soldiers of the Civil War the fatalities of battle

exceeded those caused by disease. The Pennsylvania troops lost from

battle casualties 56%, and from disease 44%, of all deaths during the

war.”

However, the percentage of deaths from sickness relative to total enlistments was the lowest in Pennsylvania, compared to the other states in the Union. This fact was attributed to the geographical location of Philadelphia, which was able to receive wounded men of Pennsylvania regiments by water transport from the battlefields of Virginia, as well as by rail from inland locations. The government decided to create several army hospitals in Philadelphia to care for the sick and wounded, regardless of their statehood. Initially, there were 24 large and small hospitals in the city, in most cases using existing buildings adapted to the purpose. After West Philadelphia (also known as Saterlee) Hospital opened in June, 1862, followed by Mower (or Chestnut Hill). Hospital in January 1863, that number was reduced. By April 1864, there were 13 large general hospitals in the city. The “high tide” of hospital untilization came with the battle of Gettysburg. By July 5, 1863, the 5,000 previously empty hospital beds were filled; over the course of the next week, a flood of battle-torn humanity rolled into the city and dumped 10,000 more suffering wounded into the hands of the surgeons and nurses.

THE HOSPITAL SYSTEM IN THE CIVIL WAR

From the beginning, the Civil War created a demand for hospitals that neither the North nor the South could meet. Medical staff were not prepared for the devastation the new Minie ball and rifled cannon would inflict; the centuries-old tactic of lining up soldiers a few dozen yards apart to shoot at one another proved catastrophic. Bones were shattered and tissue shredded in ways physicians had never seen before.

In July of 1861, the first major battle occurred at Manassas, Virginia. Two unproven green armies met and effectively slaughtered each other. The North suffered 2,700 casualties, the South 1,900. As there was no organized ambulance system to remove the wounded or an organized medical treatment system to treat the wounded, injured soldiers lay as long as three days on the battlefield. By the fall of 1862, the casualties was staggering, numbering in the tens of thousands after major battles like Shiloh and Antietam. The need for space to treat the wounded was crushing, and medical staff resorted to setting up temporary hospital spaces wherever there was room – using churches, hotels, barns, farmhouses, tobacco warehouses, even the rotunda and of the U.S. Capitol.

In an extraordinary example of the “right person at the right time”, Dr. William Hammond was appointed surgeon general of the Union Army in April 1862. His innovations, along with the assistance of his brilliant medical director Jonathan Letterman, M.D., were responsible for creating a highly effective ambulance and hospital system. It was so effective it remained the standard delivery system for care of the wounded through World War II. The crux of the system lay in placing specialized personnel in outfitted mobile (Ambulance Corps), field, brigade, general, specialty and rehabilitation hospitals.

In an age many consider to be medically archaic, professionals and epidemiologists were making connections between good ventilation, cleanliness, and health. Hammond was instrumental in setting forth the basic principles of sanitation in 1863. Water, preferably both hot and cold, was needed for drinking, bathing, and wound care, but it was also vital for collecting and disposing of bodily wastes. He recommended one bathtub for every 26 patients, one water-closet (or toilet) for every 10, and one wash basin for every 10. Ventilation of the toilet area was deemed vital, and, if water was available, it was to be used to carry off fecal material immediately. Eventually, Hammond hired some of the leading physicians of the time as Medical Inspector Generals, to visit each and every hospital to ensure that these new standards of care and sanitation were being met.

As the war went on, it became clear that more permanent hospital spaces were essential, and the surgeons general for both governments soon determined that the pavilion-style hospital — already in use throughout Europe — was the best. This design featured long narrow wards or units that incorporated multiple windows located in opposing pairs for cross-ventilation. Additional features included heating sources, bed placement, window size and placement, and allotted space per patient, in cubic feet. The first pavilion-style hospital constructed during the war was the Confederacy’s Chimborazo Hospital in Richmond. Built in October 1861, it included 150 pavilions and 4,000 beds. It would remain the South’s largest hospital during the war.

In the North, West Philadelphia U.S. General Hospital (better known as Satterlee) opened in June 1862—a pet project of Hammond’s. It had 36 pavilions containing more than 3,500 beds, and 150 other tents were placed around the buildings in event of an emergency or nearby engagement. By the end of 1863, well-ventilated pavilion-style hospitals were erected in major cities of the North, accommodating up to 3,000 patients each. Letterman’s Ambulance Corps was functioning effectively, removing the wounded in a timely fashion from the battlefields. Tent hospitals were set up by the hundreds, and utilized at places like Gettysburg and City Point, a way-station. By war’s end, there were 204 general hospitals with over 135,000 beds. The book “Philadelphia in the Civil War” (published in 1913 by Frank H. Taylor) states the following:

“In the course of the Civil War the military hospitals of the North ministered to 6,454,834 cases of illness and wounds. Of these 195,657 were fatal… 157,000 soldiers and sailors were cared for in the general hospitals of Philadelphia during the war.”

Copyright © 2019 Medical and Surgical Collectibles | Powered by Astra