U.S. ARMY HOSPITAL DEPARTMENT CONTRACT SET

The type of set shown above may have been issued to a regimental surgeon, since post-mortem examinations were standard and required, as will be explained in more detail below.

It is missing one knife and the rachitome, and the brass plate has been removed. It is not unusual for the brass plates to be missing on military sets as these sets were sold as surplus after the Civil War and the buyers often removed the military markings.

New York City directories show that Hermann Hernstein began his business in 1846. Briefly located at 3 Chambers St., he moved to 7 Hague St. until 1851, when he moved to 68 Duane St. in 1854 he moved to 81 Duane, then in 1856 to 81 Duane and 393 Broadway. In 1857 he was located at 131 Mercer and 393 Broadway. His son Albert L. Hernstein joined the firm in 1861, after which it was known as Hernstein & Son. Some time after May 1, 1862 they relocated to 393 Broadway. They remained here for the duration of the Civil War, until some time after May 1, 1865 when they moved to 2 Liberty and 393 Broadway.

During the Civil War, Hernstein & Son produced and sold contract-ordered surgical sets from

the 393 Broadway address.

(*See the last section for information on the post-Civil War addresses of the company.)

The key to dating the set is that Hernstein & Son were only at the 393 Broadway address from the latter half of 1862 – first half of 1865, eclipsing the Civil War years. They were selling directly to the military at that time under contract. This set has a military latch, a feature not seen on civilian sets. The removable partition between the upper and lower layers has the logo of the firm during the Civil War: a spread eagle with a shield on its breast, a banner above with “H. HERNSTEIN” , and the eagle’s talons holding ribbons with “393 B’WAY” and “NEW YORK”. This patriotic design is seen in most of Hernstein’s military issued sets.

HERMANN HERNSTEIN

(1810 – 1883)

Typical of so many instrument makers of the time, Hermann Hernstein was born in Germany, and apprenticed to an instrument maker. He married Friedericke Speyer and after the birth of the first two of six children, departed Prussia in 1841, arriving in Philadelphia. Two months later, the family returned to Prussia, possibly due to his father’s illness. They returned to America in 1843, arriving in New York. He appears in the 1843 New York City directory, along with his business “H. Hernstein & Co.” at 3 Chambers St. Over the next five years he moves to two other locations, the last being 7 Hague. For some reason, he is not in the city directories for a period of two years, from 1849 – 51. Nevertheless, he is residing in his home in New York City when the 1850 Federal census is taken.

Hernstein continued to expand his business, which necessitated moving to various locations up until 1861. When the Civil War broke out, the demand for surgical instruments and medical supplies skyrocketed. His competitor was George Tiemann, the premier surgical instrument manufacturer in the city. As the battles continued, the sheer volume of wounded soldiers was more than enough to keep both firms in business. Both Tiemann and Hernstein won lucrative contracts with the U.S. Army Hospital Department, due to their capability for large-scale production. Other prominent manufacturers in Philadelphia, such as Kern and Kolbe, also won contracts and helped produce the requisite number of materiel. And as with so many other businesses, the calamity of the Civil War made them wealthy.

Hermann and Friedricke had six children. 4 daughters and two sons. Their eldest son, Albert Louis, was born in 1840, in Westphalen, Prussia. The other son, William Henry, was born 1852 in New York. Each son would continue in their father’s occupation of surgical instrument manufacture, but did not partner with one another. After the Civil War ended, Albert remained in New York City and assumed control of their father’s business. The company was now known as A. L. Hernstein and was in operation from 1865 – 1897.

William ventured west to St. Louis, Missouri, and joined with Albert S. Aloe to become Aloe & Hernstein. In 1876, William is listed as a principal in the firm. William’s brother-in-law, David Prince, worked as a salesman for the company. The partnership dissolved in 1885, and Aloe established A. S. Aloe & Company. That same year, Hernstein joined with Prince to form “Hernstein & Prince”, which was located across the street from their former employer. The business was apparently short lived, and is not listed in the 1889 directory. By 1891 William Hernstein had returned to A. S. Aloe & Company where he was employed as a clerk and manager until 1898.

Albert and William were both successful (to varying degrees), but neither lived to enjoy a lengthy retirement. Albert died at age 60 in 1900, after suffering with “angina pectoris” for four days. William died age 58 in 1908.

POST-MORTEM

The term means literally, “after death”. It can be used as an adjective (i.e. “post-mortem changes in color”), or as a noun (“She conducted a post-mortem examination”). It can be spelled as one word, or as two (with or without hyphen). For the purposes of this site, it will be used as a synonym for “autopsy”. An autopsy is a thorough external and internal surgical examination of a corpse to determine the cause, mode, and manner of death, or to evaluate any disease or injury that may be present for research or educational purposes. This can be further divided into a “forensic autopsy” or a “clinical autopsy”.

A forensic autopsy is one in which a medical examiner determines the time of death, the exact cause of death, and what, if anything, preceded the death. It often includes obtaining biological specimens from the deceased for toxicological testing, and analyzes environmental and chronological factors present upon initial discovery of the deceased. Once everything is gathered together, the examiner’s job is to (as accurately as possible), detail the evidence on the mechanism of the death, and assign a manner of death.

A clinical autopsy is performed to gain more insight into pathological processes and determine what factors contributed to a patient’s death. For example, material for infectious disease testing can be collected during an autopsy. Autopsies can yield insight into how patient deaths can be prevented in the future.

IN THE BEGINNING…

The earliest records of a post-mortem examination were completed by the Greek physician Galen. He studied the symptoms of a patient and then after death, dissected the affected that part of the body. He believed that disease was caused by an imbalance of four fluids, or “humours”. This theory persisted through the Middle Ages, when any challenges to it were thwarted by religious leaders, who thought it a crime to dissect a body without their decree. During the Italian Renaissance, Leonardo Da Vinci and Michelangelo started carrying out their own dissections of the human body for anatomical study. After 1400 years of stagnation the science finally began to advance, and was given a huge boost forward when the Italian anatomist and pathologist Giovanni Morgagni refuted the humoral theory of disease. He introduced the anatomo-clinical concept in medicine, which established anatomy as the instrument to identify the seat and etiology of any disease, making pathological anatomy an exact science. Physicians began to look at disease in a different light and this, along with increasing religious approval for the autopsy, opened the door for continued study.

CIVIL WAR ERA

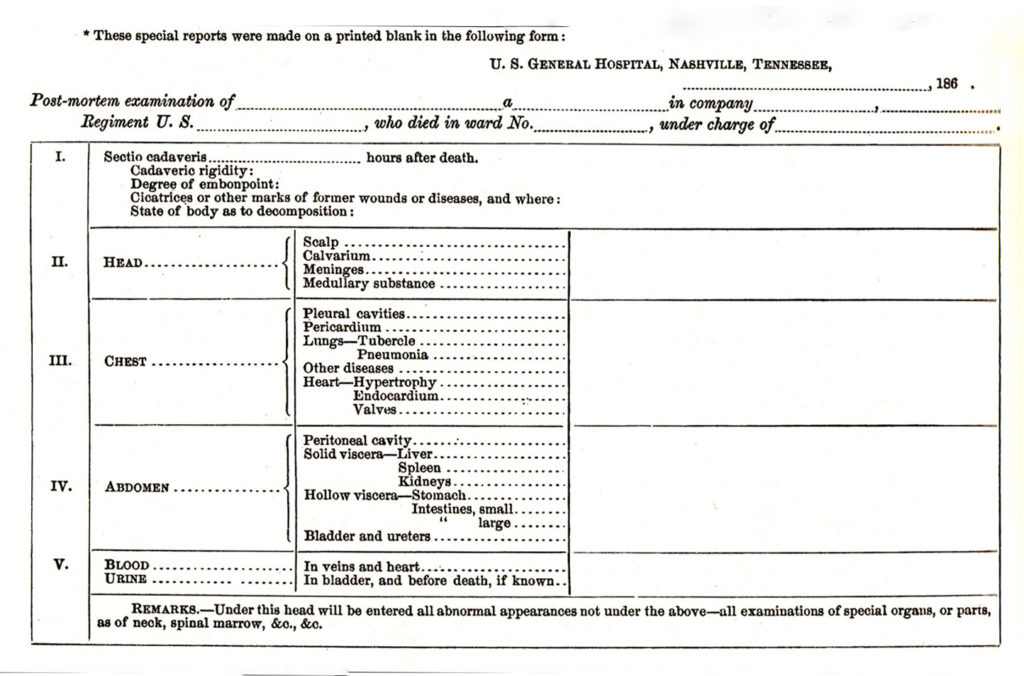

It wasn’t until the 1800’s that the performance of autopsies became increasingly popular. The abundance of corpses during the Civil War allowed physicians to enhance their skills in investigating bodies after death. The Union Army’s Medical Department issued a General Order in May of 1862 in which then-Surgeon General William A. Hammond directed Union medical staff surgeons to collect post-mortem specimens:

CIRCULAR NO.2 Surgeon General’s Office Washington D.C. May 21 1862

Important cases of every kind should be reported in full. Where post mortem examinations have been made, accounts of the pathological results should be carefully prepared. As it is proposed to establish in Washington an Army Medical Museum, medical officers are directed diligently to collect and to forward to the office of the Surgeon General, all specimens of morbid anatomy surgical of medical which may be regarded as valuable together with projectiles and foreign bodies removed and such other matters as may prove of interest in the study of military medicine or surgery. These objects should be accompanied by short explanatory notes. Each specimen in the collection will have appended the name of the medical officer by whom it was prepared.

WILLIAM A HAMMOND, Surgeon-General US Army. ” (From The Army Surgeon’s Manual by Wm. Grace)

The Confederate Army followed suit with a directive issued in August 1864 by Surgeon-General Samuel P. Moore. The directive closes with this statement:

“The medical officers will assist in the performance of such post-mortems as Surgeon (Dr. Isaiah H.) Jones may indicate, in order that this great field for pathological investigation may be explored for the benefit of the medical department of the Confederate Army.”

Surgeon Jones was in charge of the Hospital for Federal Prisoners in Andersonville, Georgia. Andersonville (officially called Camp Sumter) provided Confederate surgeons with a plethora of corpses (who were, for the most part, severely emaciated).

(from medicalantiques.com website)

MODERN ERA

The modern-day autopsy was pioneered by the Austrian physician Karl Rokitansky, who performed over 30,000 autopsies during his career. He was the first to examine every part of the body, with a systematic and thorough approach. His competitor, Rudolf Virchow, was the first to use microscopy to examine each organ carefully. These advances ultimately led to the birth of the medical specialty we know today as Pathology.

POST-MODERN ERA

In more recent times, autopsies have declined while the study of general pathology has flourished. Thanks in part to modern technology, the accuracy of a clinical diagnosis has made the autopsy outdated. Many physicians feel that a post- mortem examination would not reveal any new conditions that were not detected clinically. Today less than 5% of hospital deaths are autopsied as more focus is spent on performing diagnostic tests and providing treatment to patients. However, autopsy findings are still important for furthering research for physicians and remain critical in criminal investigations.

*POST-CIVIL WAR ADDRESSES FOR THE NYC FIRMS

NB: The following information is copied exactly from the entries in the New York City directory.

Hermann turned the business over to his son after May of 1865. During this time, “Hernstein & Son” moved to 2 Liberty and 393 Broadway., where it remained until 1867. The company continued under the name of “Hernstein & Son” until 1867-68, when it was renamed to “Albert L. Hernstein,” and moved to 102 Liberty. In 1869 he moved to 52 Maiden Lane. He remained there until 1871, when he moved to 94 Liberty. In 1872, he changed the name of the firm to “A.L. Hernstein & Co.” In 1873, under the same name, he moved to 146 William. After three years, in 1876, he opened at 54 Chatham; the directory lists “Albert L. Hernstein” and “E. Hernstein” as (makers of) surgical instruments at this address. In 1877, Albert L. is still at 54 Chatham and the “E. Hernstein in business with him is identified as “Esther Hernstein” (Esther was Albert’s wife). One year later, in 1878, E./Esther is not listed with the company which is now called “Hernstein & Co”. In 1879, “Hernstein & Co.” remains at 54 Chatham, but there is also “Albert L. Hernstein” at 54 Chatham and 339 4th Avenue. In 1880, “Albert L. Hernstein” is at 337 4th Ave. (no typo). 1881 is an interesting year – Albert L. is now at 507 1st and 337 4th Avenues, and “Herman Hernstein” is at 503 1st. – both listed under “surg. insts.” In 1882, Albert L. is at the same address, but Herman is not listed as part of the business. Herman died in 1883, and is buried in Beth Olum Cemetery, Queens County, New York.