This is an example of an original Civil War hospital steward insignia, a half-chevron of emerald-green wool with an embroidered caduceus and yellow borders. Regulations for Union hospital stewards called for a half-chevron of the following description: of emerald green cloth, one and three-fourths inches wide, running obliquely downward from the outer to the inner seam of the sleeve, and at an angle of about thirty degrees with a horizontal, parallel to, and one-eighth of an inch distant from, both the upper and lower edge, an embroidery of yellow silk one-eighth of an inch wide, and in the center “caduceus” two inches long, embroidered also with yellow silk, the head toward the outer seam of the sleeve.

During the Civil War, Hospital Stewards of volunteer regiments, however, were known to wear a variety of different uniforms and insignia. Confederate Hospital Stewards’ uniforms and insignia were not officially regulated, but one surgeon recalled that on the uniform many wore, the chevrons on the coat sleeves and the stripe down the trousers were very similar to those worn by an orderly or first sergeant, but were black in color.

Hospital Stewards were among the highest pay enlisted men at $30 a month and were considered to have a very responsible position. They assisted the regiment surgeon, acted as dressers and dispensed medication. Many of them had some medical background. At a time when there were no medical licenses or even a formal requirement of what credentials were necessary to be called a physician, a few hospital stewards were promoted to the position of assistant surgeon. Army regulations specified that men selected as hospital stewards had to be of good character: “temperate, honest, and in every way reliable, as well as sufficiently intelligent, and skilled in pharmacy”. Temperance was an important quality since one responsibility of the hospital steward was controlling and dispensing medicinal whiskey. As he was responsible for keeping many medical records, the steward also needed to be literate and intelligent.

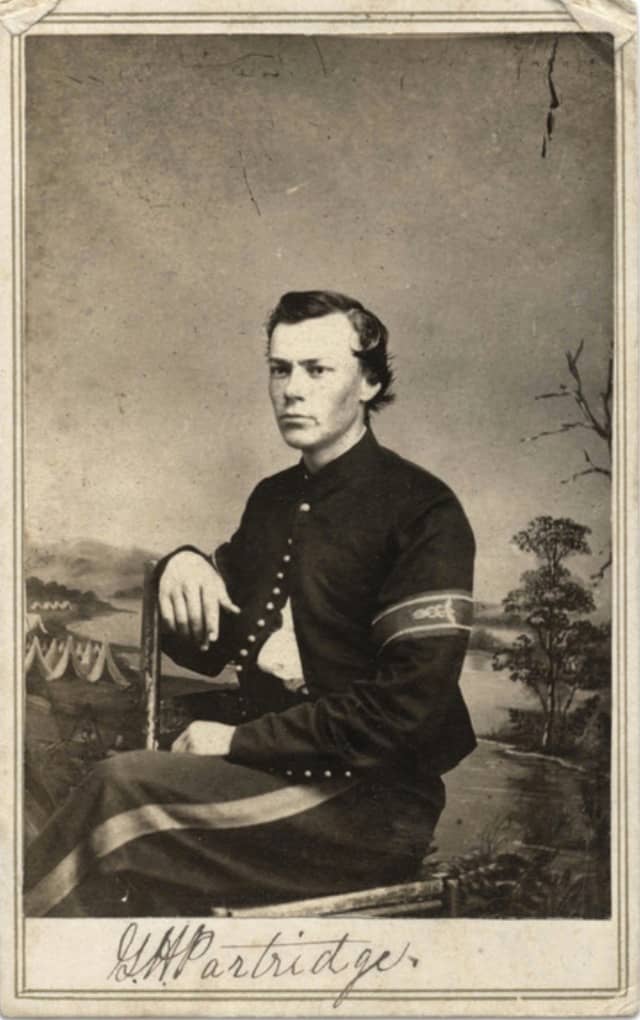

The half-chevron was worn on the sleeve of the jacket, as is shown in the examples below:

George. H. Partridge Hospital Steward 47th Kentucky Infantry

Close-up of insignia

William W. Wallace Hospital Steward

Close-up of insignia

THE HISTORY OF HOSPITAL STEWARDS UP TO THE CIVIL WAR

Hospital Stewards first appeared in the Revolutionary War. On July 27, 1775, Congress authorized the establishment of a Medical Service. In April, 1777, a “Hospital Steward” was allowed for every hundred sick or wounded. Their responsibilities were to receive, dispense and maintain accountability of articles of diet from the hospital commissary. They had no official rank, but were simply soldiers detailed to help an army surgeon or assigned to a hospital. There was no medical training or requirements except to learn on the job.

By September, 1780, Hospital Stewards were given the added responsibility to purchase whatever was necessary for use in the care of the sick and wounded. Their role in the hospital was rapidly expanding and they were expected to handle major administrative and logistical functions in the hospital. They had to be able to read and write and have some background in mathematics, chemistry or pharmacy. Few soldiers of this era had these abilities. In March, 1799, a Hospital Steward was authorized for each military hospital.

In 1813, the reorganization of the Army began and had a major impact on the Army. The pay and allowances for a steward was twenty dollars, the ward master received sixteen dollars, and both received two daily rations. Congress did not extend the authorization for stewards. In order to meet the needs of providing qualified individuals to fill the duties of a Hospital Steward, the Secretary of War authorized the enlistment of individuals for a limited period but without authorization from Congress. Hospital Stewards were taken from the line and the preference was an NCO. Stewards were required to attend three drills a week with the rest of the soldiers. This severely impacted on the care of patients and the regulations were changed to make the steward attend only the weekly inspection and payroll muster. Hospital Stewards were learning patient care by “on the job training” and were often left behind to care for the sick when the surgeon accompanied the troops to the field.

There was not any special pay for the position, and it was not until 1838 that Congress authorized the enlistment of men as stewards. These men were usually privates but drew an additional 15 cents extra per day because of their special duties. These were the first men enlisted for the U.S. Medical Department in the 1800’s. Some of the men were druggists or had some medical training, but most had no special skills in the medical arts. Many of them were appointed from the ranks, but showed some promise to someone to be appointed. Many came from the bands affiliated with the units as they were used as stretcher bearers during battles.

During the Mexican War, the Hospital Steward accompanied the surgeon into battle, dressing wounds and dispensing medicine. The army staff recognized the importance of the Hospital Steward but still no action was taken by Congress to authorize the enlistment of men for the sole purpose of serving in this capacity. In 1847, the Surgeon General had asked Congress several times to authorize positions for Hospital Stewards and he would set up a formal school to train them, however, his requests were turned down.

Finally in 1856, Congress authorized the Secretary of War to appoint as many Hospital Stewards as needed in the army and mustered onto the hospital rolls as “NCO’s”. This action permanently attached the stewards to the Medical Department. It also required that the war department appoint any army Hospital Stewards and assign them to posts, not specific units. This denied the appointment of stewards by regimental commanders.

THE HOSPITAL STEWARD IN THE CIVIL WAR

In April, 1862, a bill was passed by Congress to meet the pressing needs of the Medical Department. This gave the regular army an addition of ten surgeons, ten assistants, twenty medical cadets and as many hospital stewards as the surgeon-general might deem necessary; and it provided for a temporary increase in the rank of those officers who were holding positions of great responsibility. It gave the surgeon-general the rank, pay and emoluments of a brigadier-general; it provided for an assistant surgeon-general and a medical inspector-general of hospitals, each with the rank, etc., of a colonel of cavalry, and for eight medical inspectors with the rank of lieutenant-colonel. These original vacancies were filled by the President by selection from the army medical officers and the brigade surgeons of the volunteer forces, having regard to qualifications only instead of to seniority or previous rank.

The Hospital Steward was selected and appointed to his position and title. In contrast, the male nurse was usually temporarily detailed without change in rank or title from inexperienced enlisted men. The Steward had to apply for his position using an application process.

Dr. Joseph Janvier Woodward wrote “The Hospital Steward’s Manual: For the Instruction of Hospital Stewards, Ward Masters, and Attendants in their Several Duties “, which was published in 1862. Woodward’s (1862) qualifications included:

“18-35 years old, able-bodied, free of disease, honest and upright,” of “good intelligence, having a knowledge of English, able to spell and write correctly,” and “industrious, patient, and good tempered.”

He had to be of good character and must be “temperate, honest, and in every way reliable” (temperance was important as the hospital steward controlled and dispensed medicinal whiskey!) There was a competitive exam to take. He was screened for previous experience and having worked as a druggist or chemist or apothecary clerk in civilian life was a huge plus. Previous experience even as a medical student was greatly beneficial. After the exam, interviews, and references, the appointment had to be confirmed by the Secretary of War. Once the process was successfully completed the Hospital Steward received the rank of NCO (Non-Commissioned Officer). He was “equal to Ordnance Sergeant” and “next above First Sergeant.” The appointment was permanent for the duration of the war and he could not be returned to regular duty. He was the only able bodied man who could not be returned to active duty.

In the manual, Woodward states the medical qualifications of this applicant: “must have…sufficient knowledge of…pharmacy to take charge of the dispensary, acquainted with minor surgery, …application of bandages and dressings, extraction of teeth, application of cups and leeches, …knowledge of cooking.” One should note that the qualifications are much broader than pharmacy. The manual not only included the roles and responsibilities of the Hospital Steward, but also continued to include hospital attendants and nurses.

The roles and responsibilities of the Hospital Steward were numerous and varied depending on his duty location. In the hospital and acting as the pharmacist, he compounded (measured and mixed) prescriptions written in the prescription book by the surgeons, rather than just filling them from a bulk supply. He also verified that the medication was actually administered although he was usually not the person who gave it. As Hospital Administrator, he was responsible for inventory and ordering of medical supplies, hospital supplies, record keeping, and overall hospital administration. His inventory of records was never ending. It included the Steward’s Weekly Report, an enormous spread sheet manually recorded. On it were recorded weekly the number of beds, linen, clothes, dishes, and even spittoons. In the field and on the march his dispensary had to be mobile and he learned to quickly assemble and disassemble it. The Hospital Steward truly was a “workhorse”.

In addition to the roles and responsibilities previously mentioned, Woodward listed one other responsibility. The Hospital Steward was to be the nursing supervisor for the male detailed nurses (enlisted men), but not for the female nurses. Woodward (1862) stated: “enlisted men are under the orders of the surgeon…look up to as their commanding officer…are also under the orders of the hospital steward, to all whose lawful commands they must yield prompt obedience.” The supervisory role was echoed in the South where the Regulations for the Army of the Confederate States, Medical Department (1862) stated “the cooks and nurses are under the orders of the stewards.” In contrast, regarding the female nurses, Woodward stated “she should heartily co-operate with the steward, and strictly obey the orders of the medical officers.” While all female nurses were under the orders of the Surgeon and for some also the supervision of Dorothea Dix, they were not under the orders of the Hospital Steward.

THE HOSPITAL STEWARD AFTER THE CIVIL WAR

General Order 29, published in April of 1887, assigned enlisted members to the new Hospital Corps and permanently attached them to the Medical Department. After one year of service with Hospital Corps, privates were eligible for appointment as acting Hospital Stewards. After one year of probation and passing of another examination, they could be appointed “Permanent” Hospital Stewards. In its first year some 600 privates transferred to the new corps, with only 24 passing their examinations and promoted to acting Hospital Stewards.

On March 2, 1903, the Hospital Corps was disestablished. The terms Hospital Steward and privates of hospital corps were replaced by the terms sergeant and private, with an exception for the master hospital sergeant which was used until 1920.

THE POST-CIVIL WAR INSIGNIA OF THE HOSPITAL STEWARD

During the post-war years, both British and French uniform designs influenced the military uniforms of the U.S. At this time the French had more influence, so the new chevron designed for the Hospital Steward was similar to the French army’s upper arm oblique chevron for quartermasters. The design had a two-inch yellow caduceus on a half chevron of emerald green cloth with ½ inch green edges, separated from the rest of the chevron by a ½ inch yellow stripe. Green was used since the surgeon wore a green sash to indicate his status and his position in the army. This general design continued until 1887.

In 1887 Hospital Corps was established, and a new chevron design denoting the ranks of the Hospital Stewards was introduced, similar to the chevrons worn by all NCO’s in the Army. Hospital Stewards wore full sized chevrons that had three stripes below and one on top with a Red Cross in the center. Acting Hospital Stewards wore the same chevrons except for the stripe on top.