“… A FAT LITTLE FAIRY IN THE SHAPE OF THE PROFESSOR OF ANATOMY”

Elizabeth Blackwell, November 9, 1847 (written on her second day of medical school)

“… LITTLE DR. WEBSTER WAS IN HIS GLORY; HE IS A WARM SUPPORTER OF ELIZABETH“

Henry Browne Blackwell, January 23, 1849 (written on the day of her graduation)

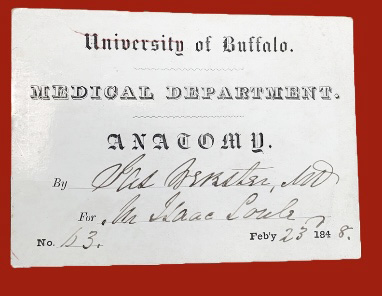

The card shown, dated February 23, 1848, is a ticket to attend the spring session of Dr. James Webster’s lectures in Anatomy at the University of Buffalo. Three months earlier, he had given the same lectures during the winter session at Geneva Medical College, where for the first time in history, one of the attendees was female.

After 29 medical schools rejected her application, Elizabeth Blackwell was admitted to Geneva in October 1847. Her second day there, she attended lectures from a “… fat little fairy in the shape of the Professor of Anatomy… Dr. Webster, the Professor of Anatomy, a little plump man, blunt in manner and very voluble.” Upon her graduation (at the head of her class!) on January 23, 1849 – exactly 11 months after the date on this ticket – Elizabeth Blackwell became the first woman in the United States to earn a Doctor of Medicine degree.

—Elizabeth Blackwell

HER RELATIONSHIP WITH DR. WEBSTER

There are several online references to Dr. Webster and relationship with Elizabeth, some of which portray him in an unfavorable light. Among these is the notion that he “banned” her from the dissection room on the day that the female reproductive organs were demonstrated. To truly understand her relationship with Dr. Webster, we need not any look further than Elizabeth’s own words.

In 1895 she published a book, “Pioneer Work in Opening the Medical Profession to Women.” To recall the details of her experiences at Geneva Medical College she referenced her journals and letters, which recorded her thoughts from the day she entered college, to the day of her graduation.

Her journal entry on her first day of medical school November 8, 1857, notes that she attended five lectures which Dr. Webster did not attend. Inquiring about his absence, she states that “he has been spoken of as a queer man.” 1. On the following day, November 9, her entry reads:

“My first happy day; I feel really encouraged. The little fat Professor of Anatomy is a capital fellow… he will afford me every advantage, and says I shall graduate with éclat.”

In a letter written that same day and sent to her sister, she elaborated a bit more:

“I was introduced to Dr. Webster, the Professor of Anatomy, a little plump man, blunt in manner and very voluble. He shook me warmly by the hand, said my plan was capital… He asked me what branches I had studied. I told him all but surgery. ‘Well,’ said Dr. Lee, ‘do you mean to practise surgery?’ ‘Why, of course she does,’ broke in Dr. Webster. ‘Think of the cases of femoral hernia; only think what a well-educated woman would do in a city like New York. Why, my dear sir, she’d have her hands full in no time; her success would be immense. Yes, yes, you’ll go through the course, and get your diploma with great éclat too; we’ll give you the opportunities. You’ll make a stir, I can tell you.‘ “

This recollection was contemporaneous to the day it occurred, and clearly disputes the notion that Webster was antagonistic in any way to her presence at the college. In fact, he supported (and even championed) her future as a physician.

DR. WEBSTER VOWED TO PROTECT HER FROM MALICIOUS GOSSIP

Webster was keenly aware of the stir she was making in class and in public, where the townswomen had concluded that she was either a “bad woman” or “insane”, and resolved to shield her from further distraction:

“Dr. Webster came to me laughing after the first lecture, saying: ‘You attract too much attention, Miss Blackwell; there was a very large number of strangers present this afternoon – I shall guard against this in future.“

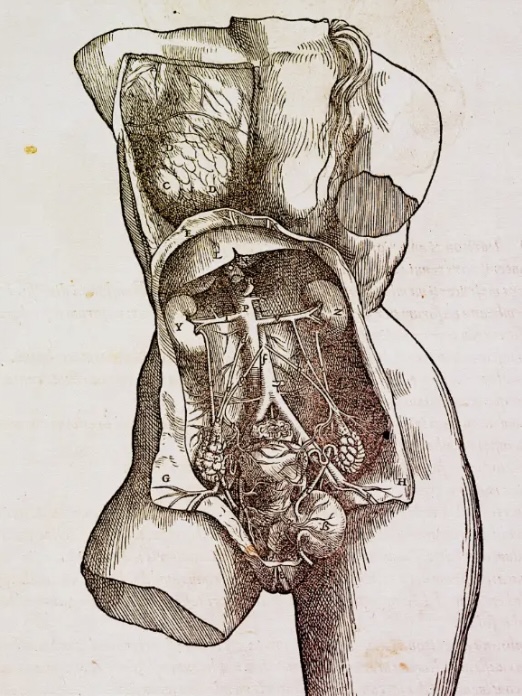

ON HER SUPPOSED “BAN” FROM THE DISSECTION ROOM

(FROM HER JOURNAL)

Some sources assert that Webster “banned” her from the dissection room on the day the the female reproductive organs were demonstrated. In fact, his “request” was not a “ban”, and she did not believe that he was to blame:

November 15. – To-day, a second operation at which I was not allowed to be present. This annoys me. I was quite saddened and discouraged by Dr. Webster requesting me to be absent from some of his demonstrations. I don’t believe it is his wish. I wrote to him hoping to change things...Dr. Webster seemed much pleased with my note, and quite cheered me by his wish to read it to the class to-morrow, saying if they were all actuated by such sentiments the medical class at Geneva would be a very noble one.”

JAMES WEBSTER, M.D.

(1803 – 1851)

James Russell Webster was born in England on December 26, 1803. At an early age he emigrated to this country with his parents, and settled in Philadelphia, where his father became an eminent bookseller and publisher, and established the Medical Recorder (his son would eventually be one of the editors). Initially destined to become a lawyer, his interest turned to the study of medicine, in which anatomy soon became his favorite pursuit. He pursued his studies in Baltimore and Philadelphia, and after attending three full courses of lectures, two of which were in the University of Pennsylvania, he graduated at the latter in March, 1824, at the age of 20 years.

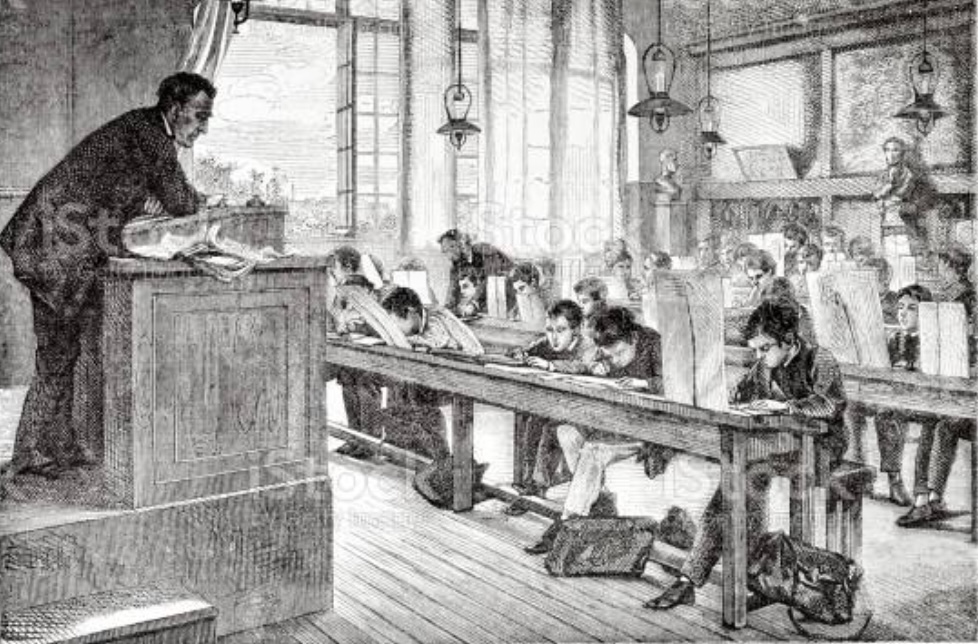

As a teacher of anatomy, his lectures were clear, precise, and accurate. He was exceedingly fluent and animated as a teacher, never failing to command the whole attention of his class, and enjoyed a high degree of popularity with his students. His private classes in Philadelphia were crowded, and he succeeded in imparting to his students the same enthusiasm which he himself felt in the study of his favorite science.

In 1834 he moved to New York City, where in addition to his general practice, he developed a reputation as a surgeon especially skilled in the treatment of diseases of the eye and ear. In 1842 he was appointed Professor of Anatomy in Geneva Medical College, and took up his residence in the city of Rochester – where, in a short time, he became one of the most prominent surgeons in western New York.

In 1845, when the medical department of the University of Buffalo was organized, Dr. Webster was appointed Professor of Anatomy. Four years later, he was elected to the Chair of Anatomy in 1849. He continued to lecture until 1851, when he resigned from ill health. He died of heart disease in Louisville, Kentucky in 1854, at the age of 51.