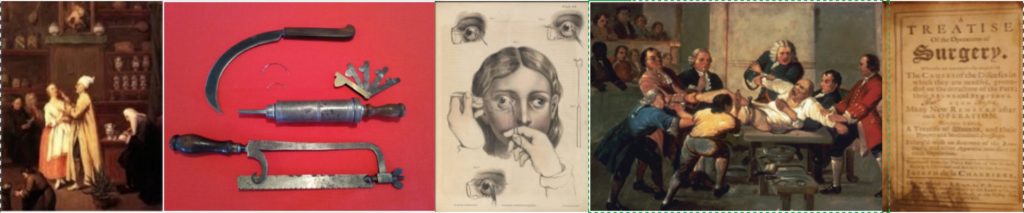

The 18th century to pre-Civil War period was an interesting time in the history of medicine. In this same period of time, the Industrial Revolution occurred. It was marked by many inventions and innovations that transformed an agrarian-based economy to one based on large-scale production.

Curiously, this huge wave of new inventions and technological advancements, many of which were scientific in nature, did not expand very far into the realm of medicine and surgery. The invention of the power loom (“Spinning Jenny”), locomotive, steam engine, telegraph, dynamite and photograph caused a sea change in societal organization and economies. On the other hand, innovations in the medical world occurred more in fits and spurts. True, there were salient moments of achievement, ones that would resonate far into the future. But the physicians and surgeons of the 18th and early 19th centuries were still handicapped by wrong ideas about the body, and practiced medicine accordingly. For each idea that was a leap forward towards the realm of modern medicine, there were a multitude of old ideas that hobbled progress.

Rene Laeannec invented the stethoscope in 1816, which revolutionized heart and lung exams, and remains a crucial diagnostic instrument to physicians over 200 years later. At that same time, the belief that diseases (such as pneumonia) and conditions (such as heart failure) were due to an imbalance of the four bodily humors persisted, which fueled the ubiquitous use of emetics, laxatives and purgatives, and the ever-popular bloodletting.

In 1847, Dr. Ignaz Semmelweiss made the startling discovery that the incidence of puerperal fever (“childbed fever”) was drastically reduced if he washed his hands in a chlorinated lime solution before examining the mothers. Despite evidence that showed the mortality rate to be less than 1% when handwashing was performed, it was in direct conflict with the prevailing notions about disease. And, because he could not prove why it worked, he was roundly mocked by other physicians and surgeons, some of whom were downright offended by his suggestion. It would be another 20 years before Joseph Lister, acting on Pasteur’s findings, proved the antiseptic powers of carbolic acid and forever changed the practice of surgery. Meanwhile, Semmelweiss died from gangrene in wounds inflicted by guards in the asylum to which he’d been committed, because he would not cease proselytizing about his discovery. (In one of the most odd – and sad -coincidences in medical history, Semmelweiss died the day after Lister’s successful demonstration of antiseptic practice in surgery, but was likely too ill to appreciate his vindication.) Nevertheless, when Lister came to America in 1876 to share his discovery, the noted physician Samuel Gross is quoted as saying: “Little if any faith is placed by any enlightened or experienced surgeon on this side of the Atlantic in the so-called carbolic acid treatment of Professor Lister”. “Enlightened”, my foot. Teaching some old dogs new tricks, particularly those across the pond, was going to be harder than he thought.

Although ancient Sumerians and Egyptians recognized the power of willow bark to treat pain, acetylsalicylic acid (aspirin) was not created until 1853 by Charles F. Gerhardt. Unfortunately, Gerhardt did not use or market his modified version of salicylic acid (or the bottles today would read “Gerhardt” instead of the still-Teutonic-but rolls-off-the-tongue-easier “Bayer”). Meanwhile the widespread use of mercury and other poisonous compounds to treat various diseases and medical conditions continued unabated for several decades into the future. Even Abraham Lincoln relied on his “blue mass pills” (basically elemental mercury mixed with milk sugar, marshmallow, rose oil and a hint of licorice) either to treat his “melancholia” or regulate his bowel habits – or perhaps both.

Although it would not be safe and reliable until 1901 when Karl Landsteiner identified blood groups, transfusion from one human to another to treat hemorrhaging was first performed in 1818. Yet widespread bloodletting continued to be performed purposefully to treat various diseases and ailments and – hard to believe – restore health. (It is worth mentioning that as it turned out, bloodletting did treat hypertension, hem0chromatosis and porphyria cutanea tarda – so patients with those ailments did benefit from the practice (and the physicians who lucked out with such patients no doubt looked like heroes.)

Early inhabitants of South America knew that the bark of the quinquina tree would treat fevers, but it was not until 1820 that the active ingredient in the bark was isolated – and called quinine. This would be used to treat malaria until the 1970’s. Yet physicians were not swayed from their belief that miasma (“bad air”), the result of insects’ waste polluting the air, water, soil and fog, was the cause of major infectious diseases, wound infections and epidemics like the Black Death. The first major discovery of a disease vector did not occur until 1897 (and coincidentally, had to do with finding the malaria pathogen inside a dissected mosquito.)

Edward Jenner pioneered the concept of vaccination by creating the smallpox vaccine, the world’s first vaccine, and proved its efficacy in 1758. This paved the way for mass vaccination and practical elimination of smallpox in Europe by 1900 (and on a global scale by the 1970’s). Yet the “germ theory of disease” was completely foreign to physicians of the day, until Louis Pasteur’s experiments in the mid-1800’s paved the way for Koch’s Postulates nearly three decades later. Koch’s Postulates still hold true today, albeit with some tweaking and refinements given the discovery of viruses and intracellular bacterial pathogens.

It was a time marked by a clash between two worlds. Old, entrenched beliefs that had been blindly accepted for decades were beginning to be challenged by more critical ways of thinking, and paved the way for modern medicine many years later.