And the Coins Driven into a Soldier’s Groin by a Bullet!

“THIS POCKET BOOK … BEARS THE BLOOD STAINS FROM MY HANDS AFTER OPERATING (AMPUTATING ) THE ARM OF ONE OF THE 5 NY ZOUAVES (DURYEAS) THE SURGEON IN COMMAND RUFUS GILBERT NOT BEING ABOUT TO DO THE OPERATION”

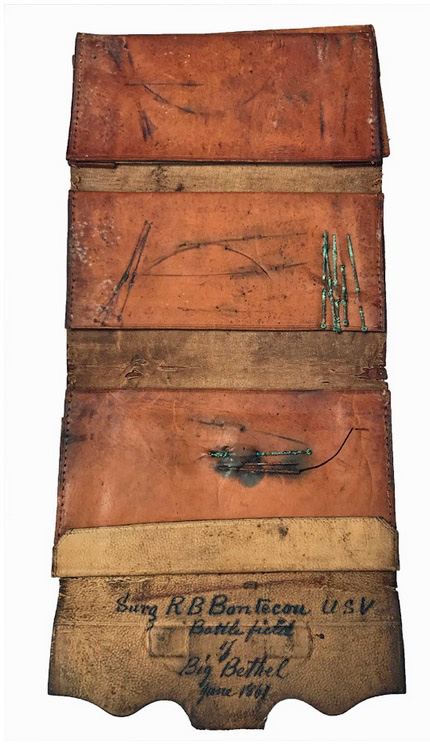

THE BLOODSTAINED WALLET

“Surg. R.B. Bontecou USV

Battle field

of

Big Bethel

June 1861″

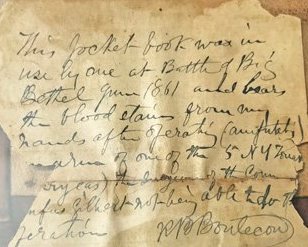

“This pocket book was in use by me at Battle of Big Bethel June 1861

and bears the blood stains from my hands after operating (amputating)

[the] arm of one of the 5 NY Zouaves (Duryeas)

the Surgeon of the command Rufus Gilbert not being able to do the operation

R B Bontecou”

“These coins were driven into [a] soldier’s groin by a bullet

in the War of the Rebellion”

This item is truly a museum piece. It is unusual on many levels, not the least of which is, it rewrites history.

This is the folding leather pocket surgical wallet of Reed Bontecue, M.D., who wrote a note kept inside the wallet, and signed it – that it was bloodstained from his hands, following an amputation on a 5th NY / Duryee Zouave at the Battle of Big Bethel. The details in his note allow us to postulate that this may have been the first recorded battlefield amputation of the Civil War. (nb. The first recorded amputation of the Civil War was performed on April 26, 1861, by Dr. Norman Smith, on a soldier of the 8th Massachusetts Militia during the Baltimore Riot. Details and info are here, along with photos of his surgical set: https://medicalantiques.com/civilwar/Civil_War_Articles/Norman_Smith_amputation_documents.htm).

In addition to the wallet, with the surgical needles fused into place from dried blood, there are other grisly relics: three coins that he removed from the private parts of another injured soldier, when a projectile drove them from his trouser pocket into his groin.

For those finding it unusual that Bontecou would take the time to document these grisly relics, it should be noted that in his younger years, he amassed a large collection of botanical and zoological specimens, and was undoubtedly in the habit of diligently cataloging items that had importance to him. (This same attention to detail would be invaluable in the post-Civil War years when he created an enormous database of medical photographs, documenting the outcome of severely injured soldiers and sailors.)

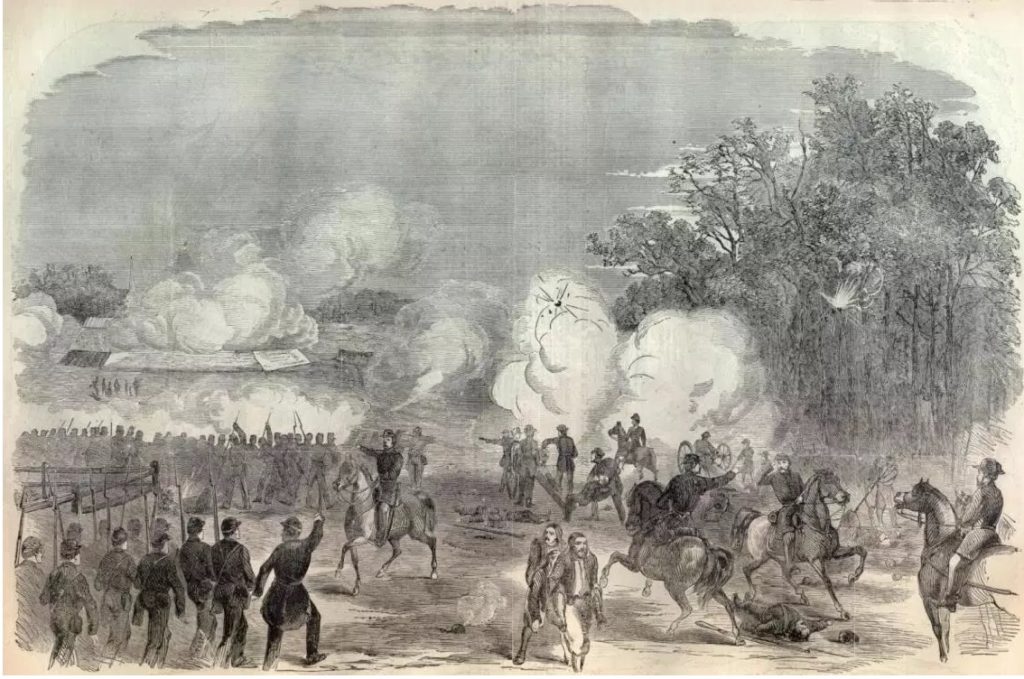

Dr. Reed Bontecou was commissioned Surgeon of the 2nd New York Infantry in May 1861, on the same day that Dr. Rufus Gilbert was commissioned Surgeon of the 5th New York Infantry, also known as “Duryee’s Zouaves”. The battle of Big Bethel took place on June 10, 1861, and although both regiments were involved, Duryee’s Zouaves were chosen to lead the way, with the 2nd New York Infantry in support.

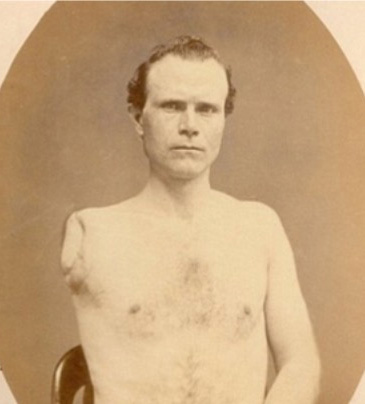

Fortunately, the battle occurred in the early years of the Civil War, and the names of every member of the Zouaves who were wounded or killed in the battle, along with their specific injuries, were reported and published in the New York Times. Of the 13 Zouaves listed as wounded, there was only one soldier, Private John Dunn, of Company H, who had an injury severe enough (his right arm was shattered by a cannon ball) to require amputation.

This is where some confusion – and historical inaccuracy – arises. Newspaper accounts state that Dr. Rufus Gilbert performed the operation, and specifically mention Pvt. John Dunn as his unfortunate patient. Despite the awful injury – Dunn’s right arm was amputated – the story is tinged with patriotic idealism. Reportedly, Dunn stated that he “could not have lost it in a nobler cause.” One recent book claims that Gilbert was later “decorated” for performing the first (recorded) battlefield surgery under fire, but I was not able to substantiate this. Over the decades, many, many books and articles have continued to credit Dr. Gilbert for performing the first amputation of the Civil War.

amputation of his right arm

(not John Dunn)

Dr. Bontecou’s note tells a completely different story, and clearly attests that he was the one who performed the operation when – for whatever reason – Dr. Gilbert was unable to do so. Both physicians had been in practice for at least five years prior to the Civil War, but Bontecou was the senior physician between them, being eight years older than Gilbert, with an additional six years of experience. We can only speculate why Dr. Gilbert was unable to do the operation – perhaps he began the operation, but it was too technically challenging for him to continue. I could find no other mention of Bontecou’s name in connection with the operation, nor is there any indication that Dr. Gilbert made any attempt to correct the facts afterwards. There is no question that both surgeons performed under exceptionally bad conditions, under enemy fire, and did the best they could. Both went on to have illustrious careers post-war, and made their mark in not only in the medical and surgical field, but in other areas as well.

It is possible that Dr. Bontecou was too much a gentleman to correct the facts and change the prevailing story. Maybe his ego was not the sort that demanded he receive credit for what was, in retrospect, a historical moment. Or perhaps, just keeping this highly personal relic among his personal effects as evidence of the “real story” of the first recorded amputation of the Civil War, knowing that the facts would one day come to light, was sufficient.

THE WOUNDED SOLDIER

Big Bethel was one of the earliest land battles of the Civil War, and was the first engagement of the noted Duryee’s Zouaves. These facts, along with the relatively small number of killed and wounded in the regiment, resulted in the New York Times publishing Adjutant Hamblin’s detailed report of the killed (4) and wounded (13). His report of the wounded is almost laughable in view of the carnage that would occur in the years to follow: it notes that two soldiers were “slightly wounded from a splinter.” Fortunately, his report allows us to verify the identity of the soldier whose terrible injury resulted in this grisly relic, the sole proof of Bontecou’s historical achievement. There was only one Zouave who had his arm amputated at Big Bethel, and that was indeed Pvt. John Dunn.

PRIVATE JOHN DUNN, COMPANY H, DURYEE’S ZOUAVES

Service records indicate that John Dunn was 20 years of age when he enlisted in the 5th New York Infantry/Duryee’s Zouaves on April 25, 1861. Nothing is known of his pre-war life, other than he was born in Ireland. He mustered into Company H on May 9, and one month later first “saw the elephant” at Big Bethel, Virginia. On June 9, 1861, the Captain of Company H, Hugh Judson Kilpatrick (later a Brig-General) took fifty privates from his company, along with a handful from Company I, and became the Advance Guard. The following day they were on the front lines, and while engaged with Confederate forces, Dunn lost his right arm to cannon shot and subsequent amputation. Private Dunn was discharged for wounds at Baltimore on August 21, 1861.

Dunn’s life after the war took a tragic turn. Perhaps he suffered what we now know as “post traumatic stress syndrome”, perhaps he had alcohol or opiate addiction issues, perhaps he suffered a psychotic break – we will never know. But by 1870, he was housed at New York City’s Asylum for the Insane on Ward’s Island, where he died prior to 1880. Most probably, his remains lie mingled with thousands of other patients in a common grave on Ward’s Island. Private Dunn paid the ultimate price for his country, and should forever be remembered as the soldier who suffered the first battlefield amputation of the Civil War.

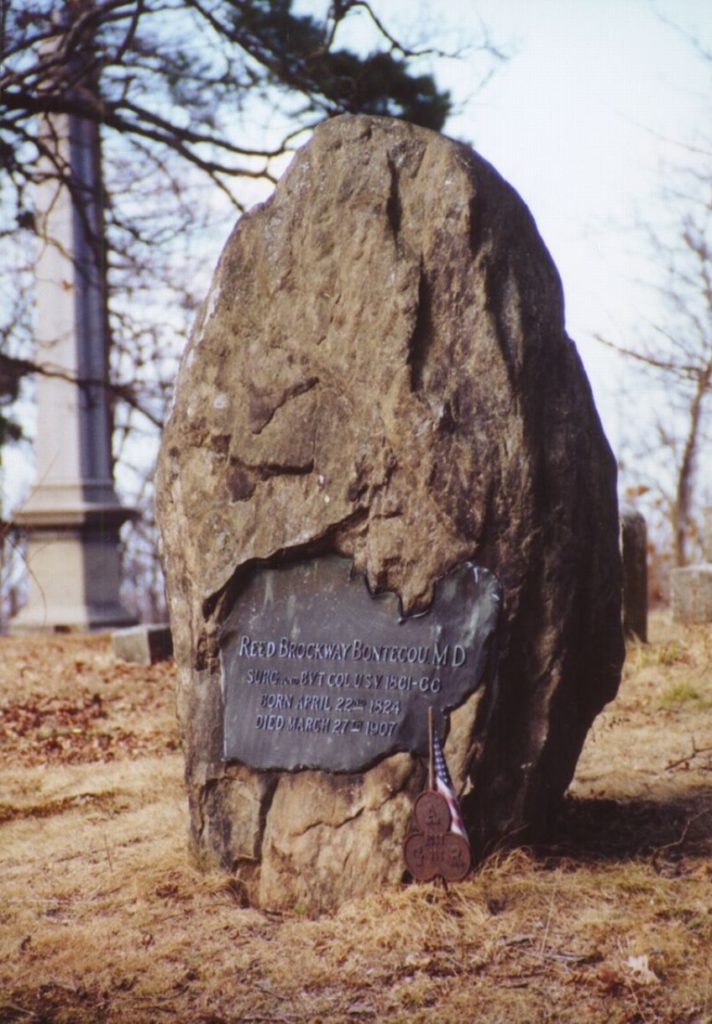

DR. REED BROCKWAY BONTECOU, SURGEON U.S. VOLUNTEERS (1824 – 1907)

Born in Troy, New York, he developed his scientific interests early on. Pursuing an interest in natural history, he spent his early life lecturing in Botany and Zoology and amassed a collection of various types of biological and zoological specimens for scientific study. Returning from a trip to the Amazon, he decided to pursue medical studies, and in 1844-45, attended lectures at the University of the City of New York, earning his Medical Degree from Vermont’s Castleton Medical College in 1847, and began medical practice in Troy, New York. He also became surgeon for the 24th New York Militia.

His aptitude as a surgeon became evident when in 1856, he treated a patient who had sustained a cervical fracture, with complete general paralysis, and the patient recovered enough to resume his career as a house painter. This was the first case of its kind treated successfully, in the country.

In April 1861, he was commissioned a surgeon with the rank of Major in the 2nd New York Volunteer Infantry. That September, he was commissioned into the U.S. Volunteers Medical Staff, and was appointed Medical Director of the U.S. Army Hospital (Hygeia) at Fortress Monroe. From October 1863 to June 1866, he was Surgeon-in Charge of the U.S. Army General Hospital, known as Harewood Hospital, located in Washington D.C., one of the largest hospitals of the war.

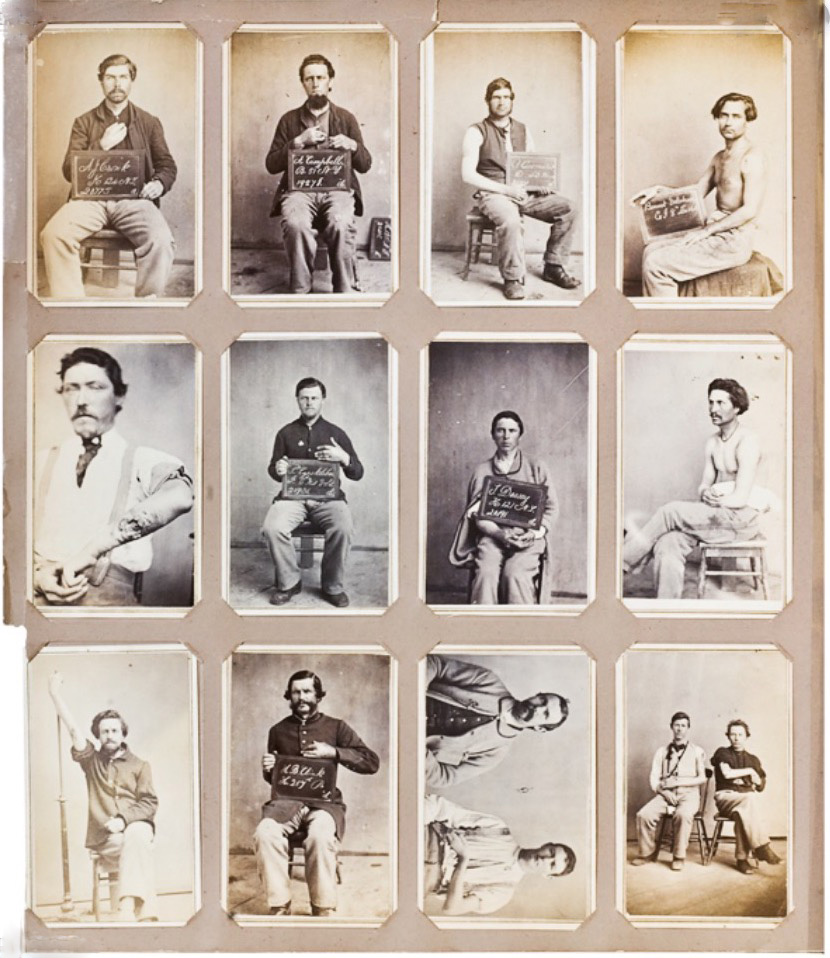

In 1862, Surg-General William Hammond had asked surgeons to submit “morbid specimens” to the new Army Medical Museum, in order to improve patient care. Over the next 2 years, Hammond requested surgeons to submit photos of specimens, and unusual medical cases. While at Harewood, Bontecou turned his interest in photography to the wounded soldiers there, and began using photographs to record pre- and post-operative care of hundreds of soldiers. Bontecou viewed amputation as a last resort, preferring to excise the ends of fractured bones and resect joints whenever possible, to spare the limb. He was proficient at this, having performed the first shoulder-joint resection (in 1861) and first knee-joint resection (in 1863) due to gunshot wounds.

He was brevetted Lieut-Colonel and then Colonel of U.S. Volunteers at the end of the Civil War, and when Harewood Hospital closed in 1866, he returned to private practice. In 1870, he also became acting assistant surgeon at Watervliet Arsenal. He maintained a successful surgical practice for four decades after the war, and was known as a man with a genial temperament, whose career of sixty years spanned an immense field of activity and achievement.

DR. BONTECOU’S POST-WAR CONTRIBUTIONS TO MEDICAL PHOTOGRAPHY

One of his greatest accomplishments is his collection of hundreds of pre- and post-operative soldier photographs. His donation of these, along with thousands of surgical specimens, made him the largest single contributor to the Army Medical Museum.

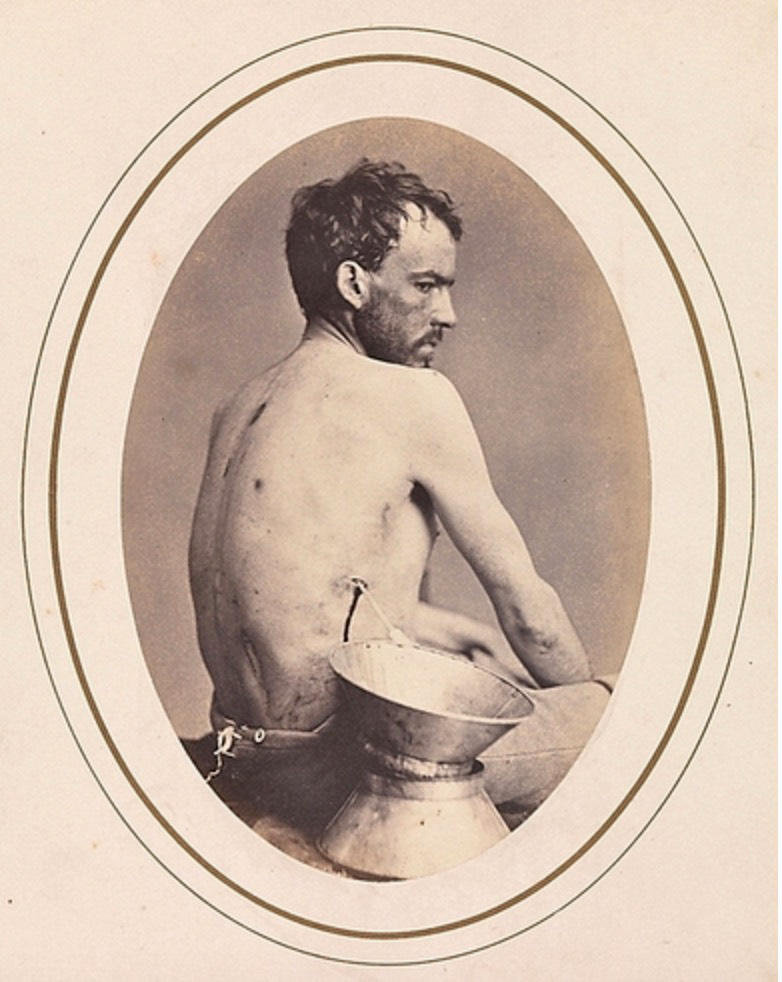

In 1863, when he was named chief of Harewood Hospital in Washington, D.C., Dr. Bontecou began using photography to document wounded soldiers pre- and post-surgery. When Pvt. Lewis James Matson of the 2nd New York Cavalry suffered an injury that required amputation of his left leg at the knee, Dr. Bontecou’s camera chronicled the successful results. Dr. Bontecou’s postwar photography was a stark and chilling contrast to the sentimental CDVs his contemporaries photographed in the hopeful early days of the War. A particularly dramatic photograph featured Corporal Israel Spotts of the 200th Pennsylvania Volunteers. The albumen silver print graphically depicts the young man’s injuries with the bowl into which pus was drained from an infected lung serving as a focal point. Dr. Bontecou’s portraits stripped away the rosy idealism that sparked the conflict and replaced it with the brutal and unflinching reality of its bloody aftermath.

ISRAEL SPOTTS, CORP. 200th PENN. INF.

PHOTOGRAPHS BY DR. BONTECOU

Dr. Bontecou continued photographing wounded soldiers until he left the military in June 1866. He resumed his surgical career, later becoming an assistant surgeon at Troy’s Watervliet Arsenal. He managed to preserve his professional reputation after a personal indiscretion led to a divorce from his wife. Eighty-three-year-old Dr. Reed B. Bontecou died after a brief illness in 1907, and many of the photographic images for which he remains best known can be found at the Army Medical Museum and Library and within the six-volume series, The Medical and Surgical History of the War of the Rebellion (1861-1865).

Were it not for Dr. Bontecou’s passion for collecting and documenting (first) natural specimens, and (later) medical and surgical specimens, the relics shown here would not even exist. I venture to suggest that it was the preservation of these historical artifacts, along with the context in which they occurred, that was most important to the man, rather than the “claim to fame” they would have allowed him to justly make.

HIS GRAVE – MOST UNUSUAL, AND YET A FITTING TRIBUTE TO THE MAN

WHO WAS THE BEDROCK OF MEDICAL PHOTOGRAPHY