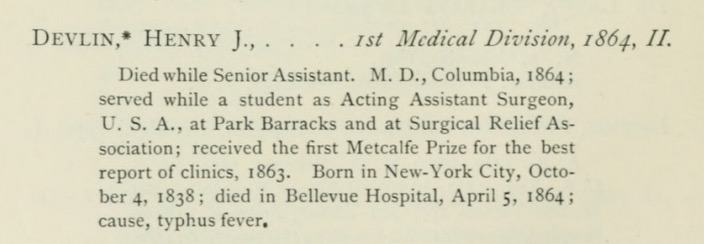

WINNER OF THE FIRST METCALFE PRIZE AT COLUMBIA COLLEGE OF PHYSICIANS AND SURGEONS

HE DIED MONTHS LATER OF TYPHOID FEVER – CONTRACTED WHILE HOUSE PHYSICIAN AT BELLEVUE HOSPITAL DURING THE CIVIL WAR

“Are they more heroic who die in battle?” – Robert J. Carlisle

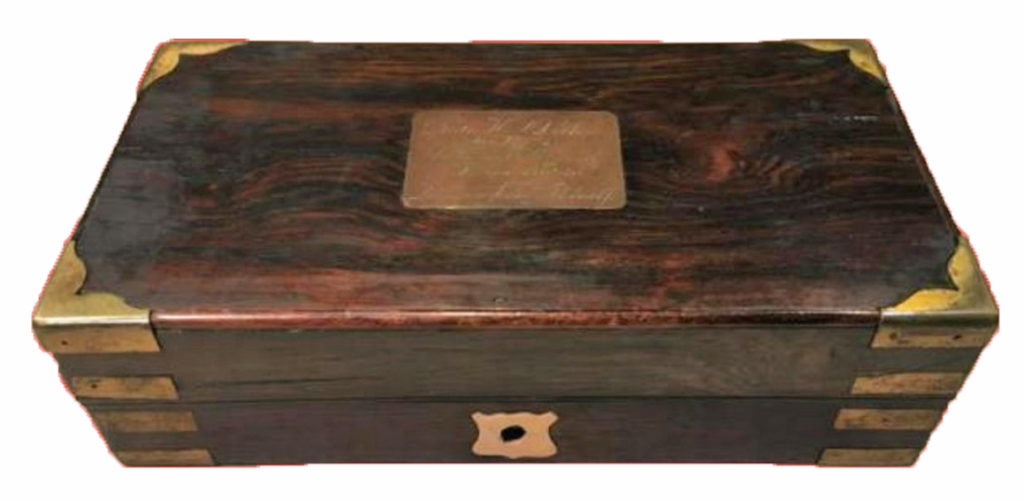

This is a rare find, a one-of-a-kind set, presented as a prize to Dr. Henry J. Devlin for his academic achievement. Only months after receiving this, he succumbed from typhoid fever, contracted while treating patients at Bellevue Hospital.

He was 25 years old.

An engraved plaque on the lid attests to the presentation. Dr. Devlin was the first recipient of Metcalfe (also spelled Metcalf) Prize, awarded for scholarship, a most distinguished honor.

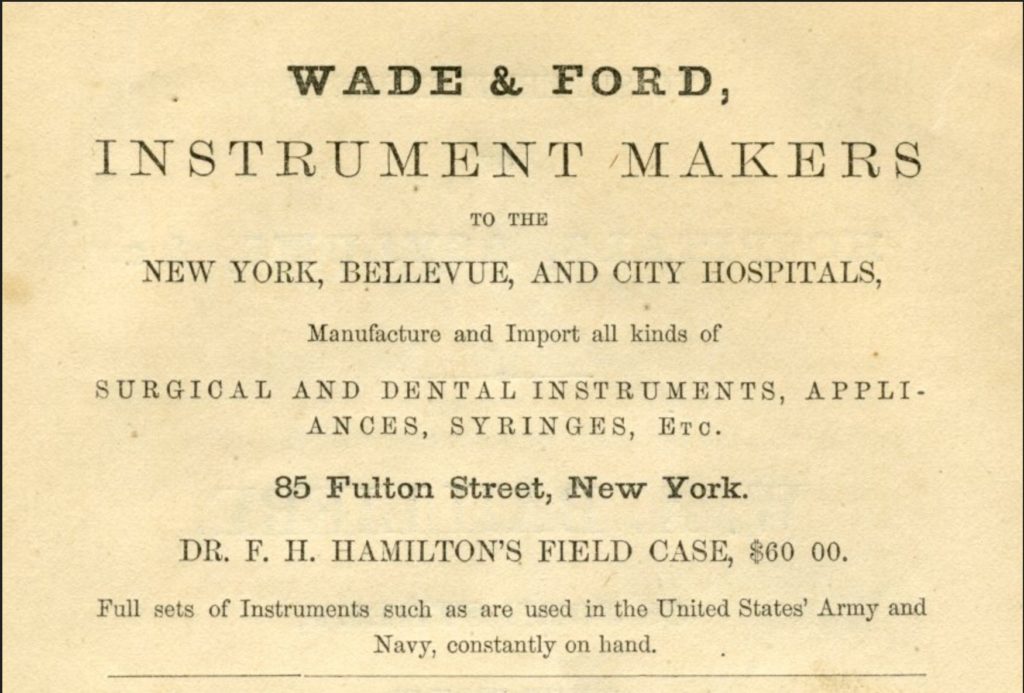

This set contains many of the original instruments. It has the usual complement of post-mortem instruments: bone saw with removable handle, surgical hammer, surgical knife, enterotome, retraction chains, scalpels and tenaculum. The one thing it is missing, judging from the shape of the empty space, is the costotome (rib shears). Seven of the instruments are marked “Wade & Ford NY”, and the large knife is marked “Tiemann & Co.” in the Old English font. Wade & Ford was a known supplier to Bellevue and the city hospitals of New York:

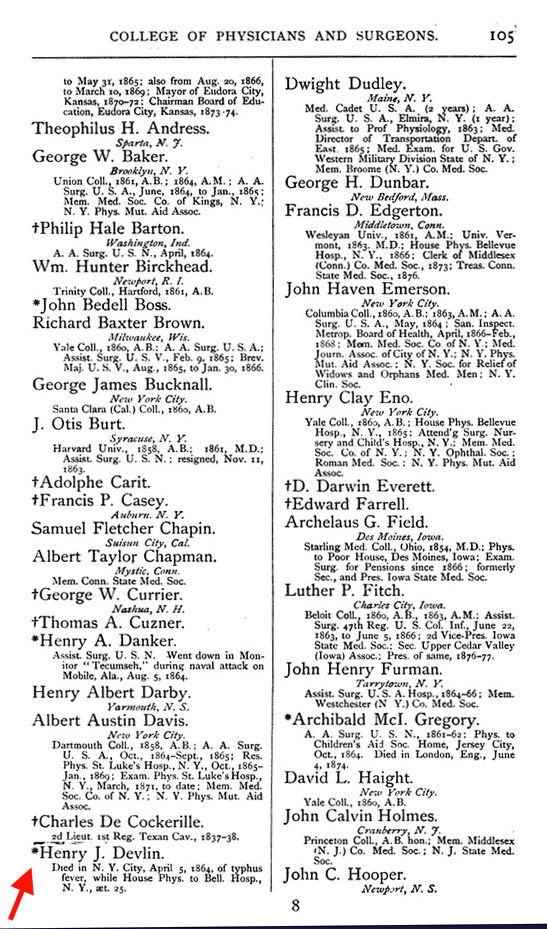

HENRY J. DEVLIN, M.D. (1838 – 1864)

I felt it appropriate to try and find out as much as possible about the life of Dr. Henry J. Devlin. What may have been an illustrious career was cut short, as a result of attending to desperately ill patients under horrendously demanding conditions. Henry died of an illness which today can be prevented by a vaccine – and, even without vaccination – now has a fatality rate of less than 1%, due to antibiotics.

Attempts to find out the details of Dr. Devlin’s life have yielded bits and pieces. His mother, Eliza, was born about 1818 in Ireland. Presumably she was married at one time to a man named Devlin, who was Henry’s father. Her second marriage was to John A. Griffith, born 1818 in London, England. He made his wealth as the owner of a cooperage business. They lived at 42 Hudson Street in Manhattan. When John married Eliza, young Henry became his step-son. In the 1850 Federal census Henry is listed as “Henry Griffin”. In the 1855 New York census, Henry is listed as Henry D. Griffin, age 17, born in New York. Whoever gave the information to the census enumerator gave Henry’s surname of Griffin. Whether he was legally adopted is unknown, but he went by his birth surname as an adult. In the 1850 census, Henry has three brothers (full or half is not known), one sibling named James, two years older, then John A., ten years younger, and Alfred, twelve years younger. James and Henry were probably the issue of Eliza’s first marriage, and John A. and Alfred were from her second marriage.

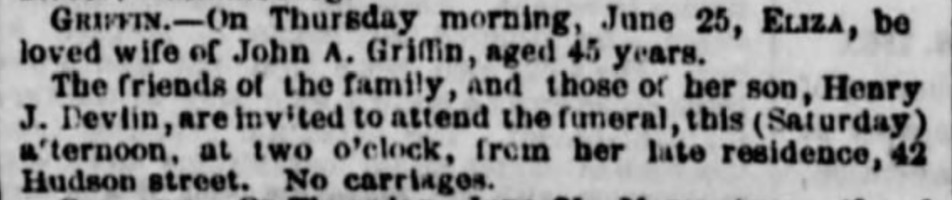

There is little doubt that Henry’s mother’s remarriage to a wealthy man enabled Henry to pursue a career in medicine. Whether Eliza lived long enough to appreciate Henry’s achievement is not certain. Her death was in June, 1863 – 10 months before he died.

With his stepfather as benefactor, Henry attended Columbia College of Physicians and Surgeons and was awarded his M.D. degree in 1864 (n.b. it may have been awarded posthumously.)

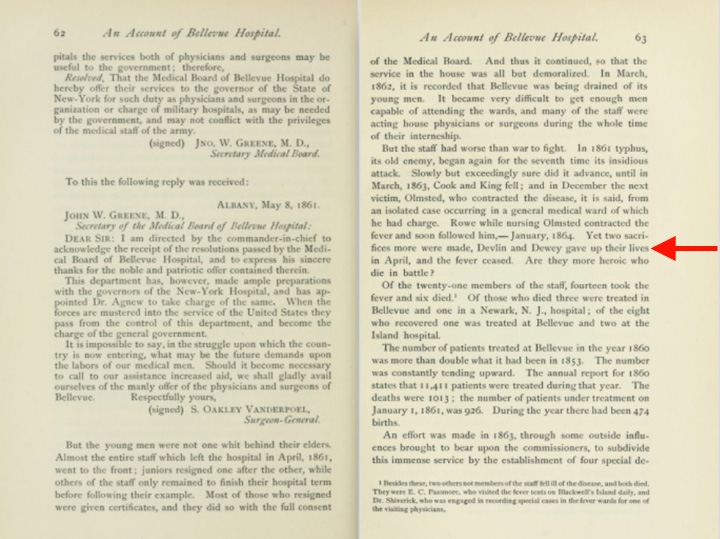

The book “An Account of Bellevue Hospital…” written by Robert J. Carlisle in 1893, gives us the best “biography” about Henry:

“Park Barracks” probably refers to the barracks at Battery Park. By the middle of May 1861, almost a month into the Civil War, most New Yorkers still swelled with enthusiasm for the Union cause, and the new war was already making a physical transformation upon the city. The illustration below is from Harper’s Weekly, and is of the temporary barracks built in front of City Hall in 1861 to accommodate gathering troops from New York and beyond (you can see City Hall towering in the background.) More troop accommodation would soon be built throughout the city. One accountdescribes “great barracks built in Battery Park consisting of an officers’ marquee and a large number of tents.” By 1862, when it became clear that the conflict would not reach a swift resolution, the city removed all temporary tents and barracks from public parks but left the structures in City Hall Park intact.

Carlisle’s account notes that the onset of the Civil War in April 1861 resulted in a large egress of hospital staff, many of whom were sent to the front. Still others resigned in their wake, leaving fewer remaining house staff to shoulder the enormous burden of attending patients, many of whom were ill with typhus and typhoid fever and filled the beds in Bellevue’s wards. Out of the 21 remaining staff members, 14 became ill and 6 died – and one of them was Henry J. Devlin:

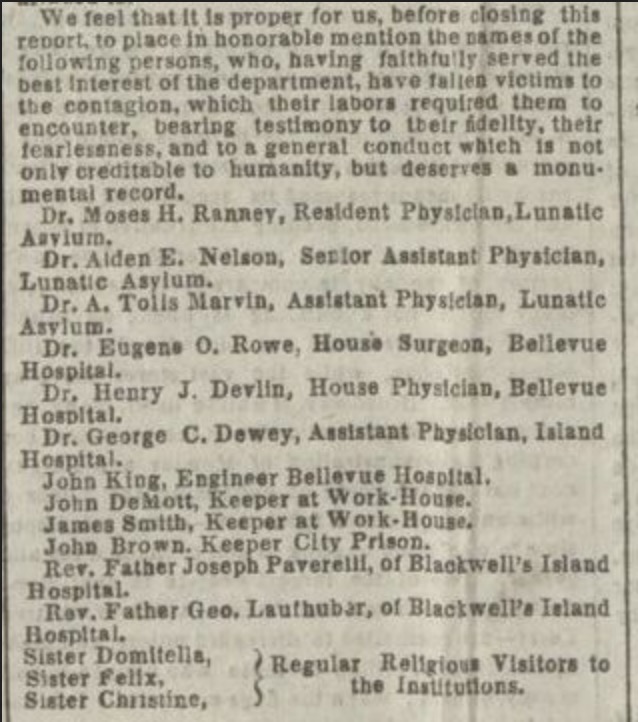

The Officers of the Commission on Public Charities and Correction published the abstract of their fifth annual report, for the year 1864, in the April 22, 1865 edition of the New York Times newspaper. Near the end of the lengthy report is this paragraph:

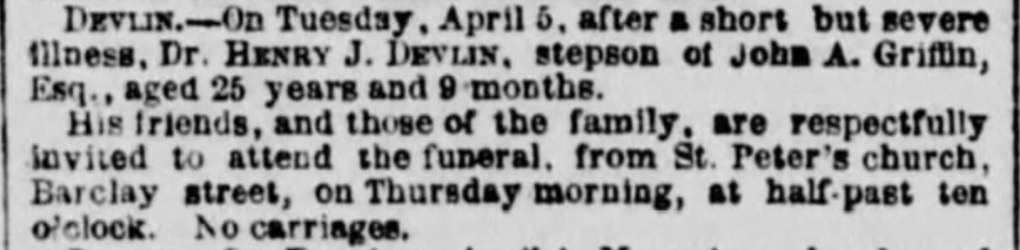

Henry’s death was noted in the New York Daily Herald on Wednesday, April 6, 1864:

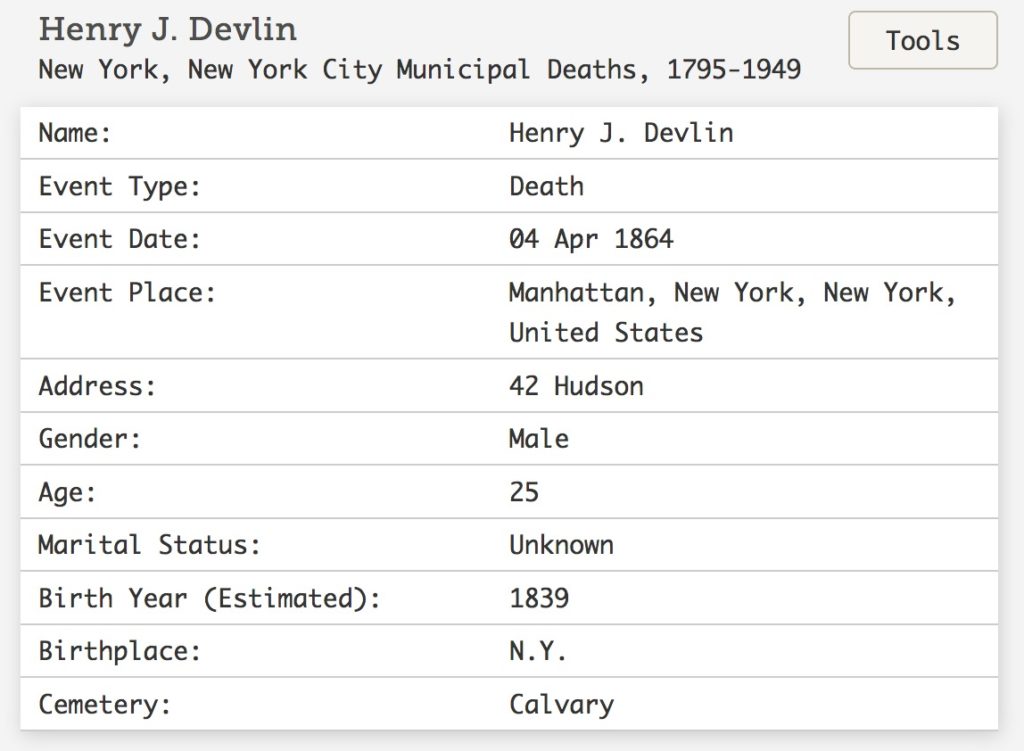

According to the information in the New York City death record shown below (which mistakenly shows his date of death as April 4, instead of April 5), Henry J. Devlin still lived at the family home at 42 Hudson Street (in what is now Tribeca) and was buried in Calvary cemetery in Queens, New York. Established in 1848, Calvary cemetery is a Roman Catholic cemetery with about 3 million burials, the largest number of interments of any cemetery in the United States; it is also one of the oldest cemeteries in the United States. As of this date, there is no photo online of his grave.

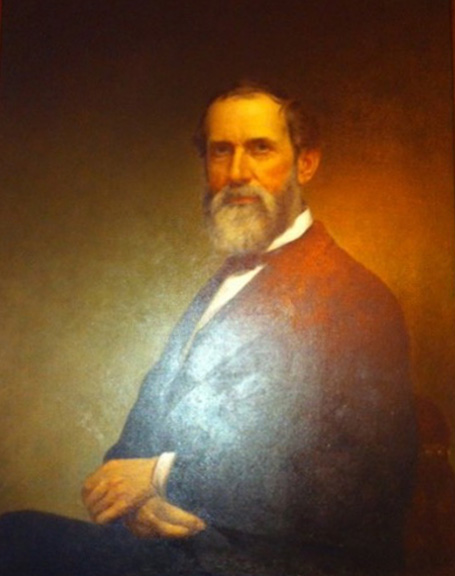

JOHN THOMAS METCALFE, M.D. (1818 – 1908)

The professor who originated the Metcalfe Prize during the Civil War was in fact a Southerner, born in 1818 in Natchez, Mississippi. For many years, he was one of the leading practitioners and most eminent consultants and medical teachers of New York.

The son of a physician, he was graduated at West Point in 1838, where he had as a classmate General P.T. Beauregard. He was, for a time, Lieutenant in the Artillery Service, but was soon transferred to the Ordnance Department. He served in the army two years, then resigned and began the study of medicine at the Jefferson Medical College, Philadelphia, from which he was graduated in 1843. After graduation he studied in the schools of Dublin, Edinburgh, Vienna, and Paris, and then returned to practice his profession in New York. On returning home he quickly took and held and that without much apparent effort, a place in the very front rank of medical practitioners in the city of New York.

For a number of years Dr. Metcalfe was professor of clinical medicine at the College of Physicians and Surgeons and his lectures both at the college and at Bellevue hospital were among the most popular given in New York. While he was idolized by his classes, he was not less beloved and esteemed in the community at large and his genial presence, his delightful humor and rare urbanity of manner, as well as his brilliant professional attainments, were said to “long dwell in the minds of all who knew him.”

He was prominent as a teacher and expounder of medicine in college and medical society. He lectured for many years at the College of Physicians and Surgeons, and to the end held the post of emeritus professor of clinical medicine there.

His resume is quite impressive:

U.S. Military Academy at West Point, 1838; 2nd Lieut., resigned 1840. Graduated in Medicine at the University of Pennsylvania, 1843. Physician near Natchez, Mississippi 1845‑1846 and in New York City, since 1846. Attending Physician to Bellevue Hospital, 1847‑1859 and Consulting Physician since 1859. Inspector of Public Schools, New York side, 1847‑1848. Physician to New York Hospital for Lying‑in Women, 1850‑1860. Consulting Physician to the New York Deaf and Dumb Institution, since 1851, to St. Luke’s Hospital, since 1853 and to Children’s Nursery and Hospital, 1855‑1860. Attending Physician to the New York City Hospital 1857. Consulting Physician to same, 1859. Consulting Physician to Bellevue, St. Luke’s, Roosevelt and Women’s Hospital, N. Y.; Professor of Institutes and Practice of Medicine in the Medical Department of the University of the City of New York, 1856‑1866 and Clinical Medicine in the College of Physicians and Surgeons, New York 1866. Author of various papers on Medical Science, 1845‑1887.

(From Dr. Michael Echol’s website medicalantiques.com)

COLUMBIA COLLEGE OF PHYSICIANS AND SURGEONS

The Columbia University Vagelos College of Physicians and Surgeons dates back more than 250 years, to 1767, when Columbia University, then only a 13-year-old college known as King’s College, established a medical faculty. The medical faculty was created two years after the University of Pennsylvania started a medical faculty, but Columbia’s medical school was the first in the American Colonies to grant the M.D. degree, in 1770.

The location of the medical college changed over the years, as did the building itself. By 1856 it was located on Crosby Street and looked like this:

In order to graduate from the medical college, candidates needed to meet the necessary requirements:

BELLEVUE HOSPITAL

Bellevue Hospital is the oldest public hospital in the United States. It was established on March 31, 1736, and is still in operation to date. It had a humble beginning as the hospital department for the New York City Almshouse.

In the days of New Amsterdam (a colony at the southern tip of Manhattan Island), the indigent poor were under the care of the church. Funds for their support came from voluntary contributions to the alms boxes, and those that had no homes were sheltered in a special house rented for that purpose, known as the “poorhouse”. At this time, the infant city only had a population of 1000, and in 1658 a small hospital was erected next to the poorhouse, representing the first hospital built on U.S. soil. By 1691, the church fund was increased by an appropriation of the public treasury, and the first “Overseer of the Poor” was established.

By 1731, the city had a population of 8628 with 1400 houses, and a considerable number of poor “vagabonds and idle beggars”. This situation fostered crime and bred sickness, and when a smallpox epidemic raged through the city that year, it became apparent that measures needed to be taken for the good of the public. Accordingly, in 1735, construction began on a stone building called the “Publick Workhouse and House of Correction of the City of New York.”

Completed in 1736, it had a footprint of just over 1300 square feet, a cellar, and was two stories high. Rooms at one end of the cellar were used to house those put at hard labor, a room at the opposite end contained a cage for refractory or dangerous criminals. Part of the building served as living quarters for the keeper and his family, but a large room at one end of the second floor was set aside as an infirmary, and contained six beds. The first medical officer was Dr. John Van Beuren; he received a salary of 100 pounds a year, out of which he was expected to supply his own medicines. Under this one roof were confined the maniac and the unruly, the poor, the aged, and the infirm. Such was the primitive beginning of Bellevue Hospital.

By 1746, extensive additions of considerable size were built onto the existing structure, but its function, as a combined poorhouse, workhouse, hospital and correctional facility remained. After the Revolutionary War, the number of poor in the city increased, and several outbuildings were raised to increase the accommodation.

From 1794 – 1805, there were annual epidemics of yellow fever in the city. Carried by mosquitoes, the poorer sections of the city, along the waterfront, were hotbeds of the plaque. Filth piled in the unpaved streets and gutters, and sewers were open canals that carried waste and refuse to the river. The outbreaks of yellow fever created the necessity of providing some place for isolation of those infected. In 1794, the worst year of the epidemics, it was decided that the most eligible area for quarantine was a five acre property and mansion on the East River owned by Brockholst Livingston, and the city purchased the lease. That land had originally been part of the old Kip’s Bay Farm, and during successive ownership, was called “Belle View”, which Livingston changed to “Belle Vue”. Belle Vue served as the city’s quarantine center until 1811, when the city decided to open a larger, more proper hospital on the East River site. Four years later, what was then called the Bellevue Establishment opened on an expanded site that totaled 28 acres. Enclosed within a 10-foot-high stone wall were numerous buildings, including a school, morgue, bake house, three-story penitentiary, greenhouse, almshouse, ice house, carpentry shop, pest house (the quarantine), and, of course, the hospital proper.

Over the succeeding decades, the hospital grounds were expanded to include the university medical college, a lumberyard, mineral water manufactory, coal yard, new morgue, etc. In 1909 the architects McKim, Mead and White designed three, non-story pavilions to replace the old buildings, and construction finished in 1939. But the complex remained as shown above, on the waterfront of the East River.

After World War II, Bristol, England, which had been savagely bombarded by the Luftwaffe, became a major port for American ships delivering supplies to England. After unloading their cargo, the ships used the dirt and rubble from Bristol’s destroyed buildings as ballast for their return home. They emptied the ballast along the edge of the East River in front of the Bellevue complex, and the thousands of tons dumped there became landfill upon which was built the East River (now FDR) Drive. By the mid-1950s, Bellevue Hospital was a complex of about 15 buildings with 2,670 beds and an average daily population of about close to 10,000. Its grounds included a post office, a state court (for commitment hearings of psychiatric patients), two public schools, a prison, several libraries, three chapels, and a mortuary. A master plan drafted in 1957 called for the replacement of almost every existing brick building, and in 1973 a gleaming 25-story, $160 million tower was completed on the eastern part of the grounds near the FDR Drive.