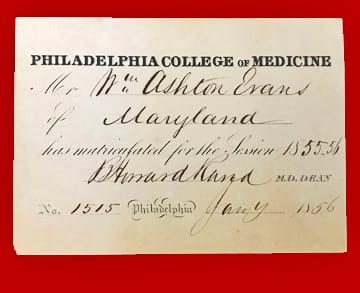

FROM THE PHILADELPHIA COLLEGE OF MEDICINE

ISSUED TO DR. WILLIAM ASHTON EVANS

HIS NEPHEW WAS A FAMOUS “ALIENIST”

This set of three medical lecture tickets and one matriculation ticket are signed by the professors who taught the course, or in the case of the matriculation ticket, the Dean of the school. They are uncommon, since they were issued by the now-defunct Philadelphia College of Medicine which was only in existence for 21 years, from 1838 – 1859. While not as elaborate, cards from the Philadelphia College of Medicine (and Pennsylvania Medical College) are much less commonly found than those of the much larger University of Pennsylvania School of Medicine.

THE HISTORY OF MEDICAL LECTURE TICKETS

When formal medical education began in North America in the 1760s, students were required to purchase tickets to attend a course of faculty lectures. Medical schools were proprietary in nature, with the faculty comprised of independent entrepreneurs who directly collected fees from students, practicing doctors, and apprentices, and then issued admission tickets to lectures.

For more than a century, medical faculty in the United States and Canada ran the medical schools. The faculty controlled who was admitted into their programs, the school’s curriculum, and its standards for graduation. At both private and university-affiliated schools, professors earned their wages from the ticket sales, after paying the school for costs to rent the classroom or lecture hall. Typically in the early and mid 1800’s, medical school was only for two years and students would buy tickets for the courses they needed to graduate.

The process was not only straightforward, but flexible. At many schools, medical students would pay a matriculation (akin to enrollment) fee to the school, then take the matriculation card to each professor to purchase lecture tickets. The student would approach several professors across campus, and pay fees to receive tickets that admitted them to courses. If they left for a year, when they returned, they could buy just the ‘tickets’ they needed to complete their degree. At the beginning of each year, the students would buy a set of lecture tickets from the various lecturers/doctors to cover the requirement for that year. Each year they bought another set of tickets toward their degree, but typically it was for a two year program.

But not everyone who attended or bought a ‘ticket’ was there to graduate. Some just attended or ‘audited’ the course to update their education. In some cases, a student may have previously graduated or attended a medical school and the course would be taken as a refresher or extended knowledge course.

Handwritten, the lecture tickets included the date of the presentation, the student’s name, and the name of the course. Many faculty members signed their names on the front or back of the cards, although not all schools required this. The student’s signature is always on the front of the card. The earliest tickets were often written on plain paper cards. In later years, the tickets were printed from engraved plates. Tickets from the late 18th century and early 19th century show the influence of neo-classical design in ribbon and fretwork borders. Drawings of buildings on the campus are not uncommon. Anatomy professors presented some of the more graphic tickets, which might include an image of a skull or dancing cadavers.

After the Civil War college-level courses became more structured and organized across the whole country, due to the need to standardize medical education. The lecture ticket system was discontinued in the late 19th century after medical schools began paying a flat salary to professors.

WILLIAM ASHTON EVANS, M.D. c. 1832 – 1865

Dr. Evans was born about 1832 in Pennsylvania (probably Philadelphia). He was the son of Colonel Britton Evans, who was of Welsh descent. Col. Evans was an officer in the Regular Army for nine years, beginning during the War of 1812 at which time he was commissioned a Lieutenant of Artillery and served under General Harrison. He served in the battles of River Raisin (Frenchtown) and at another in which Tecumseh was killed. He also served in the Florida Seminole War. After the massacre at the Alamo in March of 1836, he was recalled to service and appointed as Adjutant General to the Army of Texas. Two months later, at his hometown of Philadelphia, a group of Texan sympathizers formed a company under Colonel Evans and joined the army of General Sam Houston. After his retirement from active service, he served as a Justice of the Peace in Philadelphia and Colonel of the State Troops. He fathered nine children, and of his five sons, three were physicians.

William Ashton’s older brother, Louis W. Evans, born in 1818, graduated from two medical schools in Philadelphia and practiced there for some years before moving to Maryland. Louis’s son, Britton Duroc Evans, also became a physician with a keen interest in mental illness, and was ultimately in charge of the New Jersey State Hospital. He was also an “alienist” and was renowned as an expert in the medico-legal aspects of insanity. He served as a defense witness, testifying on behalf of Harry Thaw in his trial for the 1906 murder of Stanford White (Thaw was found “not guilty” by reason of insanity).

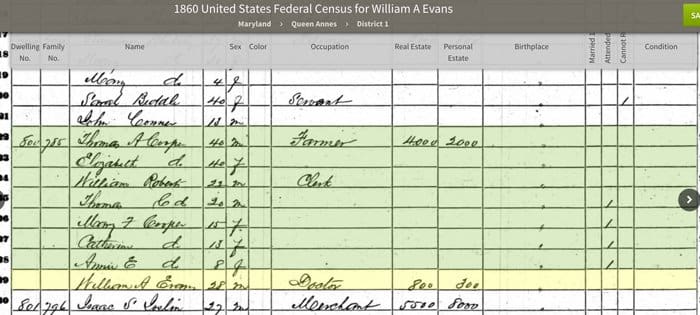

Unfortunately, very little about William Ashton Evans’ short life can be found. Presumably, he went to medical school and obtained his medical degree in Philadelphia. He was single, aged 28, and a “doctor”, when living with a family in Templeville, Maryland in the 1860 census.

In 1863, when he registered for the Civil War draft in Templeville, he stated he was born in Pennsylvania, gave his age as 32 and his occupation as physician.

The last information found was a snippet in the May 1865 edition of the Philadelphia Medical and Surgical Reporter, which simply confirms his death: “In Templeville, Md., May 6, Wm. Ashton Evans, aged about 30 years.”

THE PHILADELPHIA COLLEGE OF MEDICINE, 1838 – 1859

The Philadelphia College of Medicine had its origins in the Philadelphia School of Anatomy, which was established by James McClintock in 1838. In 1847 McClintock obtained a charter from the Pennsylvania Legislature to establish the Philadelphia College of Medicine. He had organized the school in 1846, holding classes that winter and summer in the building of the Philadelphia School of Anatomy on Filbert Street above Seventh Street. With the charter, McClintock’s school had the power to confer degrees to students. The year the charter was obtained, the College moved to new facilities at Fifth and Walnut Streets which had originally been constructed for the Supreme Court of Pennsylvania, known as the Adelphi Building.

Built in 1829 – 1830, the building was the scene of the American Anti-Slavery Society three day organizational meeting on December 4, 1833. From 1834 – 1835, it was occupied by the Philadelphia Club, then the Odd Fellows Hall in 1845. It was home to the Philadelphia College of Medicine from 1846 – 1859. The five story building contained two lecture rooms, an anatomical theater, a museum, a dissecting room, classrooms, and rooms for professors. In addition, the College included a pharmacy department to instruct advanced students. Students had access to Pennsylvania Hospital, Wills Hospital, and the Philadelphia Dispensary for clinical instruction. In 1847, the surgical amphitheater was added, and the client for the construction was listed as James McClintock, M.D., then dean and professor of Principles and Practice of Surgery.

The full period of study was the same as that offered in other colleges, with the difference that two courses of lectures were delivered annually, instead of one. One was called the “Winter Course” and commenced in October, the other was the “Spring Course” and commenced about a week after the close of the first, or about the first week of March. This was done to ensure that the course of instruction, and access to the necessary facilities, were equally full in the spring as the winter.

At its first commencement in 1847, eighteen students graduated. From 1847 to 1854 about four hundred students were graduated. In the latter year the college was reorganized, and adopted the code of ethics of the American Medical Association.

By 1858 the College was experiencing financial difficulty, and reached an agreement with the Medical Department of Pennsylvania College by which the two schools would merge in 1859. After the merger, the faculty of the Philadelphia College of Medicine became the faculty of the Pennsylvania Medical College, with Dr. Lewis D. Harlow as dean. Many of the Medical Department ended up resigning, and the faculty of the Philadelphia College assumed the name and operated as the Medical Department of Pennsylvania College. Eventually that institution closed in 1861.

THE MEDICAL PROFESSORS WHO SIGNED THE COURSE TICKETS

(Note: The information below is taken from Dr. Michael Echols’ superb site, www.medicalantiques.com)

Perhaps the most interesting thing about these particular cards are that each of the physicians who signed them had service in, or association with, the Civil War – one, Dr. George Hewston, performed medical aid to some members of the Sixth Massachusetts Infantry injured in the “Baltimore Riots”, which was the first hand-to-hand skirmish of the Civil War.

LEWIS D. HARLOW, M.D. (1818 – 1895)

Dr. Harlow, a native of Vermont, graduated from the University of Pennsylvania School of Medicine, Philadelphia, 1845. He died of heart disease in in 1895, in Philadelphia.

During the Civil War, he was stationed at U. S. A. Hospital Corps, Fourth and George Streets, Philadelphia. Dr. Harlow was Surgeon in charge of this Philadelphia hospital and later was promoted to Surgeon of U.S. Volunteers. Harlow was a full surgeon with the U.S.V. and spent time in Nashville and Chattanooga during the Civil War. Surgeon Lewis D. Harlow, U.S.V. has been relieved from duty at General Hospital No. 8, Nashville, Tenn., and assigned to General Hospital No. 8, Chattanooga, Tenn.

Medical and Surgical History citations for Dr. Harlow:

CASE 1320.–Colonel G. Mihalotzy, 24th Illinois, was wounded at Tunnel Hill, February 25, 1864. Surgeon L. D. Harlow, U. S. V., reported from the Officers’ Hospital, Lookout Mountain: “A deep gunshot flesh wound of the right arm above the elbow. Haemorrhage, amounting to sixteen ounces, from the anastomotica magus, took place on March 2d. Solution of perchloride of iron was applied. The patient died March 11, 1864, probably from pyaemia which succeeded the haemorrhage.”

CASES 1715-1730.–1. Lt. W. M. Begole, Co. H, 23d Michigan, wax wounded at Lost Mountain, June 16, 1864. Surgeon E. Shippen, U. S. V., Medical Director of the Twenty-third Corps, reported from the field a “severe gunshot wound of the left shoulder.” At the Officers’ Hospital, at Chattanooga, Surgeon L. D. Harlow, U. S. V., reported: ” The ball grazed the humerus and emerged near the axilla. Haemorrhage occurred, August 30th, from the superior thoracic, with loss of twelve ounces of blood. The bleeding was arrested by compression and application of solution of persulphate of iron. Haemorrhage recurred, and death resulted October 15, 1864.”——2. Pt. A. Brown, Co. D, 64th New York, aged 26 years, was wounded at Hatchet’s Run, March 25, 1865, by a minié ball.

Dr. Harlow, a native of Vermont, graduated from the University of Pennsylvania School of Medicine, Philadelphia, 1845. He died of heart disease in in 1895, in Philadelphia.

During the Civil War, he was stationed at U. S. A. Hospital Corps, Fourth and George Streets, Philadelphia. Dr. Harlow was Surgeon in charge of this Philadelphia hospital and later was promoted to Surgeon of U.S. Volunteers. Harlow was a full surgeon with the U.S.V. and spent time in Nashville and Chattanooga during the Civil War. Surgeon Lewis D. Harlow, U.S.V. has been relieved from duty at General Hospital No. 8, Nashville, Tenn., and assigned to General Hospital No. 8, Chattanooga, Tenn.

Medical and Surgical History citations for Dr. Harlow:

CASE 1320.–Colonel G. Mihalotzy, 24th Illinois, was wounded at Tunnel Hill, February 25, 1864. Surgeon L. D. Harlow, U. S. V., reported from the Officers’ Hospital, Lookout Mountain: “A deep gunshot flesh wound of the right arm above the elbow. Haemorrhage, amounting to sixteen ounces, from the anastomotica magus, took place on March 2d. Solution of perchloride of iron was applied. The patient died March 11, 1864, probably from pyaemia which succeeded the haemorrhage.”

CASES 1715-1730.–1. Lt. W. M. Begole, Co. H, 23d Michigan, wax wounded at Lost Mountain, June 16, 1864. Surgeon E. Shippen, U. S. V., Medical Director of the Twenty-third Corps, reported from the field a “severe gunshot wound of the left shoulder.” At the Officers’ Hospital, at Chattanooga, Surgeon L. D. Harlow, U. S. V., reported: ” The ball grazed the humerus and emerged near the axilla. Haemorrhage occurred, August 30th, from the superior thoracic, with loss of twelve ounces of blood. The bleeding was arrested by compression and application of solution of persulphate of iron. Haemorrhage recurred, and death resulted October 15, 1864.”——2. Pt. A. Brown, Co. D, 64th New York, aged 26 years, was wounded at Hatchet’s Run, March 25, 1865, by a minié ball.

WILLIAM A. BRADLEY, M.D. (1831 – 1869)

Dr. Bradley was born in the District of Columbia. He was appointed Assistant Surgeon United States Army on October 22, 1861 and was on duty with the Army of the Potomac, to December, 1862. Assigned to Hospital duty, Washington, D. C., to February, 1864, then to the Medical Director’s Office, Department of Washington, to June, 1868. He was made Brevet Captain and Major U. S. Army, for faithful and meritorious services during the war. He was stationed at Point San Jose, California, from June 1868 to his death there in February 1869. The Register of Death for the Regular Army lists his cause of death as “apoplexy.” He is buried in Glenwood Cemetery in the District of Columbia.

Medical and Surgical History citations for Dr. Bradley:

CASE 435.–Private S. C. Gage, Co. C, 15th New Jersey, aged 28 years, was admitted to Finley Hospital, Washington, May 8, 1863, with a gunshot penetrating wound of the chest and abdomen, received at Chancellorsville on the 3d. A conoidai musket ball had entered at the right side between the seventh and eighth ribs, nearer to the spine than to the sternum. Its course was inward, upward, and forward; and its exit two and a half inches to the inner side of the right nipple, between the fourth and fifth ribs. The liver was wounded in its passage as well as a portion of the lung. Bile was discharged for several days from the lower or entrance wound. On May 12th, at eleven o’clock at night, uncontrollable haemorrhage occurred, and death resulted in a short time, May 13, 1863. Assistant Surgeon William A. Bradley, U. S. A., reported the case.

CASE 564.–Private Lewis Vetter, Co. I, 1st New York Artillery, aged 32 years, was wounded at Chancellorsville, May 3, 1863. He remained at the field hospital until the 7th, when he was transferred to Finley Hospital, Washington. Here, Assistant Surgeon William A. Bradley, U. S. A., recorded the injury as a “shot wound of the right side.” On June 2d, the man was transferred to Satterlee Hospital. The following notes of the case appear upon the case-book: “Gunshot wound of the anterior wall of the abdomen; the ball entered about one inch above the crest of the right ilium. The patient states that a portion of omentum protruded about six inches from the wound, and that the protrusion was tied arid replaced. The ligature still remains. Sulphate of copper dressings. June 16th, traction on the ligature was commenced by adhesive, strips, and water dressings were applied to the wound. On the 18th, the ligature came away. The patient had some diarrhœa on the 19th. On the 20th, cerate dressings were applied.” The case appears to have progressed favorably, and on July 27th Vetter was returned to duty. He is not a pensioner.

When first placed as medical officer at this post, I found much tendency to Diarrhea and milder forms of dysentery, produced by the use of the river water, which holds both lime and magnesia in solution. This source of trouble has been remedied for the future by having a well sunk in one of the bastions, which it is believed will afford a sufficient quantity of purer water, though its chemical constituents have not yet been ascertained by analysis.

Extract from the Report of Acting Assistant Surgeon WILLIAM A. BRADLEY, Jr., U. S. A. Upton’s hill, Virginia, September 30, 1861.

GEORGE HEWSTON, M.D. (1826 – 1891)

Dr. Hewston was born in Philadelphia in 1826. He was of English and Scotch, descent, his father and mother both having been natives of Northern Ireland, of English and Scotch parentage. His father, John Hewston, was a business man of Philadelphia for many years, and died in that city in 1869, at the advanced age of eighty seven years. Dr. Hewston’s grandmother died in Philadelphia in 1851, at the age of ninety-eight years. During the storming of Fort McHenry at Baltimore by the British in the war of 1812, Dr. Hewston’s mother, then a young girl, with other ladies of Baltimore, supplied the American troops in the fort with provisions from that city, one of the ladies on an expedition being struck by a shell from one of the British ships and killed instantly.

He graduated from the Philadelphia College of Medicine in 1850 after a full three-years course of instruction, and was immediately elected Prosector of Surgery and Demonstrator of anatomy of that college. In 1853 he was elected to the Chair of Anatomy, which he held until 1858. In 1851 he commenced his private practice, continuing until moving to California in 1861. In 1860 he received, after having completed the course of study required, a further degree of Doctor of Medicine from the medical department of the University of Pennsylvania.

Dr. Hewston was, from 1851 to 1860, one of the surgeons of the Philadelphia Fire Department, and in April 1861, dressed the wounds of some members of the Sixth Massachusetts Infantry Regimental Band who were wounded while passing through Baltimore on their way to Washington, in an incident known as the “Pratt Street” or “Baltimore” Riot. (Some of the militia walked back to Philadelphia and apparently it was some of the band members among this group who were treated by Dr. Hewston in Philadelphia.)

He moved to California in 1861 “to escape the Civil War” (as it is noted in Wikipedia), and resided and practiced medicine in San Francisco. Hewston established a new medical practice upon his arrival, supplementing his income by lecturing at the Toland College of Medicine (later UCSF. He was for seven years Surgeon on the staff of Major General Allen, commanding the State Militia from 1863 to 1870. His skill at lecturing brought him to the attention of the People’s Party, which nominated him for Supervisor and in 1873 he was elected one of the Board of Supervisors. He was appointed Mayor in 1875 and served 30 days, to finish James Otis’s unfinished term.

During his brief term, Hewston sat in on an investigation into charges against six policemen. He also refused to make inflated payments for unspecified repairs. He was known for making a speech condemning the Chinese for bringing opium into the city.

In 1876 he was appointed by the commissioners of the Centennial Exposition as one of the Board of Judges for the International Centennial Commission of 1876. His final political activity was as chair of the Anti-Monopoly Party, which sought to stop the transfer of federal lands for the railroads.

Hewston was a fluent speaker, and delivered many brilliant, scientific and medical public lectures. In later years he returned to the lecture circuit and traveled along the East Coast, collecting many books along the way. He eventually amassed some 2000 volumes for his private library.

He died in San Francisco in 1891 of Bright’s Disease (acute or chronic nephritis).