This is a group of five medical college tickets to lectures at the Medical Institution of Yale College. One card is for a lecture in the 1843 – 44 session, four of the cards are for the 1844-45 session, and one card attests to matriculation from the college. All were purchased by Dr. Edward McEwen Beardsley (1823 – 1905). Each of the tickets are signed by the professor, and are to the following lectures:

“Surgery” – 1843 – 44 session – lecture given by Dr. Jonathan Knight

“Obstetrics” – 1843 – 44 session- lecture given by Dr. Timothy Phelps Beers

“Anatomy and Physiology” – 1844 – 45 session – lecture given by Dr. Charles A. Hooker

“Obstetrics” – 1844-45 session – lecture given by Dr. Timothy Phelps Beers

” Materia Medica” – 1844-45 session – lecture given by Dr. Henry Bronson

“Theory and Practice of Physic and Diseases of Children” – 1844-45 session – lecture given by Dr. Eli Ives

One matriculation card for the 1844-45 session, signed by Dr. Charles A. Hooker.

DR. EDWARD MCEWEN BEARDSLEY (1823 – 1905)

Dr. Beardsley was born in Danbury, Connecticut, the son of Samuel Birdseye Beardley and Abigail McEwen. His father, who was a 1815 graduate of Yale College, was a teacher in a select school in Monroe, Conn. Edward assisted his father in teaching until he entered the Medical Institution of Yale Colleg, from which he graduated in 1845, his doctoral thesis being on “Puerperal Fever”.

After graduation he was in the drug business in New Haven, and then combined teaching in his father’s school (where he was principal for twenty years), and the practice of medicine until 1861, after which he devoted himself entirely to his medical practice until suffering a paralytic stroke in 1903.

In 1855 he married Elizabeth A. Gray, and they had seven children. In 1879 and 1880 he was a member of the Connecticut House of Representatives, in which he served on the committee on foreign relations.

He died of paralysis at his home in Monroe on March 11, 1905, at the age of 82.

THE HISTORY OF MEDICAL SCHOOL LECTURE TICKETS

When formal medical education began in North America in the 1760s, students were required to purchase tickets to attend a course of faculty lectures. Medical schools were proprietary in nature, with the faculty comprised of independent entrepreneurs who directly collected fees from students, practicing doctors, and apprentices, and then issued admission tickets to lectures.

For more than a century, medical faculty in the United States and Canada ran the medical schools. The faculty controlled who was admitted into their programs, the school’s curriculum, and its standards for graduation. At both private and university-affiliated schools, professors earned their wages from the ticket sales, after paying the school for costs to rent the classroom or lecture hall. Typically in the early and mid 1800’s, medical school was only for two years and students would buy tickets for the courses they needed to graduate.

The process was not only straightforward, but flexible. At many schools, medical students would pay a matriculation (akin to enrollment) fee to the school, then take the matriculation card to each professor to purchase lecture tickets. The student would approach several professors across campus, and pay fees to receive tickets that admitted them to courses. If they left for a year, when they returned, they could buy just the ‘tickets’ they needed to complete their degree. At the beginning of each year, the students would buy a set of lecture tickets from the various lecturers/doctors to cover the requirement for that year. Each year they bought another set of tickets toward their degree, but typically it was for a two year program.

But not everyone who attended or bought a ‘ticket’ was there to graduate. Some just attended or ‘audited’ the course to update their education. In some cases, a student may have previously graduated or attended a medical school and the course would be taken as a refresher or extended knowledge course.

THE MEDICAL INSTITUTION OF YALE COLLEGE

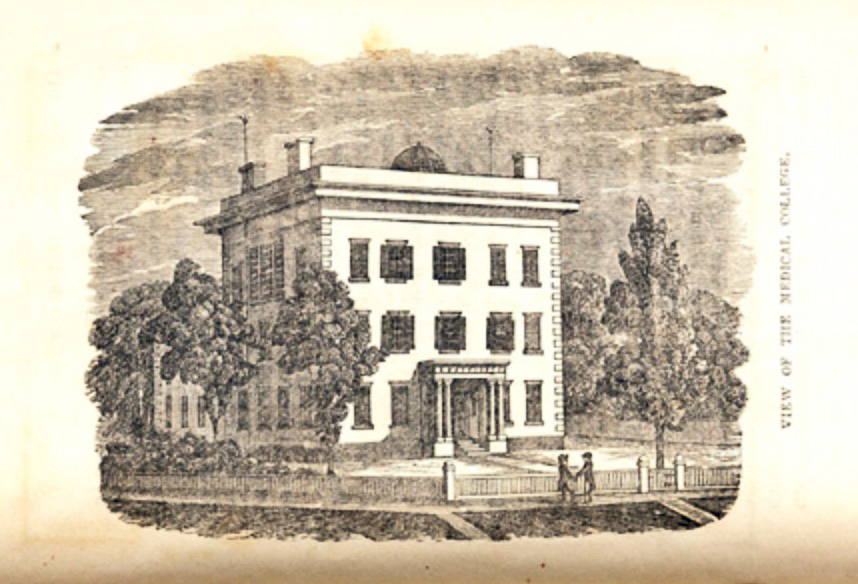

The Medical Institution of Yale College was America’s sixth medical school. It was chartered in 1810 and opened in 1813, as a joint project of Yale and the Connecticut Medical Society. This relationship to the state society was unusual among medical colleges and proved beneficial to the college in its early years. Classes were held and students were housed at a building on the corner of Grove and Prospect Streets across the street from the Grove Street Cemetery. The building was originally built as a hotel. At first the building was rented, but a grant from the State Legislature enabled Yale to purchase it.

The medical school flourished in its first decades especially due to the reputations of Nathan Smith, Professor of the Theory and Practice of Physic and Surgery, and Benjamin Silliman, Professor of Chemistry. Yale required higher standards of preliminary education for admission than did other medical schools, hurting enrollment when a boom in medical schools that started in the 1830s increased competition for students. Yale was also atypical in that it fixed the price of professors’ lecture tickets to be no more than $12.50.

THE MEDICAL PROFESSORS WHO SIGNED THE COURSE TICKETS

Note: In the process of researching these tickets, I found out, rather unsurprisingly, that two of the professors had each been taught by the third, and oldest, professor – Dr. Eli Ives.

ELI IVES, M.D. (1779 – 1861)

AMERICA’S FIRST ACADEMIC PEDIATRICIAN

Dr. Eli Ives was the son of Dr. Levi and Lydia Ives, and was born in New Haven, Connecticut in 1779. He graduated from Yale University in 1799. After graduation, he spent two years as Rector at Hopkins Grammar School while studying medicine partly with his father. He later attended medical lectures given in Philadelphia by Dr. Benjamin Rush and Dr. Caspar Wistar, but did not complete the medical degree. In 1801, he began the practice of medicine in New Haven, which he continued for fifty years, eventually achieving renown throughout the state. The Connecticut Medical Society awarded him an honorary M.D. in 1811. In 1805 he married Maria Beers, the daughter of Deacon Nathan Beers, and they had three sons and two daughters.

Ives helped establish Yale’s medical school in 1813, and was one of four original professors, teaching Materia Medica. He held the Chair of Materia Medica and Botany for sixteen years until 1829, when he was transferred to the Chair of the Theory and Practice of Medicine and Diseases of Children (which card shown bears his shaky signature.) In this capacity, he delivered the nation’s first systematic pediatrics course and held the earliest American academic appointment in pediatrics. Beardsley was fortunate to take this course during his interlude at Yale.

In 1853, Ives ceased to be actively engaged in lecturing and was made Professor Emeritus. In 1860 he was elected president of the American Medical Association. He was one of the founders of the New Haven Medical Association and a member of the Connecticut State Medical Society. The American Medical Association elected him President in 1860. He died in 1861 at the age of 82.

TIMOTHY PHELPS BEERS, M.D. (1789 – 1858)

Dr. Beers was born in 1789, the second son of Deacon Nathan Beers and his wife, Mary Phelps. One of his sisters married Dr. Eli Ives (see above). He began the study of medicine under his brother-in-law in New Haven, and in the winter of 1811-12 attended medical lectures at the University of Pennsylvania, in Philadelphia.

In 1812, he began the practice of medicine in New Haven. In 1813 he accepted duty as Surgeon of a regiment of militia, and was stationed in New London for several months. In 1824, he was awarded the honorary degree of M.D. by Yale College, on the recommendation of the State Medical Society. In 1830 he was appointed a Professor in the Medical Institution of Yale College, and filled the Chair of Obstetrics until his resignation in 1856. It was while he was in this capacity that Beardsley attended his lecture.

He died in 1858 after a “brief but distressing illness of one week, from a disease of the kidneys” in New Haven, in his 69th year of age.

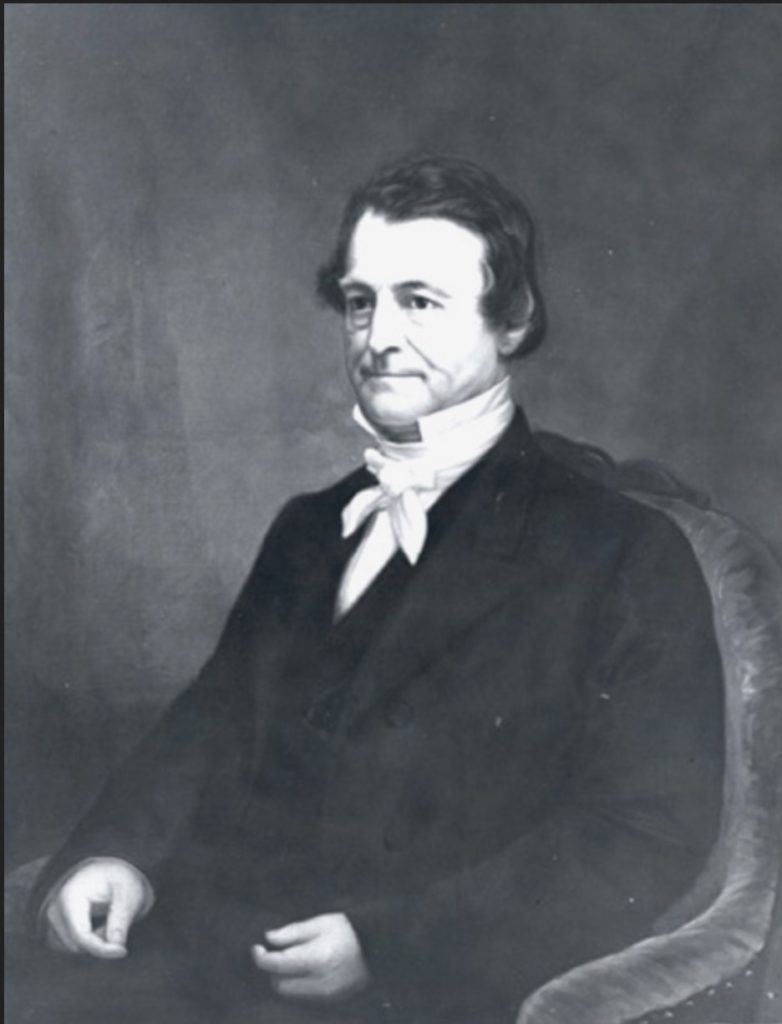

JONATHAN KNIGHT, M.D. (1789 – 1864)

One of the founding professors of the Medical Institution of Yale College, Knight was the son of Dr. Jonathan Knight, a Surgeons Mate in the Continental Army. He was graduated from Yale College in 1808, and for two years after graduation, taught school for two years before attending two medical lectures at the University of Pennyslvania. He was licensed to practice by the Connecticut Medical Society in 1811, and received the honorary degree of M.D. from Yale College in 1818.

When the Medical Institution of Yale College was organized in 1813, he was appointed the Professor of Anatomy and Physiology. he continued in this post for 25 years, when he was transferred to the Chair of Surgery. After lecturing for fifty years to successive classes of students, he resigned all connection with the college in 1864.

During all this time, he had maintained an active private practice, and in 1846 and 1847 was President of the convention which formed the American Medical Association, and then President of the Association itself, in 1853.

He died in New Haven, just short of his 75th birthday. The Knight Hospital of the U.S. Government in New Haven, now the Yale-New Haven Hospital, was named in his honor.

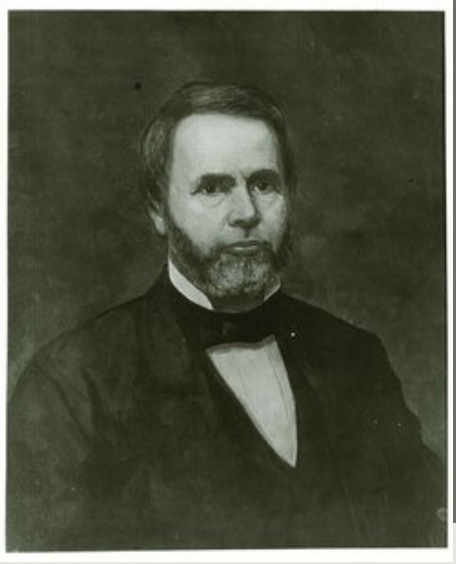

CHARLES A. HOOKER, M.D. (1799 – 1863)

PROFESSOR AND FIRST DEAN

Charles Hooker, a descendant of Rev. Thomas Hooker, the first minister of Hartford, became Professor of Anatomy and Physiology in 1838 when Jonathan Knight transferred to the Chair of Surgery. In 1845, Hooker became the medical school’s first dean, although the Yale Corporation did not officially appoint him to this office until 1853.

Hooker had attended Yale College, studied medicine under Eli Ives as preceptor, and received his M.D. from Yale in 1823. His medical practice in New Haven, which grew quite extensive, included surgery, obstetrics, and practical medicine. He acquired a reputation for being a heroic practitioner because he often gave large doses of remedies. One of the earliest to use auscultation to study and diagnose diseases of the intestinal canal, Hooker was able to hear the distinctive sounds of cholera, a disease he treated with calomel. His memorialist wrote of him, “Dr. Hooker was an enthusiast in his profession, he loved it ardently and devoted all the energies of his mind to the development of its resources.”

HENRY BRONSON, M.D. (1804 – 1893)

Dr. Bronson was born in Waterbury Connecticut in 1804, the second son of Judge Bennet Bronson (Yale, 1797) and Anna Smith. Judge Bronson was a lawyer and County court judge, as well as a large landed proprietor, and so a man of much wealth and influence. He had already sent Henry’s older two brothers to Yale, but both died young – and it was his wish that Henry settle at home and take charge of his estate.

Henry’s interests lay along more intellectual pursuits, however, and in 1824 he entered himself into the Medical Department of Yale College, graduation with an M.D. degree in 1827. He settled in West Springfield, Massachusetts, and began the practice of medicine. He married Sarah Miles, daughter of a wealthy lawyer and member of congress, in 1831. Shortly after the marriage, they relocated to Albany, New York, where Dr. Bronson had accepted an invitation to join the clinical practice of Dr. Alban March, Professor of Surgery at Albany Medical College. Bronson, a man of letters, wrote scientific articles for periodicals in his leisure time.

In the summer of 1832, an epidemic of Asiatic cholera swept the country after having been brought to Quebec by passengers on a ship. Dr. Bronson was sent to Montreal to study the epidemic, its modes of transmission, etc. He remained for several weeks, writing out his observations and theories (now outmoded). Upon his return to Albany, his father persuaded him to settle in his home town of Waterbury, Conn. After ten years of a country practice, supplemented by clinical study in European hospitals, he chose an academic path, and in 1842 accepted the position of Chair in Materia Medica and Therapeutics at the Medical Institution at Yale College. With the exception of one year, he gave lectures to successive classes until 1860.

Plagued with frail health his entire life, he devoted his latter years to his other love, history, and dabbled in economics. He wrote a six-hundred page book on the history of the town of Waterbury, Connecticut, as well as a “Historical Account of Connecticut Currency, Continental Money and the Finances of the Revolution.” Revered by the medical college staff and students, he was the commencement orator for the Yale Medical Institution Class of 1863.

He died in New Haven in 1893, two months shy of his 90th birthday.