1821 -1910

Without taking anything away from Elizabeth Blackwell’s groundbreaking accomplishment, is important to note that she was not the first woman to practice medicine or to be recognized as a physician. Women have been practicing medicine, both openly and secretly, since ancient times. She was not even the first to practice in America. That distinction probably belongs to Harriot Kesia Hunt (1805-1875), who practiced openly for about 20 years in Massachusetts before being allowed to attend lectures at Harvard Medical School in 1850 and receiving an honorary M.D. from Woman’s Medical College of Pennsylvania in 1853. But by modern educational and credentialing standards, Blackwell was the first woman in the world to earn a regular M.D. degree from a regular or accredited medical school by means of satisfying the standard requirements of a full course of study – simultaneously making history and opening the door for all women to follow.

1805 – 1875

HER PARENTS’ RADICALLY PROGRESSIVE IDEAS WITH

REGARDS TO THE EDUCATION OF FEMALES

YIELDS TWO WOMEN PHYSICIANS

Elizabeth was born in 1821, in Bristol, England, one of nine children of a sugar refiner, Samuel Blackwell, and his wife Hannah. The family was very close-knit, and all felt a spirit of reform, dissent, and progressive political thinking. For example, they believed in free and equal education for both sexes, a radical notion in those days. Samuel wanted his daughters to have the same educational opportunities as their brothers, so Elizabeth and her sisters studied with private tutors, learning the same subjects as their brothers. The Blackwell children grew up surrounded by a progressive social consciousness, including support for women’s rights, temperance and the abolition of slavery. Elizabeth described her childhood as “very happy years, rich and satisfying.” Most of the children, not just Elizabeth, would later become prominent in social reform movements. Emily, her y0unger sister by 5 years, would follow in her sister’s footsteps and become the third female to earn an medical degree.

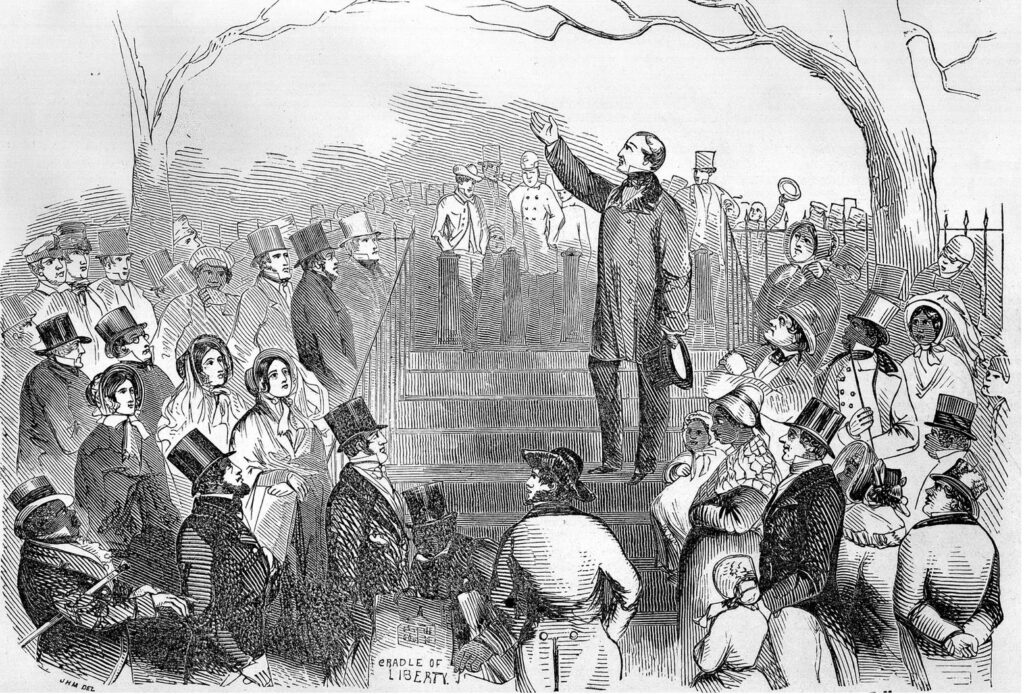

When the father’s business collapsed in 1832, the family left England to start over in America, in pursuit of business opportunities and progressive ideas. They spent the next six years in New York City and the suburbs of Long Island and New Jersey. Elizabeth attended school and threw herself into the abolitionist movement, attending anti-slavery meetings and sewing for abolitionist fundraising fairs.

Fugitive Slave Act of 1850

In 1838, when Elizabeth was 17, business prospects lured the family to Cincinnati. They were “full of hope and eager anticipation,” she wrote. But within a few months of arriving, her father died, leaving the family penniless. To support the family, Elizabeth and her sisters opened a young ladies’ day and boarding school. They closed it after a few years, and Elizabeth went on to teach in several states. By her mid-20s, Elizabeth had lived in New York, New Jersey, Cincinnati, Kentucky, North and South Carolina, and Philadelphia, mostly under adverse financial circumstances. While teaching she also studied medicine privately under Dr. Samuel Dickson in Charleston, South Carolina and Dr. Joseph Warrington in Philadelphia. Her circle in Philadelphia consisted mainly of Quaker liberals, abolitionists, and other reformers, who noticed her talent for medicine and urged her to try to break the gender barrier in that profession.

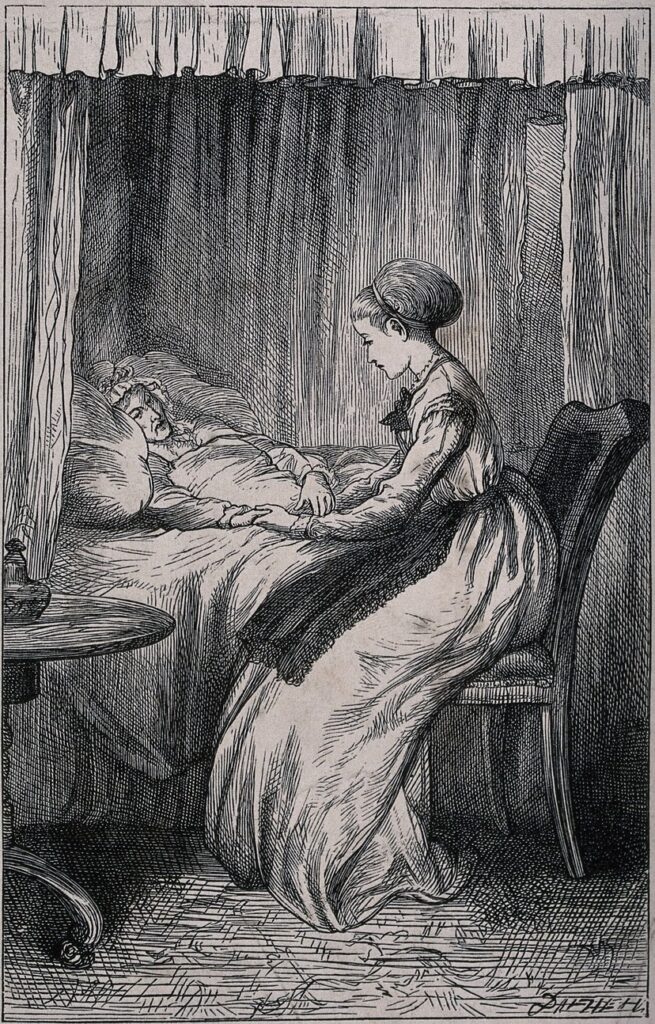

During this period, 24-year-old Elizabeth visited a close family friend dying of uterine cancer who spoke of how she had suffered at the hands of male doctors during her medical treatment. “Why not study medicine?” the friend asked. “If I could have been treated by a lady doctor, my worst sufferings would have been spared me.” Elizabeth immediately rejected the idea. “I hated everything connected with the body and could not bear the sight of a medical book,” she wrote in her autobiography. But the spark was lit.

In her 1895 autobiography, Pioneer Work in Opening the Medical Profession to Women, she records her thoughts at that seminal moment when she decided to embark on what many would have viewed as a Quixotic mission:

“My mind is fully made up. I have not the slightest hesitation on the subject; the thorough study of medicine, I am quite resolved to go through with. The horrors and disgusts I have no doubt of vanquishing. I have overcome stronger distastes than any that now remain, and feel fully equal to the contest. As to the opinion of people, I don’t care one straw personally; though I take so much pains, as a matter of policy, to propitiate it, and shall always strive to do so; for I see continually how the highest good is eclipsed by the violent or disagreeable forms which contain it.“

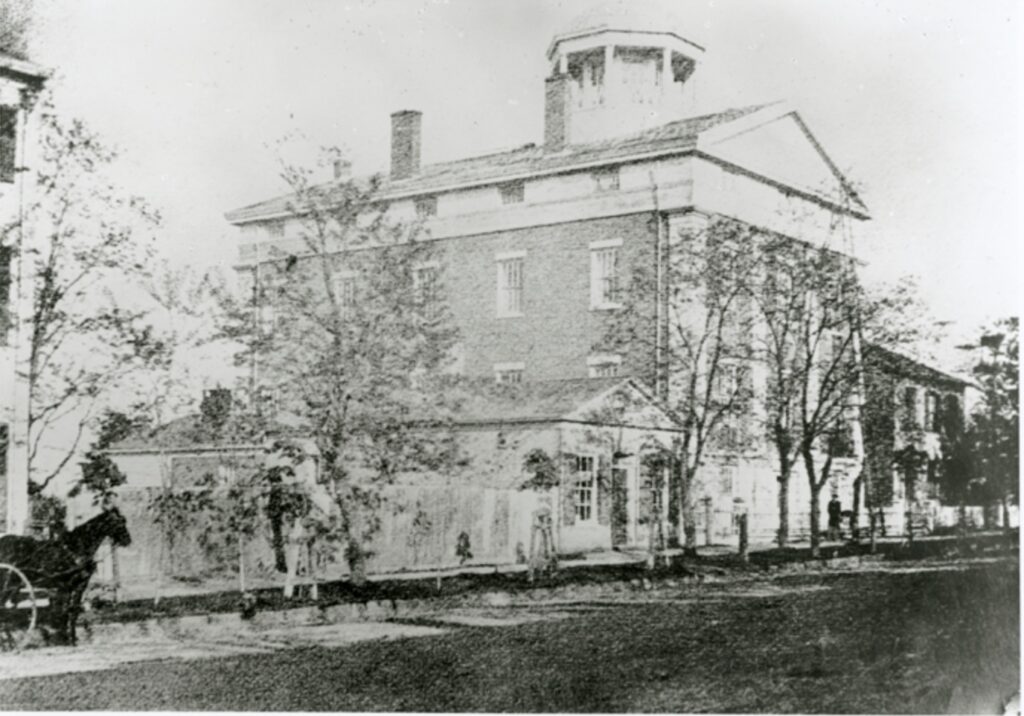

ELIZABETH GAINS ADMISSION TO GENEVA MEDICAL COLLEGE

DUE TO A JOKE THAT BACKFIRED

Physicians in Philadelphia and New York, whose advice Elizabeth sought, were uniformly discouraging. A woman had never been admitted to medical school, the time was not right, she could only succeed if disguised as a man. She applied to Yale, Harvard, and every medical school in Philadelphia but was refused admittance because of her gender. She then applied to a dozen smaller colleges. She received a single acceptance, from Geneva Medical College in upstate New York. Her acceptance was the result of a joke that backfired.

When her application reached Geneva in 1847, her rejection was a foregone conclusion. While the faculty of the Medical College did not want her, they also did not want to offend the doctor who recommended her so they put the question of Blackwell’s admission to the students, but with the stipulation that the decision must be unanimous. In one version the students thought that the faculty was joking so they joined in on the joke by voting to admit Blackwell. According to the other version, students knew that faculty were troubled about Blackwell’s application and thought it would be funny to admit a woman so they did. They achieved unanimity by beating up the lone holdout until he capitulated. The astonished faculty, against their will but bound by their word of honor, had no choice but to admit her. A few weeks later the “lady student” appeared in the lecture room.

Elizabeth arrived in Geneva on November 6, 1847, several weeks after the term had begun. Though she described her reception as friendly, there was probably an undertone of surprise and consternation among students and faculty.

At first, Elizabeth – the “lady student” – experienced the bewilderment of any new student, but the novelty of her gender made her position more difficult. During her 15 months as a student, the Geneva community treated her terribly. Doctors’ wives refused to speak to her. Townspeople stared at her as if she were an exotic animal. Many regarded her as either a lewd woman, or insane, or both, and in any event someone sure to be a bad influence on children. Curious strangers entered the lecture room to stare at her.

Her attendance at anatomy lectures produced embarrassment and the professor, Professor James Webster, her most enthusiastic supporter, suggested that she stay away on the days reproductive anatomy was demonstrated. She replied that she wished to be treated simply as another student, that she regarded the study of anatomy with profound reverence, and was certain that an experienced medical man could not feel embarrassment from her presence.

Elizabeth took her studies seriously, earned the respect of her colleagues and graduated at the top in her class.

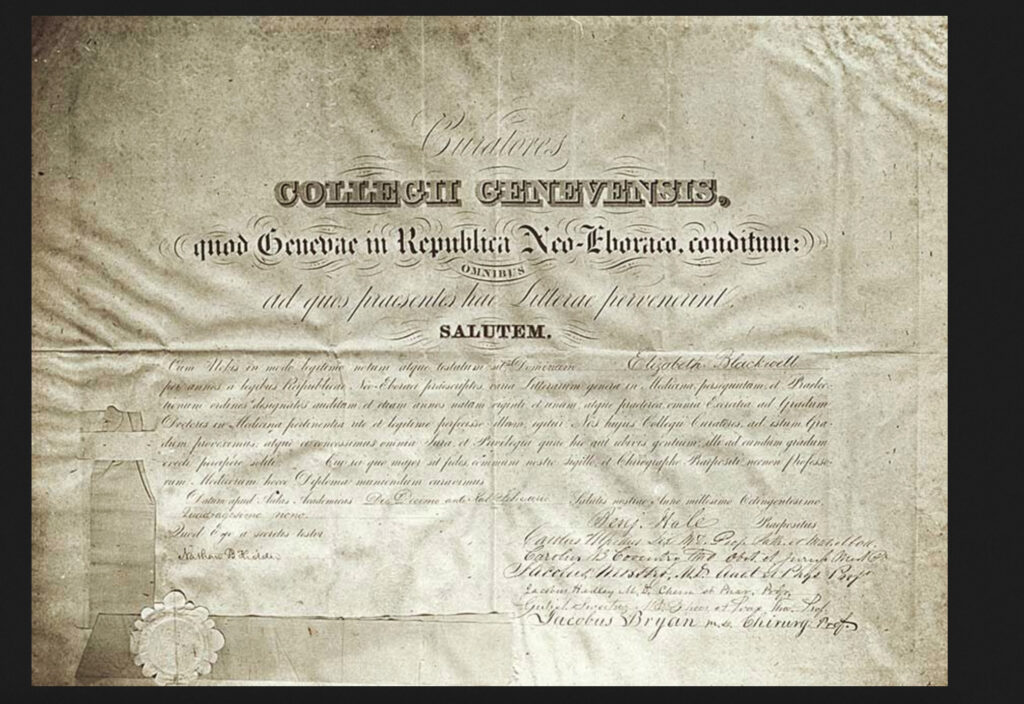

On January 23, 1849, Blackwell became the first woman to achieve a medical degree in the United States. The town turned out to the packed ceremony and fell silent when Dr. Blackwell was called up last to receive her diploma. When the dean Dr. Charles Lee, conferred her degree, he stood up and bowed to her. “It shall be the effort of my life, by God’s blessing, to shed honor on this diploma,” she said. The crowd burst into applause.

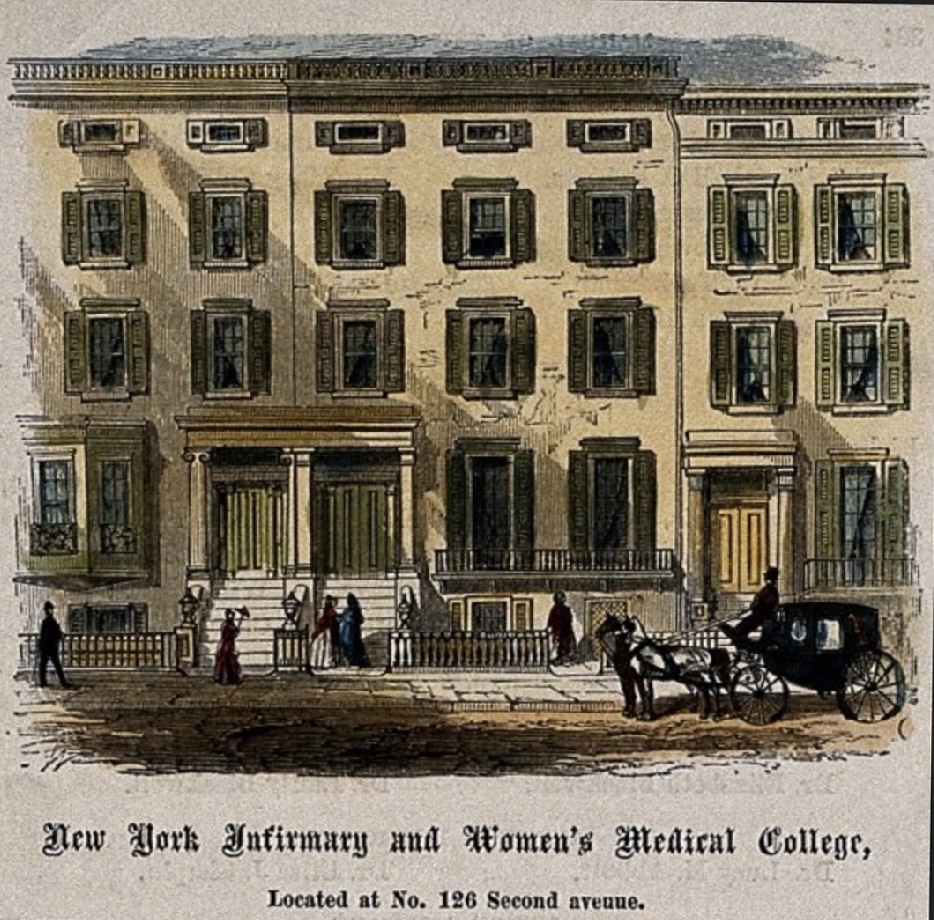

DRS. BLACKWELL AND COLLEAGUE FOUND THE NEW YORK INFIRMARY FOR WOMEN

Her younger sister Emily Blackwell completed her medical studies from (what is now ) Case Western Reserve University in 1854., becoming the third woman to earn a medical degree in the United States. In 1857, Elizabeth and Emily, along with colleague Dr. Marie Zakrzewska, founded the New York Infirmary for Women and Children and began giving lectures to female audiences on the importance of educating girls. It became the first hospital staffed entirely by women. Women served on the board of trustees, on the executive committee and as attending physicians. The institution accepted both in- and outpatients and served as a nurse’s training facility. The patient load doubled in the second year, and by 1866, nearly 7,000 patients were being treated per year.

THE CIVIL WAR PERIOD

In 1861, sympathized heavily with the North due to her abolitionist roots, and even went so far as to say she would have left the country if the North had compromised on the subject of slavery. Elizabeth and Emily joined with Mary Livermore to aid in nursing efforts by volunteering with the U.S. Sanitary Commission. Not surprisingly, they were met with some resistance on the part of the male-dominated organization. The male physicians refused to help with the nurse education plan if it involved the Blackwells. Still, the New York Infirmary managed to work with Dorothea Dix to train nurses for the Union effort.

THE WOMEN’S MEDICAL COLLEGE – A RADICAL INNOVATION

In 1868, Blackwell established a medical college for women adjunct to the infirmary. It incorporated her innovative ideas about medical education – a four-year training period with much more extensive clinical training than previously required.

ELIZABETH MAKES A PERMANENT MOVE TO ENGLAND AND RETIRES TO

A LIFETIME OF SOCIAL REFORM

A year after the Women’s Medical College was established, a rift occurred between Emily and Elizabeth Blackwell. Both were extremely headstrong, and a power struggle over the management of the infirmary and medical college ensued. Already feeling slightly alienated by the United States women’s medical movement, Elizabeth left her sister in charge of the infirmary and college, and in 1869 sailed for Britain to try to establish medical education for women there. The move was permanent and in 1875, she became a professor of gynecology at the new London School of Medicine for Women.

In the decades that followed, she diversified her interests, and was active both in social reform and authorship. She co-founded the National Health Society in 1871. Her greatest period of reform activity was after her retirement from the medical profession, from 1880 to 1895. Blackwell was interested in a great number of reform movements – mainly moral reform, sexual purity, hygiene and medical education, but also preventive medicine, sanitation, eugenics (!), family planning (note she was against contraceptives and argued for the “rhythm method” ), women’s rights, medical ethics and anti-vivisection. Her goal for reform – in any area – was based on evangelical moral perfection.

Blackwell had a very strong personality and was only interested in those organizations where she could be in charge, and thus was highly critical of many of the women’s reform and hospital organizations in which she played no role, calling some of them “quack auspices”.

AND THEN THERE WAS… KATHERINE “KITTY” BARRY BLACKWELL

c.1881 (age about 33)

(from Library of Congress)

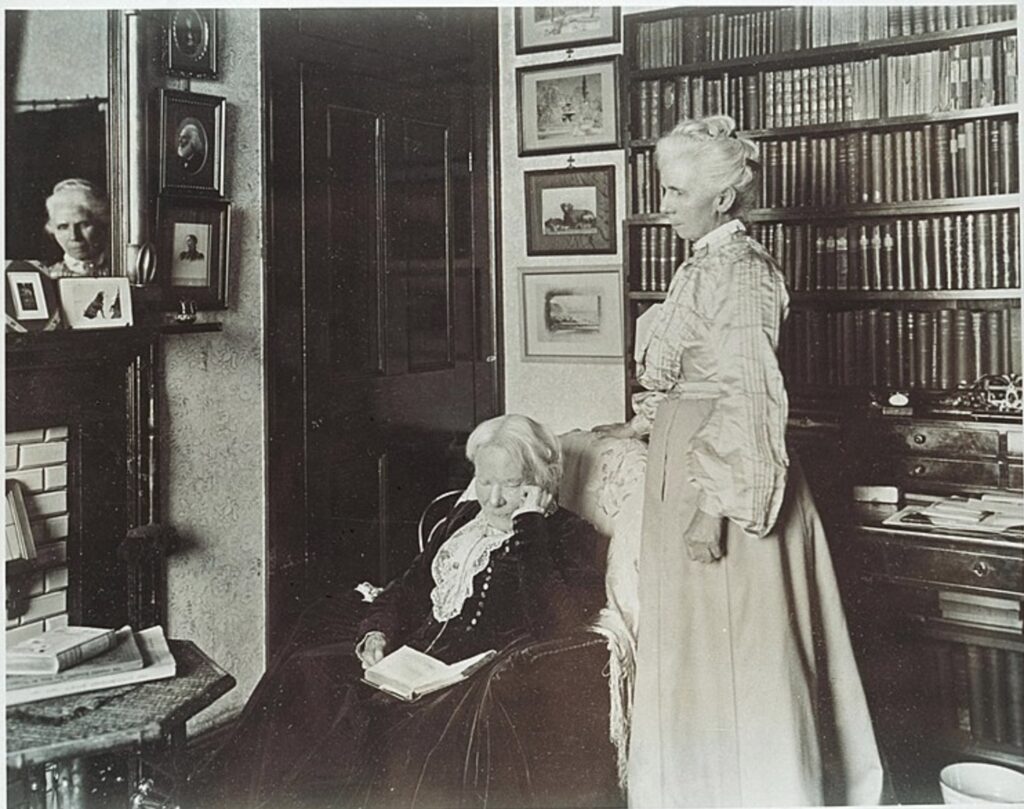

Elizabeth, along with all four of her sisters, never married. In 1856, when she was establishing the New York Infirmary, she adopted an 8 year-old Irish orphan named Katherine “Kitty” Barry from the House of Refuge on Randall’s Island. Diary entries at the time show that she adopted Barry half out of loneliness and a feeling of obligation, and half out of a utilitarian need for domestic help. Barry, who suffered from slight deafness, was raised as half-servant and half-daughter. Blackwell did provide for Barry’s education, but never permitted Barry to develop her own interests. While Barry herself was rather shy, awkward and self-conscious, Blackwell made no effort to introduce Barry to young men or women her own age In 1879, they moved into Rock House in Hastings, Sussex.

(Courtesy of Blackwell Family Papers, Schlesinger Library)

In 1907, while holidaying in Scotland, Blackwell fell down a flight of stairs, and was left almost completely mentally and physically disabled. On May 31, 1910, she died at Rock House after suffering a stroke that paralyzed half her body. Her ashes were buried in the graveyard of St. Munn’s Parish Church, Kilmun, Scotland. Barry moved to Scotland and in 1920, took the name Kitty Barry Blackwell. On her deathbed, in 1936, Barry called Blackwell her “true love”, and requested that her ashes be buried with those of Elizabeth.