TRAGICALLY KILLED IN THE EXPLOSION OF A CONFEDERATE POWDER MAGAZINE.

WITH PROVENANCE.

“BLOWN TO PIECES”

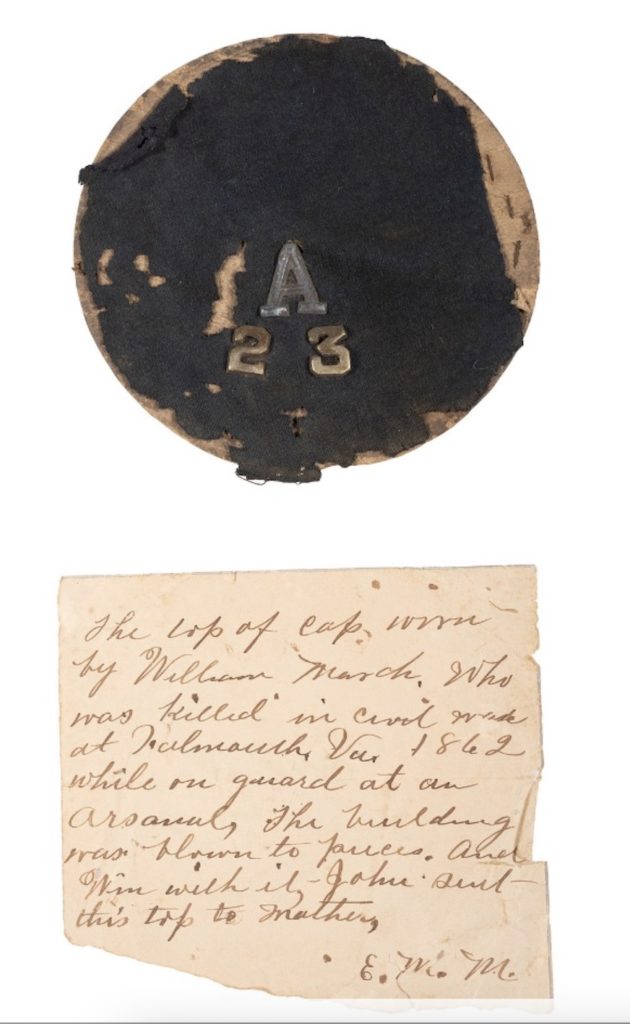

In a letter written on the Eve of St. Valentine’s Day, 1862, Pvt. John March of Co. A, 23rd New York Volunteers, assured his sister Alice, that their brother Bill, also of Co. A, was all right and would be home soon. Three months later, John sent to his mother virtually all that was left of her dead son, the torn and tattered remnant of the top of his forage cap, its unique company letter and regimental numerals still in place.

Some years later another sister, Effie March Murray, sat and penned the tragic history of this incredible relic:

“The top of cap worn by William March, who was killed in Civil War at Falmouth Va., 1862, while on guard at an Arsenal. The building was blown to pieces, and William with it. John sent this top to Mother.”

“E.E.M.”

The incident is further recounted and documented in the recently published book Banners South by Edmund Raus, Jr. On page 131 he writes:

Several frightened women came to their doors to ask passing Union staff officers if the Yankees intended to shell the town. Their fears increased when a tremendous explosion rocked the depot area about midmorning on the 25th…

…an accidental spark had ignited a munitions magazine in a detached brick building about 150 yards

from the train station. The blast destroyed the structure and shattered the glass in the adjacent buildings.

The sentry on duty, Southern Tier Private William March of Company A, had both legs torn from his body

from the explosion, which killed him instantly…”

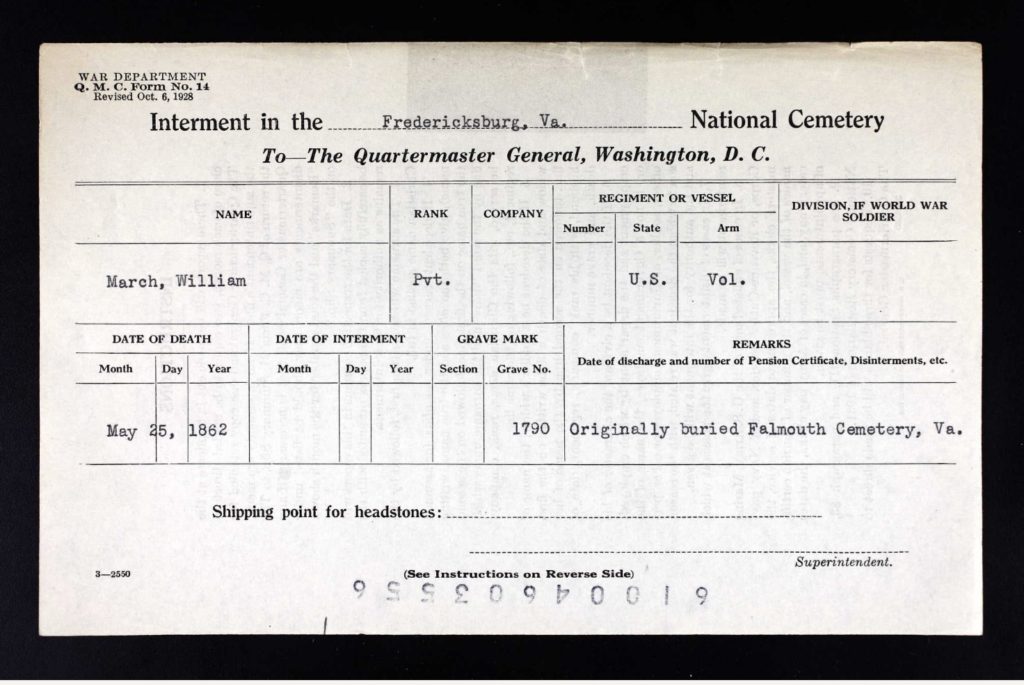

WILLIAM MARCH

1842 – 1862

The exact date of birth of William (known as “Bill” to his family) is not known. He was born in Danube (Herkimer county) New York about 1842, as one of nine children born to Peter Marsh and Nancy Gunoitte. His brother John was older by two years, and brother Byron was 2 years younger. His sister Alice was 5 years younger, and the baby of the family was Effie, born when William was 12. At some point after 1850, the family moved to Avoca, in Steuben county. Peter died in 1859, and left his widow and family with little means of support. In the 1860 census, William and his older brother Francis are each working as a “fireman”, and Nancy was earning money as a seamstress. Despite this, they were dreadfully poor. Their personal estate was valued at only 25 dollars, and she and the two younger girls are listed as “paupers”. A year and a half after William’s death, she filed a mother’s application for pension. She attested that she had been quite dependent on him for economic support prior to the war, stating that he furnished her with furniture, “all kinds of provisions sufficient for one third of the support of myself and children, and also furnished me with money at different times and that I have no means of my own wherewith to support myself and children.”

The family’s poverty may have been a driving force for the boys’ enlisting, aware that they would be receiving a small but steady pay to forward home. Whatever the reason, three of Nancy’s sons signed up after the conflict began: 19 year-old William was the first, enlisting as a Private in Company A of the 23rd New York Volunteers on April 30, 1861. Older brother John joined the Company in May. After he turned 18, their younger brother Byron joined in November of 1861, enlisting in Company K of the 104th New York Volunteers. Only one brother would be left after the war’s end.

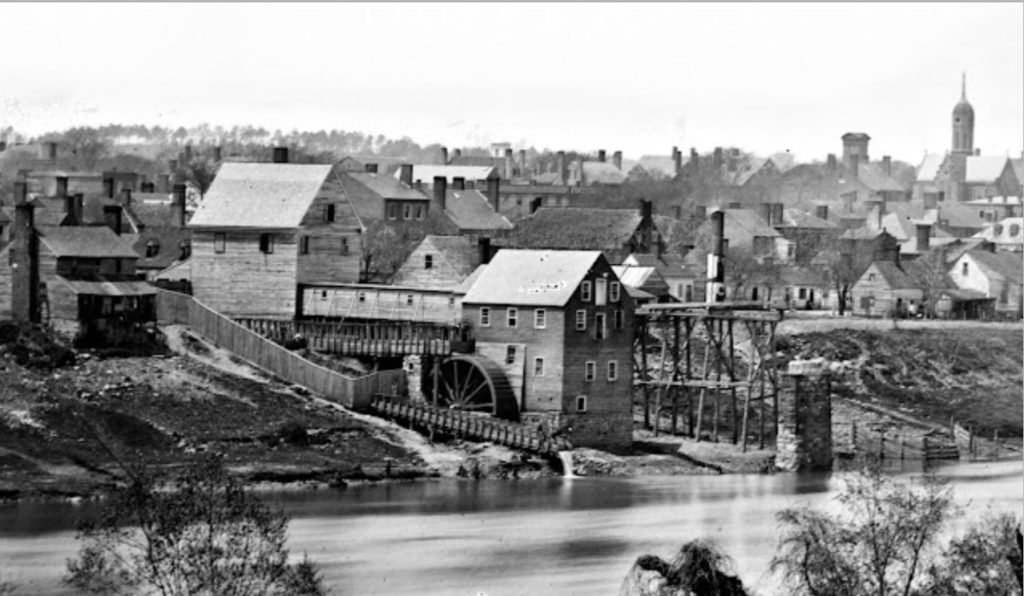

THE SETTING: FREDERICKSBURG, VIRGINIA IN 1862

(Destroyed Railroad Bridge on the Right)

150 years before the Civil War, pioneers recognized the importance of the Rappahannock River, and settled the town of Fredericksburg on its southern bank, in Spottsylvania county. A sister town called Falmouth sprang up across from Fredericksburg on the northern bank of the river, in Stafford county. The river fostered commerce and water-based industry, and by 1860, Fredericksburg had a population of about 5,000 (1/3 of which were slaves and free blacks.)

On April 18, 1862, Union Gen. Irvin McDowell’s army of 30,ooo occupied Falmouth. Upon their arrival, the retreating Confederates welcomed them by setting fire to military stores and the bridges over the Rappahannock on their way out of town. They dared not disturb their powder magazine, located in a brick building near the train depot in Fredericksburg.

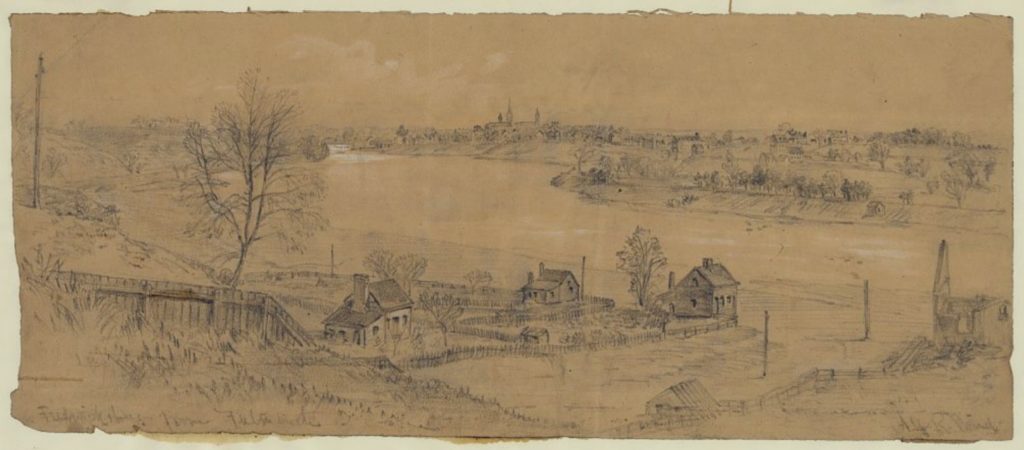

Sketch by Alfred Waud

Their retaliation succeeded in briefly interrupting McDowell, who had planned on using Fredericksburg as a springboard to begin an overland campaign in support of Maj.-Gen. George McClellan, then on the peninsula. They would meet outside of Richmond and if all went as planned, the jaws of their twin forces would slowly close on Richmond, sealing the fate of the Confederacy.

When the Civil War came, it did not go unnoticed from either side that from a military standpoint, Fredericksburg was a strategic location. The town was situated equidistant from Richmond, Va. (the capitol of the Confederacy) and Washington, D.C. and had control of the primary crossing point of the river. A telegraph line passed right through town. Jefferson Davis remarked that Fredericksburg stood “right in the wrong place”, and both the North and the South wanted control. But at its heart, it was a Southern town, and the sentiments of the vast majority of the populace lay firmly with the Confederacy. One citizen remarked, “A man is a fool who comes out for the Union in Fredericksburg.”

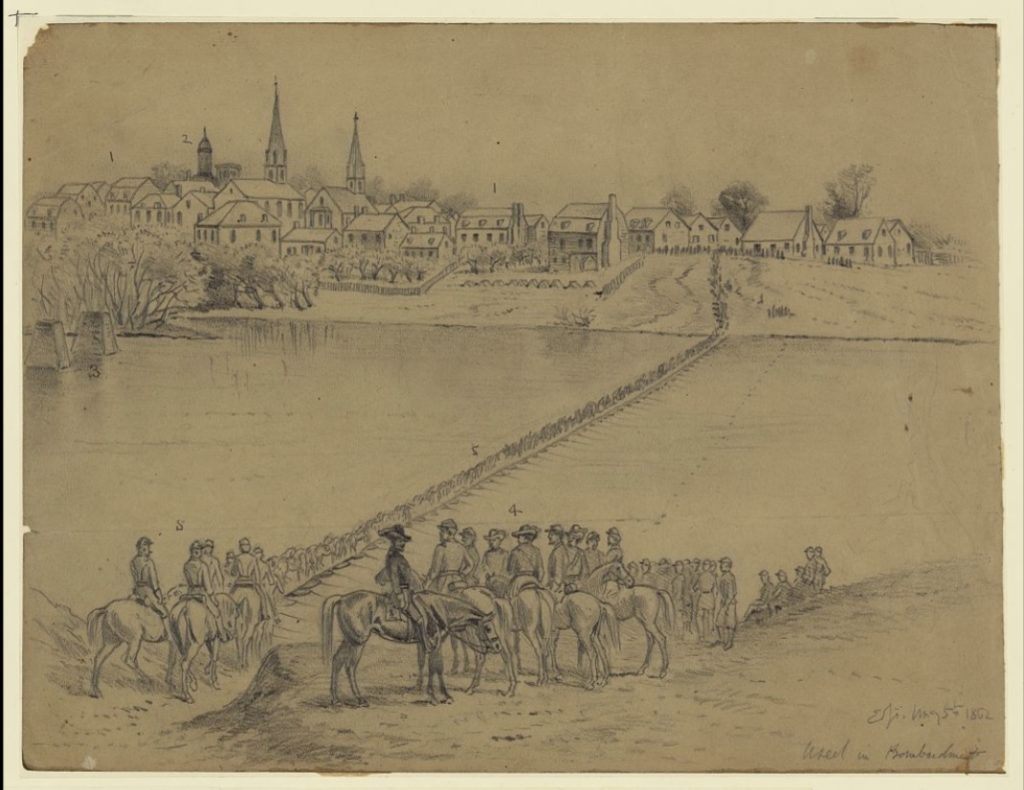

For now, the campaign was stalled in Falmouth until McDowell received the green light he was waiting for from Lincoln’s Secretary of War, Edwin Stanton, to occupy Fredericksburg. Having received it, there was still the matter of how to move a large body of troops (soldiers, supply wagons, animals and artillery) over a four-hundred foot span of water. The engineers were undaunted and by May 5th, they had erected a pontoon bridge across the river. Rebuilding the railway bridge, with its trestle, would take more time. (The Confederates would be repaid – in kind – when the bridges were destroyed by the departing Federals that August. )

Sketch by Edwin Forbes

Once the pontoon bridge was completed, General Marsena Patrick’s brigade was chosen to occupy Fredericksburg. Patrick would serve as Military Governor there. Col. Henry Hoffman’s 23rd New York Infantry, also known as the “Southern Tier regiment”, was chosen to be the first regiment to occupy the town (the remainder of the brigade would follow a few days later.) The 23rd crossed the river on May 7th, and Hoffman stationed companies in various areas around and within the town, securing its perimeter. Capt. Theodore Schlitz’s Company A was selected to guard the train depot.

The Union occupation briefly turned Fredericksburg into what could only be described (using modern jargon) as ”a hot mess.” Townspeople hurled insults, hissed at the soldiers in the streets, and spat at them from windows. Some boys threw rocks at the men. It was bad enough seeing the Union flag flying in town, but what was even more upsetting to the residents were the slaves who took advantage of the Federal occupation to put an end to their servitude. Once word was out that the Union Army occupied the town, slaves from plantations all over Spottsylvania county flocked to Fredericksburg. They sought the protection of the Union Army, and received it. Union guns trumped local law and permitted the slaves to walk among the (mostly white) townspeople, basking in their new-found freedom. For the first time, they could demand work that would pay wages. Believing that the black race was “ordained to serve the white man” (and perhaps out of fear of retaliation), Fredericksburg’s white population refused to hire them. The military was happy to employ them as guides, laborers, camp servants, cooks, or laborers to build the bridges, and paid them (albeit menial) wages. Some ex-slaves crossed the river to Falmouth and went on to their freedom farther north. By one estimate, 10,000 slaves secured their freedom during this time.

Both Gen. McDowell and Gen. Patrick (the latter known as a strict disciplinarian) became disgusted with the behavior of many of the soldiers and the lackadaisical attitude of their officers. Some Union soldiers were (in Marsena’s words), “plundering houses, insulting women and committing depredation for miles around”. McDowell was painfully aware of the rape of a young local girl by a Union straggler. It was so bad that Patrick referred to the troops as “a pack of Daemons.” His solution was to keep the men busy and on a short rein, but McDowell took it a step further. He instituted draconian measures and the power of summary judgement against any soldier who dared not toe the line, and ordered that rape and other serious offenses were punishable by hanging or if that were not convenient, the firing squad. It worked, and by mid-May, both soldiers and townspeople began to enjoy a much more peaceful coexistence.

On May 18, Patrick received word that a Union reconnaissance a few miles out of town had run into Confederate pickets and stirred up trouble. He gathered several regiments and rode out to meet them, deploying Companies A and K of the 23rd New York as skirmishers. Seeing the show of force, a few shots were fired before the Rebels skedaddled.

By May 19, the railway bridge was completed, the first locomotive chugged along its span, and the connection between McDowell’s supply base and Fredericksburg was established.

On the morning of May 23rd, in ninety-degree heat, President Lincoln arrived in Falmouth to confer with General McDowell and give the troops a formal send-off. In the evening he crossed the river to Fredericksburg and, escorted by General Patrick, took a carriage ride through town. Later that night, when Lincoln returned to Falmouth, he reviewed troop positions and recent developments with McDowell, advising him to sit tight and start his campaign on May 26th.

Although we are not privy to the details, John March, William’s older brother had just been reduced in rank from Sergeant to Private two days earlier, as ordered by the authorities (or perhaps a court-martial) as punishment for a military infraction.

Such was the state of affairs when 2 days after Lincoln’s visit, an explosion near the train depot rocked the area.

THE EXPLOSION

According to the Alexandria Gazette, the weather on May 25, 1862 was “cooler” than it had been. That afternoon, Gen. Patrick’s brigade was going to leave Fredericksburg and start in the supposed direction of General Stonewall Jackson’s troops. He was going to take three regiments with him, and send the 23rd along the river to protect his flank.

The soldiers of the 23rd were for the moment, still encamped in the area of the train depot where they had been stationed since arriving in Fredericksburg two weeks earlier. Apart from the excitement of a week earlier when they came near to engaging enemy troops, the brouhaha of the first two weeks of May had disappeared. Emotions on both sides had cooled down, and the town was deadly quiet. They were beginning to rebel against the waste of their time marching in circles or standing sentry over Southern property. Having seen little action since enlistment, many felt excited at the prospect of finally experiencing combat.

Then the explosion happened.

A small paragraph on page 3 of the May 27th edition of the Alexandria Gazette tersely records the event:

“An explosion took place in Fredericksburg, Va. about noon on Sunday, in a brick building which had been used by the rebels as a powder magazine, killing the sentinel on duty and destroying the building but doing no further damage. Some grape-shot, which were laying on the kegs of powder, were thrown a great distance – clear across the river. The explosion is not accounted for.”

The blast destroyed the structure and shattered the glass in the adjacent buildings. The “sentinel on duty” was 20 year old William March, Private in Company A, 23rd New York Volunteers.

John surely realized that the explosion came from the direction of the powder magazine, and perhaps his heart sank from a sense of foreboding. He joined the others who ran to the scene, ears still ringing from the noise. The smell of sulfur permeated the air, and burning fumes stung their eyes and nostrils. Soldiers covered their noses and mouths with their hands, or arms, or perhaps a neckerchief. An enormous cloud of smoke rose from the area where only seconds before, a brick powder magazine had stood. Now there was only rubble everywhere; splintered wood and shrapnel lay among brick fragments no larger than one’s hand.

They found what was left of William March, and it wasn’t much. Chunks of bloody tissue, some with clothing attached, were scattered over an area of the ruins, presumably where he had been standing at the time of the blast. His head and torso were mangled, and both legs were gone. There was nothing to identify who he had been, apart from the knowledge that Pvt. William March of their company had been assigned as sentry. That much was confirmed when they found the only part of his uniform that had remained in one piece – and John recognized it immediately. It was the top of his forage cap, with the company letter and regimental numeral still intact.

EPILOGUE

Over the next few days, John penned a letter to his mother informing her of his death. He enclosed it in a small package containing the only part of William that remained, the top of his cap. He did not give her the details of the condition of William’s body; she would draw her own conclusions from his explanation of how his death occurred.

Their brigade left as planned that afternoon, crossing the river to Falmouth and taking most of what was left of William with them. He was hastily interred in a grave there.

The following month, the 23rd left the Army of the Potomac and finally got their taste of battle. They shared in General Pope’s campaign on the peninsula, participating in Gaines Mill and the Second Bull Run. In September, it rejoined the Army of the Potomac and participated in the battles at South Mountain and Antietam. They returned to Fredericksburg in December, and was closely engaged at the Battle there. On May 22, 1863, almost one year exactly from the date of William’s death, the regiment was mustered out at Elmira, New York.

John re-enlisted in the 22nd New York Cavalry in early 1864, and was at the battle of the Wilderness, Sheridan’s Valley Campaign, Spottsylvania, and Cold Harbor. He was the only one of the three brothers to survive the war. Their younger brother Byron, who had just veteranized in the 104th New York Volunteers in January 1864, was sent home to Avoca with “liver disease”, and died there a month later on February 29th.

In 1865, the government established the Fredericksburg National Cemetery for the over 15,000 Union soldiers who had died in the area. The identities of fewer than 3,000 are known. William’s remains were moved from Falmouth and were re-interred there in grave #1790, sometime between 1866 and 1869.

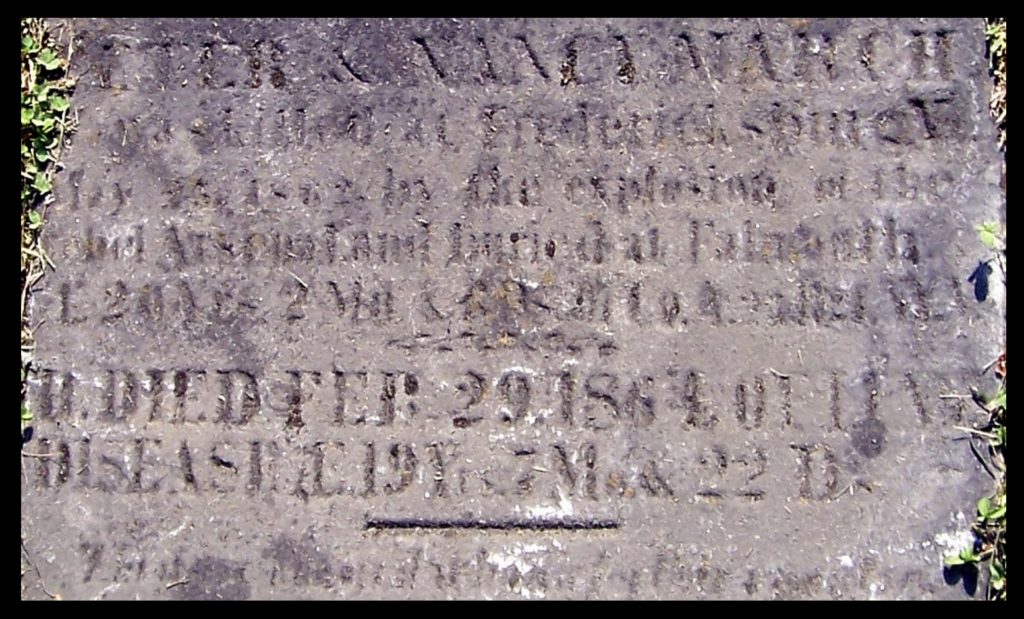

Byron March was interred in Old Avoca Village Cemetery in Steuben county, New York. He shares his gravestone with William, whose death is memorialized there – though he remains still lie in Virginia:

“WILLIAM & BYRON”

SONS OF

PETER & NANCY MARCH

W. was killed at Fredericksburg Va

May 25 1862 by the explosion of the

Rebel Arsenal and buried in Falmouth

AE 20 Yrs 2 Mo. & 6 D Co. A 23rd N.Y.V.

B. DIED FEB. 29, 1864 OF LIVER

DISEASE AE 19 YRS 7 Mo. & 22 Dy