INTRODUCTION TO PRE-WAR COLLECTIBLES

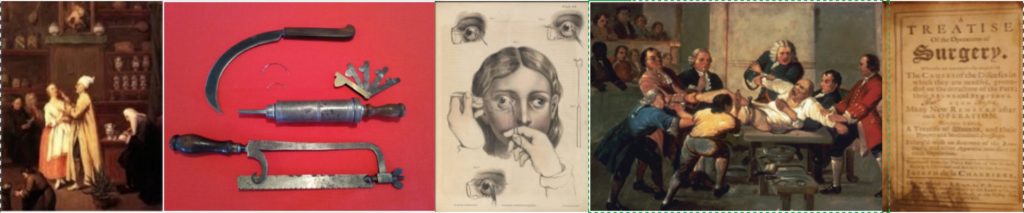

I have divided the category of Pre-War Amputation and Surgical Sets in three sub-groups: Pre-Civil War Cased Amputation & Surgical Sets, Pre-Civil War Trepanning or Trephining Instruments and Sets, and Pre-War Pocket Surgical Sets. As noted above, “Pre-War” refers to Pre-Civil War. The items in this category date from the mid- 1700’s and end in the mid-19th century, roughly 1859. As you will see, many of the earliest items originate from the United Kingdom, chiefly London, England (and surrounds) and a few from Edinburgh, Scotland. Surgery in the United Kingdom has been practiced for nearly 2000 years, and obviously much later in the American Colonies; medical and surgical items made in America during the 18th century (and even into the early 19th century) are exceedingly rare. I include a digression on the other “pre-war” periods of surgery for educational purposes.

(ANCIENT) PRE-WAR

There is evidence that trepanation (also called trephination), was performed in Northern Africa as far back as 10,000 BCE. Skulls in France dating to 6500 BCE have also been found with evidence of rudimentary trepanation. Traditionally, wars have been the proving ground of surgeons and new types of surgery, and led to developments in surgical procedures dating from 1750 BCE to 950 BCE in such cultures as Babylonia, Egypt, India and Arabia. The Greeks and Romans practiced surgery, but believed it should be used as a last resort. Homer’s Iliad, compiled around 800 BCE, remains the oldest record of Greek medicine and a unique source of surgical history – particularly battlefield surgery, the forerunner to modern trauma surgery.

(COLONIAL) PRE-WAR

In early colonial times the word “physician” did not imply the precise definition we accept today. Some practitioners were educated, some not. Some were ministers. Only a few had earned M.D. degrees at European medical schools. Steeped in the Puritan ethic, and in an absolute belief in the supernatural and a fierce and unforgiving God, the minister-doctor combination is exemplified by Boston’s Cotton Mather (born 1663), who portrayed the two professions in “an angelic conjunction.” The author of a 1953 article for the “American Antiquarian Society” called Mather the “First Significant Figure in American Medicine”. Although Mather had studied both the ministry and science & medicine while in college, his first choice was the Church, the second medicine. Interestingly, Mather’s “angelic conjunction” allowed him to juxtapose his belief in witchcraft & spectral evidence with his belief in the necessity of smallpox inoculation. Mather was in the habit of prescribing to locals, and frequently inserted medical comments while recording the last illnesses and deaths of those in his flock. He viewed extraordinary episodes of healing through the lens of divine providence: “Abigail Eliot lost part of her brain in an accident. Those which remained thereafter swelled with tides. Yet with insertion of a silver plate in her head, she lived happily ever after.” Although he ascribed this medical miracle to God, he dutifully notes the names of the “able chyrurgeons” Messrs. Oliver and Plat whose hands channeled the divine miracle. After examining the child (her skull had been accidentally pierced by a sharp piece of iron), they pushed the extruded brains back into the cranium through the “half-crown sized” opening, and inserted a silver plate to keep all in place. She lived to be the mother of two children, “not defective in memory nor understanding.” Fortunately, she did not suffer from seizures following the injury or Rev. Mather might have accused her of being a witch, “divine miracle” notwithstanding.

Some seventy-odd years later, there were approximately 3,500 practicing physicians in the colonies. Most had more in common with a medieval barber than a modern M.D. Some had been trained at European schools, others at the first medical college to be opened in America, the Pennsylvania Hospital, which opened in Philadelphia in 1768. Two years later, Kings College opened in New York. As was the case for centuries, the Revolutionary War spurred innovative thought and advances in medicine and surgery. Doctors observed more in one day of battle than they could have in years of peacetime. The result was a burgeoning of medical education and colleges, and of physicians and surgeons who undertook medicine as a profession.