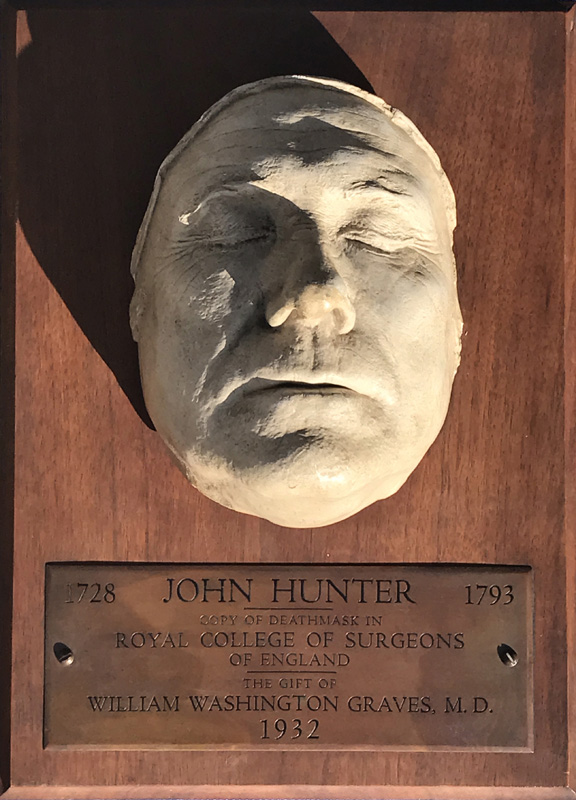

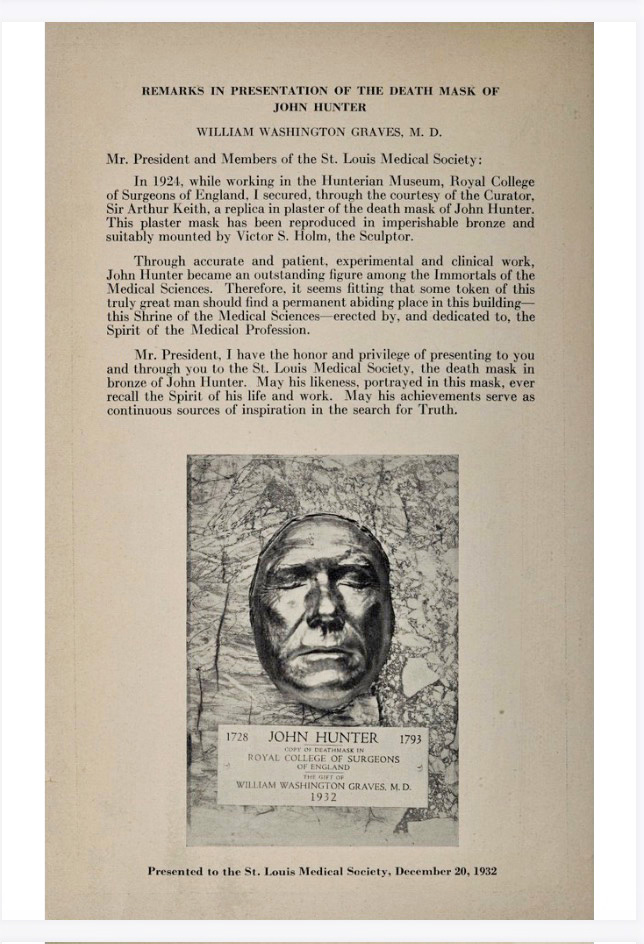

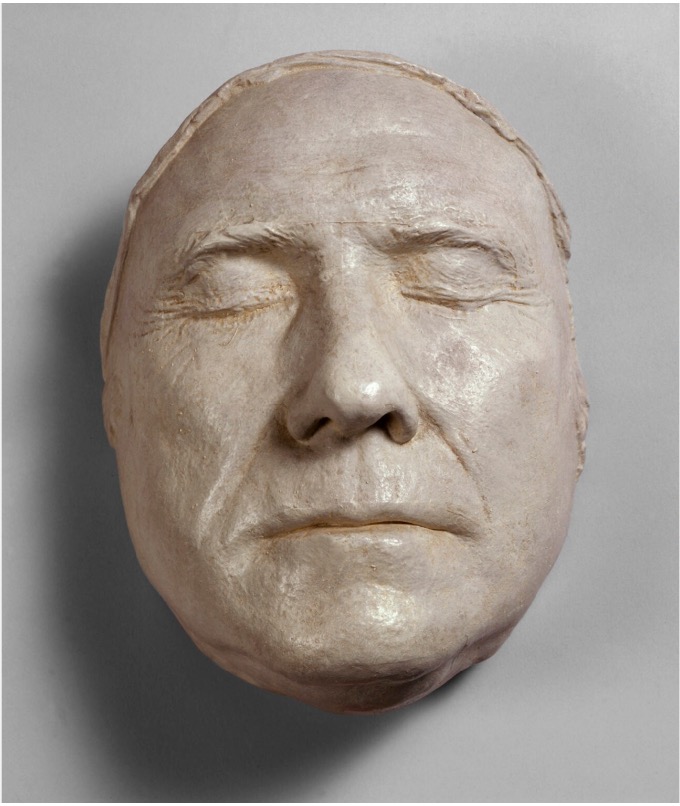

This very rare item is a first-generation copy of the original death mask of John Hunter, which is housed at the Royal College of Surgeons of England. John Hunter (1728 – 1793) was a Scottish surgeon, one of the most distinguished scientists and surgeons of his day. The detail is superb, and my research indicates that it is indeed a first-generation copy of the original mask. This plaster cast of the original mask was made in 1924, by Sir Arthur Keith, then curator of the Hunterian Museum in the Royal College of Surgeons in England. It was made at the request of William Washington Graves, M.D., an American physician who was working at the museum. In 1932, Dr. Graves commissioned Victor S. Holm, a Danish-born sculptor working in the St. Louis Artist Guild, to cast a bronze mask from the plaster one he was given by Sir Keith. The cast-bronze mask was mounted on a marble base and presented to the St. Louis Medical Society. The plaque on that presentation piece is identical on the one shown above. It would appear that Dr. Graves donated the bronze version, but kept the plaster copy that Sir Keith made for himself, and had it mounted (albeit on wood rather than marble) with the same plaque. A small pamphlet was printed to honor the occasion of Dr. Graves’ donation. It is held in the Wellcome Collection in London, and select pages from it are shown below:

The National Portrait Gallery in London has a similar item; a photo and description follows:

“John Hunter – by Unknown artist – plaster cast of life mask, 1913 or before, based on a work of circa 1785.

8 1/2 in. diameter. Given by Domenico Brucciani, 1913.”

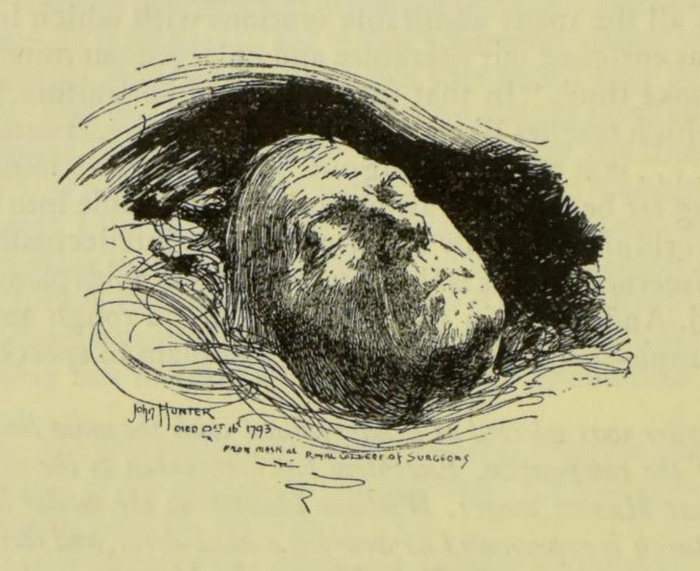

In a small book written in 1901, a treatise on a painting titled “John Hunter Leaves St. George’s Hospital, October 16, 1793” (the date of his death), the tailpiece of the book shows “a drawing of the death mask in the Royal College of Surgeons.”

JOHN HUNTER, M.D.

1728 – 1793

Hunter, born in Glasgow, was an early advocate of careful observation and scientific method in medicine. He was a teacher of, friend of, and collaborator with, Edward Jenner, the inventor of the smallpox vaccine.

He learned anatomy by assisting his elder brother William with dissections in William’s anatomy school in (South) London, starting in 1748, and quickly became expert in anatomy. He spent some years as an Army surgeon, worked with the dentist James Spence conducting tooth transplants, and in 1764 set up his own anatomy school in London. He built up a collection of living animals whose skeletons and other organs he prepared as anatomical specimens, eventually amassing nearly 14,000 preparations demonstrating the anatomy of humans and other vertebrates. In 1783 Hunter moved to a large house in Leicester Square, where today there stands a statue to him. The space allowed him to arrange his collection of nearly 14,000 preparations of over 500 species of plants and animals into a teaching museum.

It is possible that his Leicester Square house was the inspiration for the home of Dr. Jekyll of the Robert Louis Stevenson novel The Strange Case of Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde. Hunter’s house had two entrances, one through which the living area for his family was accessible, and another, leading to a separate street, which provided access to his museum and dissecting rooms. This pattern echoes that of the house in the story, in which the respectable Dr. Jekyll used one entrance to the house and Mr. Hyde the other, less prominent, one. He was described by one of his assistants late in his life as a man ‘warm and impatient, readily provoked, and when irritated, not easily soothed’. Hunter’s character has been discussed by biographers:

“His nature was kindly and generous, though outwardly rude and repelling…. Later in life, for some private or personal reason, he picked a quarrel with the brother who had formed him and made a man of him, basing the dissension upon a quibble about priority unworthy of so great an investigator. Yet three years later, he lived to mourn this brother’s death in tears.”

CHARLES BYRNE

1761 – 1783

“THE IRISH GIANT”

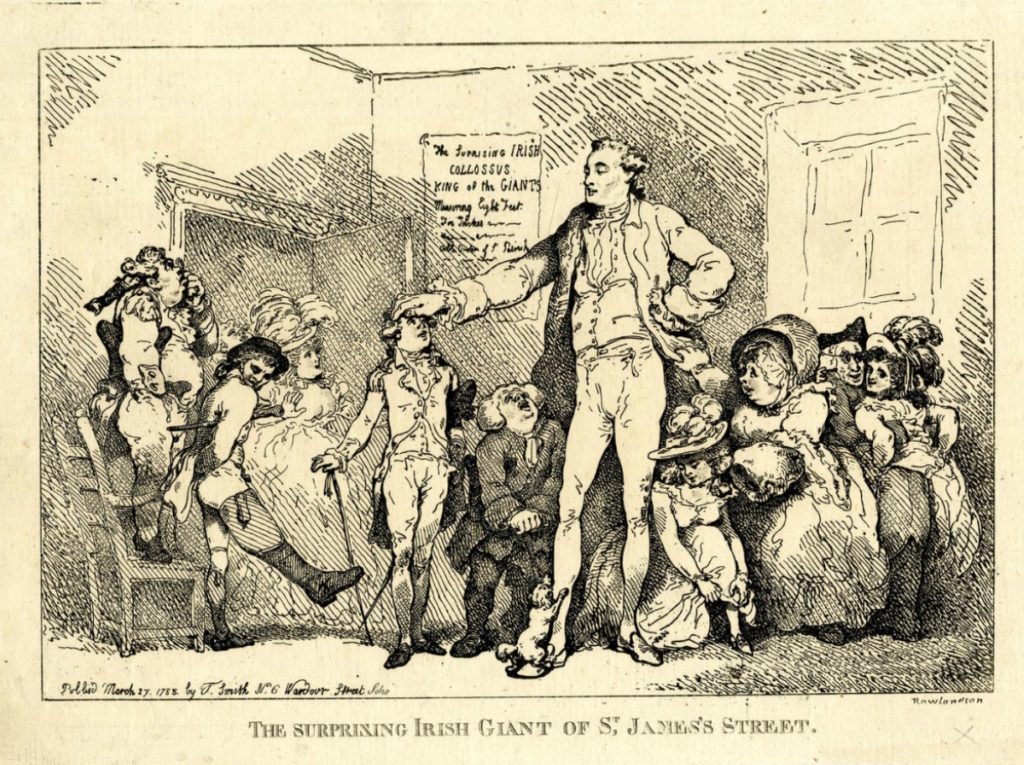

Charles Byrne was an 18th century Irishman of extraordinary stature who became famous as “the Irish Giant” in London’s Cox’s Museum (a sideshow/museum of oddities similar to P.T. Barnum’s American Museum in New York City). Born in 1761, Byrne was already abnormally tall in childhood, and by the time he was a teenager his height had made him a popular local sideshow attraction. His 7’7″ height resulted in rumors that he was so tall that he could light his pipe from a street lamp. When he was 21, he left Ireland to seek fame and fortune in London. During his short life he became famous and wealthy, and was received by the King and Queen and the Duke and Duchess of Devonshire.

Unfortunately, Byrne’s “career” was a short-lived success. Under the strain of his deteriorating health and the pressures of celebrity, barely more than a year after his move to London, the Irish Giant drank himself to death. After a lifetime spent on display, Byrne’s deepest fear was that his body would be stolen by “resurrection men” in the employ of eminent Scottish anatomist John Hunter who was famous for his collection of anatomical specimens and oddities. Byrne told his friends that when he died he wanted to be sealed in a lead coffin and buried at sea to avoid this horror. One of those friends turned coat in the most despicable way: he became the resurrection man Byrne feared. Hunter paid him 500 pounds (almost $80,000 in today’s money) to remove the body from the coffin while the funeral party was in a pub on their way to the English Channel. He placed paving stones in the casket and gave Hunter his friend’s body.

Hunter boiled it immediately, probably in fear of imminent discovery, and hid the skeleton for four years. Once he figured the coast was clear, he put the giant’s skeleton on display in his museum. After Hunter’s death, his collection was bought by the British government and became the core of the Hunterian Museum at the Royal College of Surgeons in London which to this day has Charles Byrne’s body on display.

In 1909, a surgeon name Harvey Cushing studied Byrne’s skeletal remains and found the cause of his gigantism. Gigantism is caused by an over-production of growth hormone in childhood resulting in excessive growth and height significantly above average (between 7 feet and 9 feet tall).

Cushing found that the area where the pituitary gland rests, the pituitary (or the hypophyseal fossa of the sphenoid) was enlarged in Byrne’s skull. In 2011, British and German researchers extracted DNA from Byrne’s teeth and found that he had a rare genetic mutation, only discovered in 2006, that causes pituitary tumors, confirming Cushings earlier findings.

Hunter became a Fellow of the Royal Society in 1767 following a heart attack during a heated argument at St. George’s Hospital over the admission of students.

WILLIAM WASHINGTON GRAVES, M.D.

1865 – 1949

Dr. Graves was a physician and neuroscientist and lived in St. Louis, Missouri. He was born in Kentucky, his mother being a direct descendant of Davy Crockett. His family moved to Missouri a few years after his birth. He studied medicine at the St. Louis College of Physicians and Surgeons, and graduated in 1888. He became a prominent and successful physician in St. Louis. Unfortunately, this did not mean that his theories were always legitimate.

The May 1938 edition of “Modern Mechanix” magazine’s headline read “Your Shoulder Blades Predict How Old You’ll Be”. This “discovery” was made by none other than Dr. Graves, who had published that “persons having the convex-type of shoulder blades have a better chance in life than those who have straight or concave scapulae, and those with a mixed combination of types fare more poorly in life than the ones who have both blades either convex or concave.” For his contributions to science, in 1939 Graves was awarded a Certificate Of Merit from the St. Louis Medical Society, something “The Eugenics Review” magazine called an “outstanding event.” In presenting the Certificate, his colleagues heaped laudatory comments praising his work in “the inherited qualities of human constitution, expressed in inherited predisposition to health or disease, and in inherited capacity for education, for adaptability, and for longevity.”

In a pamphlet accompanying the ceremony, it is noted that “A copy of the death mask of Dr. John Hunter, the original of which is in the home of the Royal College of Surgeons in London, is another of his contributions. This mask is to be found on the wall of the Bartscher Room.”

That mask and plaque is a bronze casting of the one shown above.