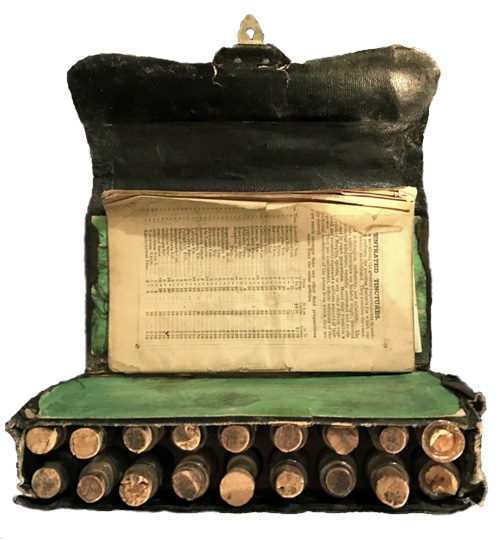

CONTAINING 18 VIALS WITH ORIGINAL “CONCENTRATED MEDICINE” CONTENTS, AND PAMPHLET FOR USE.

MANUFACTURED BY “B. KEITH” OF THE “AMERICAN CHEMICAL INSTITUTE.”

THE “AMERICAN CHEMICAL INSTITUTE”

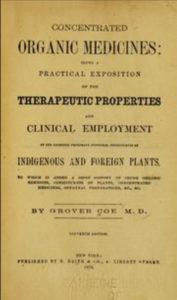

A follower of Thompsonian Medicine (an alternative system of medicine based on herbalism and botany), B. Keith of New Hampshire was a “physician” and entrepreneur who jumped on the bandwagon of eclectic medicine, going to New York in the 1850’s where he began manufacturing “concentrated medicines.” He hired Dr. Grover Coe, a former president of the National Eclectic Medical Association, to be his public relations man, and B. Keith & Co. became the “American Chemical Institute”

The stated object of the Institute was “to prepare the active principles of Indigenous and Foreign Medical Plants… All of the articles manufactured at our laboratory will be put up in vials of flint glass, be hermetically sealed, and stamped American Chemical Institute, N.Y.” No less than 14 wholesale agents were listed as distributors. A prominent Cincinnati pharmacist named Edward S. Wayne made a chemical analysis of Keith’s preparations and found that many of them were “fraudulently adulterated with magnesium carbonate, iron salts, sodium chloride and tannic acid.” By the Civil War, eclectic practitioners were disillusioned with concentrated medicines as they realized that the vast majority of these products were worthless and inert.

DR. BETHUEL KEITH (1811 – 1884 )

Bethuel Keith was born about 1812 in Randolph, Orange County Vermont. In 1844, he is listed in the New Hampshire Annual Register as practicing medicine in Dover, a member of the “Botanic” school of practice. In the 1850 census, he is living in Dover, Strafford county, New Hampshire. His age is 38, and his occupation is given as “physician”. He heads a household of nine others, including three minor children and one George H. Keith, who is listed as a Dentist. One physician from the area recalled working with Dr. Keith in 1846:

“I went to Dover, N. H., where I engaged with Dr. Bethuel Keith for the study of medicine. Dr. Keith kept, at that time, a small private hospital in connection with his general practice, and the situation thus afforded a fine opportunity for observation and some practice. In the fall of 1847 I went with Dr. Keith to Cincinnati, Ohio, to attend a course of lectures; passing the whole winter. The engagement with Dr. Keith was terminated in the spring of 1849…”

Dr. Keith moved to New York City about 1857, at which time he is listed in the New York City directory as “B. Keith & Co., manuf. active principles foreign and indigenous plants”. In the 1860 census, he is listed as a “physician” with a personal estate of $1000. He lives with his wife Elizabeth and four children, along with a dressmaker, tailor and servant. He is found in the New York City directories up until 1879, at which time he resided at 41 Liberty Street, with his business still listed as “B. Keith & Co.” Evidently, his sales were lucrative enough that he was able to retire to Jacksonville, Florida starting in 1880.

It is interesting to note that he does not appear in the AMA deceased physician database, which confirms that like many of the alternative practitioners of the time, he did not follow the medical curriculum of “regular”, or allopathic physicians, so was not eligible for the degree of Medical Doctor.

Keith was largely self-taught, evidenced by his son’s recollections. Nathaniel Shepard Keith was born in 1838, and became an inventor, manufacturer, chemist, and electrical engineer. He recalled learning the basics of chemistry in the laboratory of his father, Bethuel Keith & Co. The younger Keith attended New York University Medical School but never practiced medicine. Instead he became a respected chemist and electrical engineer, and was responsible for installing the original electrical lighting and power system in San Francisco, California. He returned to the East Coast in 1870 and had patents on a metallurgical process as well as early electric lights and motors. Heading West again, he built the first electric plant in San Francisco and served as a consultant to mining companies, being among the first to apply electricity to mining. After spending four years in England trying to promote an electro-metallurgic process to extract precious metals from their ores, he returned to the US and became an advisor to Thomas Edison.

ECLECTIC MEDICINE AND “CONCENTRATED MEDICINES”

During the first half of the 19th century in America, a branch of medical philosophy that came to be known as “eclecticism” took root. The term “eclectic” meant that the practitioners integrated whatever worked – botanicals, homeopathy, hydropathy, Native American herbal medicine – to treat the patient. Traditional medical practitioners of the era, who called themselves “regular” doctors, or allopaths, employed standard medical practices of the time which made extensive use of purges with calomel and other mercury-based remedies, as well as extensive bloodletting. Homeopathic physicians used infinitesimal doses medications to “treat like with like”. Eclectic medicine sought a road down the middle of these two dominant practices. The Eclectic Medical Institute in Worthington (and later Cincinnati), Ohio, graduated its first class in 1833. Throughout the 1840’s, eclectic medicine expanded as part of a large, populist, anti-regular medical movement in North America, which paralleled the politics of the era. Jacksonian Democracy, rooted in individualism, help spur a backlash to the “regular” physicians of the time, whose costly fees and dangerous remedies often yielded dismal results. Eclecticism was a direct reaction to the barbaric practices of the regulars, and made its strongest bid for scientific recognition by developing a distinctive pharmacy of indigenous plant remedies.

In 1835, John King, who was called by author John S. Haller “the analytical pharmacologist of eclectic medicine”, distilled out the resin of the plant Podophyllum, and began prescribing it (Podophyllin) as a substitute for calomel. He subsequently developed resins from other plants, such as Macrotin from macrotys (Cimicifuga racemosa), and oleoresins from others: Irisin (iris) and Leptandrin (leptandra, or Culver’s root). The resins and oleoresins that King developed were stable and active concentrated forms of the plants from which they were derived. These concentrated medicines (resins and oleoresins) represented the therapeutic effect of the whole plant; so only a small amount was needed, as it could be reconstituted with water, alcohol or syrup to make a therapeutic dose. In 1847, William S. Merrell of the Union Drug Store in Cincinnati prepared Podophyllin for commercial use. He recognized that the bulky and nauseating medications carried by physicians could be replaced by small vials of medications, which fit nicely in a saddlebag, and that could be made palatable – and the market for these “concentrated medicines” loomed large. By 1853, Merrell offered resinoids and oleoresins made from a wide variety of plants. While many of these had not undergone sufficient investigation as to their medicinal value, clever marketing to allopaths and country doctors created a lucrative industry, as physicians jumped onto the “concentrated medicine” bandwagon. In 1855, King, appalled at the promulgation of these untested preparations, wrote a scathing criticism of concentrated medicines in which he condemned them as a “stupendous fraud” and quackery, fearing they would tarnish the cause of eclecticism. Sadly, this did nothing to stem the burgeoning industry.

It was Merrell’s success that spurred B. Keith to begin his American Chemical Institute, which manufactured products with little (if any) quality control. Dr. Wayne’s findings that not only were many of the chemicals not pure – some were adulterated with household chemicals – resulted in a public diatribe between him and B. Keith, each accusing the other of making fraudulent statements. Seeing that greedy enterprise had tainted his achievements, King headed a faction of eclectic practitioners in alerting both eclectic and allopathic physicians to the dangers of the adulterated concentrated medicines that were flooding the mass market. A crusade of disfavor continued with repeated attacks, chiefly now from within the school to which they owed their origin. An editorial written by the conspicuous Eclectic authority, Professor John M. Scudder, M. D., is an example:

“In 1855 much of Eclectic medicine was an unmitigated humbug. That was the day of the so-called concentrated medicines, and anything having a termination in “in” was lauded to the skies. It was claimed that these resinoids were the active principles of the plants, and as they would replace the old drugging with crude remedies and teas, they must prove a great boon. But they did not give success, and finally, after trying them for awhile, the practitioner would go back to the crude articles and old syrups and teas with success, or he would settle down to podophyllin catharsis and quinine.”—Editorial by John M. Scudder, M. D., Eclectic Medical Journal, March, 1870.

Sales dropped, and the market for concentrated medicines was essentially gone by the start of the Civil War.